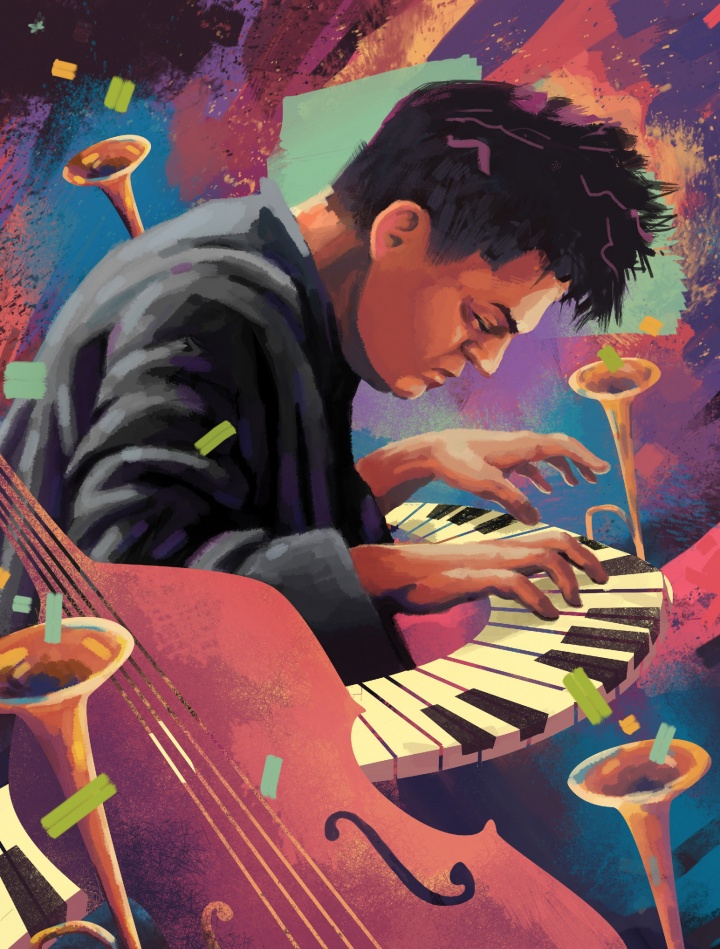

Irreverent and energetic, composer Nico Muhly ’03 is turning the classical world on its ear.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Irreverent and energetic, composer Nico Muhly ’03 is turning the classical world on its ear.

There’s a delicious scene in the third season of Amazon’s Mozart in the Jungle in which Nico Muhly ’03, Juilliard’04, playing himself, introduces an aria he has composed expressly for La Fiamma, a Maria Callas-style prima donna portrayed by Italian actress Monica Bellucci. He demonstrates her singing part on a grand piano in her Venetian parlor, explaining that the piece will also feature pre-recorded sounds and fragments of text that she will sing into a microphone and then repeat using a foot pedal. Before the proud La Fiamma will agree to this departure from her standard repertoire, however, she needs some convincing. “What is the story about?” she asks.

“The character is a young American woman named Amy Fisher,” Muhly tells her. “She’s having an affair with an older man, and she goes over to his house and shoots his wife in the head. His name is Joey Buttafuoco.”

He pronounces it the American way, the way newscasters did when the “Long Island Lolita” made sensational headlines in the early ’90s: Buttah-fewco. La Fiamma corrects him. “Boota-fwocko,” she says.

If this were an old-school sitcom, the laugh track would kick in right about here. But while Mozart in the Jungle is fun, it takes music seriously enough not to waste a cameo by the world-renowned Muhly, who in his 20s became the youngest composer ever commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera. So we’re treated to a glimpse of the real Nico: artistically adventurous, charming and sensitive to the hopes and agonies of Fisher or anyone else whose private passions lead to public tragedy.

“Fisher’s world is really intense,” Muhly reflects in his West 37th Street music studio in Manhattan. “Like Romeo and Juliet, she’s in this highly charged erotic and emotional situation — only it isn’t in a glamorous place. It isn’t Verona; it’s Massapequa. But I don’t like this idea of high versus low [culture], because it’s really just people.”

Muhly often turns to such real-life dramas in his works. His first opera, Two Boys, which had its Met premiere in 2013, was inspired by the fatal stabbing of a Manchester, England, youth by a lover he had met in an Internet chat room. His song cycle, Sentences, contemplates the life of Alan Turing, the pioneering British computer scientist who cracked top-secret German codes during WWII and was subsequently prosecuted as a homosexual. A second opera, Dark Sisters, springs from the story of a fundamentalist, polygamous Mormon community in Texas whose children were removed by state officials concerned about child abuse.

Even before his Met commission, Muhly had impressed the classical music world with his sensibility and originality. As early as 2004, New Yorker critic Alex Ross had flagged the “spiky-haired, healthily irreverent” Muhly, still studying at Juilliard,as “poised for a major career.” Ross presciently wrote: “If Muhly simply dumped his diverse musical loves into a score, he would have an eclectic mess. Instead, he lets himself be guided by them, sometimes almost subliminally.” In a short piece performed at the conservatory, “he asks players to be ‘spastic,’ to ‘smudge’ certain notes, to ‘ignore the conductor’; he is trying for a raucous, un-‘classical’ sound. But the work itself is austere and solemn in intent ... The music spins away into a kind of gritty ecstasy ... a cool balance between ancient and modern modes, between the life of the mind and the noise of the street.”

RAYON RICHARDS

The ability to work within strict formal constraints and mesh with other artists (Sirota calls him “a virtuosic collaborator”) has opened many paths for Muhly. He has scored movies — among them The Reader, Joshua and Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret — and plays, including Broadway revivals of The Glass Menagerie and The Cherry Orchard. He has joined with choreographer Benjamin Millepied on works for major ballet companies in New York and Paris. The perpetually in-motion composer has also worked with singer-songwriters Björk, Sufjan Stevens and Rufus Wainwright, Brooklyn rock band Grizzly Bear and chamber cabaret group Antony and the Johnsons. A YouTube search turns up hundreds of Muhly items. (For a quick sample of his gestalt, check out “Nico Muhly and Ira Glass/Live from the NYPL.”)

Muhly’s idiosyncratic website highlights three dozen CDs, including his latest, 2016’s Confessions. The album is a collaboration with Teitur, a singer-songwriter and producer from the Faroe Islands, the isolated North Atlantic archipelago whose 50,000 inhabitants speak a language closely related to Old Norse. (“I’m obsessed with it,” Muhly says.) One track on the album, “Drones in Large Cycles,” is studded with little pops and skips that bring to mind an old, damaged vinyl LP, or the tiny bubbles that diffuse randomly in hand-blown glass.

These imperfections are not trivial, Muhly says.

“Teitur is so good at taking what is an incredibly clean audio landscape and letting it fuzz at the edges, so there’s a real sense of grit on the sound,” he says. “If you’re working with electronic sounds, it’s important to me that they have some sort of actual acoustic property, in the same way that the early Disney cartoons or Disney movies are sort of these beautiful watercolors. You can see the hand of the artist even in an electronically reproduced medium.”

Muhly’s compositional hand is “strange, unsettling and often golden,” in the words of critic James Jorden. Met general manager Peter Gelb observes, “He’s what we’re always looking for today in new composers of classical music — compositional voices who are original, but are also accessible.”

“Nico’s music is a bit like him as a person,” says English mezzo-soprano Alice Coote, who played a leading role in Two Boys. “He can produce the most incredibly moving, lyrical writing that can be otherworldly, or can be just a scream for humanity. And he can also create the most amazing textures in the chorus. It can be like an Elgar oratorio, huge choruses where they join together, or other ones where they’re all practically singing their own lines, working against each other where they actually created the sound of a computer, the sound of the Internet, where he’s using voices in that way. He’s like a painter — he has layers of paint that he can apply, or he can strip away. He uses the voice incredibly well that way.”

Layering, repetition, obsession, anxiety, subtle textures and juxtapositions all loom large in Muhly’s compositional vocabulary. “Quiet Music,” a solo for piano played by Muhly on Speaks Volumes, his 2006 debut CD, has “the haunting, fragmentary quality of an anthem heard from stone church steps through heavy ecclesiastical doors,” Rebecca Mead wrote in a 2008 New Yorker profile. “The Only Tune,” a song on his widely admired 2008 album, Mothertongue, deconstructs a macabre 17th-century English folk song, employing a sonic palette that includes, it is said, Icelandic wind samples and raw whale meat sloshing in a bowl. (Asked to confirm that instrumentation, Muhly emailed: “‘Only Tune’ is like, meat, hair, bones, oil, slippers ... ” .)

“I’ve never met someone with such an energy. It reminds me a bit of what I imagine Mozart would have been like.”

In conversation, Muhly can unspool a thread of associations that are at once freely conceived and disciplined, like a great jazz improvisation that takes you far from its point of departure, yet maintains a sense of unity. Describing the experience of hearing his own works performed, he says: “I’m always nervous, or I’m off to the side or I’m backstage. And that’s so much more interesting to me, to be in a weird environment and to have the sound come as if from a distance, or from over here, or some weird memory of it. Watching an opera from backstage is amazing. I would pay great money just to listen to the stage management call of a Mozart opera. It’s so fascinating, because it has its own rhythm that is completely in counterpoint to the rhythm of the music. But when you have to call things to make the lights go, and to make the scrim go down, it’s this whole other text, as it were, that the score produces.”

Friends, colleagues and patrons speak of Muhly with a blend of awe and affection.

“He’s such a prodigious talent that music seems to flow out of him,” says Gelb, recently back from London, where he took part in workshops for Marnie, Muhly’s second Met commission (a co-production with the English National Opera). The libretto is adapted from Winston Graham’s 1961 novel, which was also the basis for the Alfred Hitchcock film of the same name; it will open at the Met during the 2019–20 season. “I’ve known many composers in my life,” Gelb says. “Usually they’re very slow in getting music to people who commission them. Nico is kind of the opposite. He’s really racing ahead with enthusiasm as he composes.”

“You can’t pin Nico down, as an intellect or a person,” says Coote. “His brain is going 15 times faster than anyone else’s. I’ve never met someone with such an energy. It reminds me a bit of what I imagine Mozart would have been like. And I’m not being ridiculous. This man’s brain is like an amazing computer. He’s like a bag of nervous and emotional and receptive energy.”

In late January, Coote premiered Strange Productions, a song cycle Muhly wrote for her, at London’s Wigmore Hall. The text is based on the poetry of John Clare and a 19th-century asylum doctor’s observations of a mental patient. “Nico just seems to express life, just living each day,” Coote says. “He’s a strange, phenomenal mixture of levity — an amazing sense of humor and sense of the absurd — and at the other end, he also has the most profoundly considered, darkest view it is possible to experience in life. He’s just the most extraordinary person.”

Elena Park, executive producer of the Met broadcasts and a well-known New York arts consultant, has known Muhly since his student days. “There’s something incredibly endearing and refreshing about Nico,” she says. “Being around him is really a total joy, although a little daunting in terms of the breadth of his knowledge, dizzying speed and near-perfect recall of the most minute details. He has this genuine open-heartedness and curiosity about the world, combined with a singular way of looking at things that comes through in his music. He’ll add an original keyboard touch to Adele’s latest pop album, then turn around and write an esoteric choral piece that harkens back to 16th-century sacred music by Thomas Tallis.”

“Essentially the thing I was the most interested in, and still am, is language, just as a concept.”

Muhly is clearly a kind of polymath, a voracious consumer of culture and experience who boomerangs it all back at the world with his own spin. One of his favorite authors is Salman Rushdie, whose densely lyrical Midnight’s Children Muhly reads at least once a year. “I’m sort of addicted to his sentence structure,” he says. “You just feel like you’re in this kind of virtuosic language space, in a way that pleases me viscerally much more than [James] Joyce, where I feel like I’m always unpacking these tiny little boxes. But with Rushdie, it’s like, pow! It feels joyful and ecstatic.” Rushdie has high praise, in turn, for Muhly, with whom he has socialized. “I find talent striking,” the author says via email, “and in Nico’s case the talent declares itself so strongly and at once that one would have to be deaf not to hear it.”

That talent blossomed early. The only child of Bunny Harvey, a well-known painter and longtime Wellesley faculty member, and Frank Muhly, a documentary filmmaker, Nico was born in Randolph, Vt., and raised in Providence, R.I. His cultural and linguistic horizons were much enlarged, he says, by extensive travel as a child, including long stays in Rome and Cairo. He plunged into music when he was about 10, taking up the piano and joining the boys’ choir at an Anglican church in downtown Providence, an experience that left a deep imprint.

“They had a really divine choirmaster who was really steeped in the English tradition,” he says on Sirota’s podcast, “and [he] figured out how to have a choir of men and boys do two services a week. It was a really spectacular thing.”

A turning point, he says, was performing the Stravinsky Mass for the first time — “a wild thing to have happen to you when you’re 12.” At that age, just hearing the first four notes was, he says in the podcast, “like a really erotic experience.”

Muhly developed quickly enough that when he came to New York as a student, his fellow conservatory students and teachers — among them Pulitzer Prize winners Christopher Rouse and John Corigliano ’59 — stood up and took note.

“By the time I met Nico at Juilliard,” Sirota says, “he was already kind of a mythical figure, a Columbia-Juilliard double degree student studying English and composition and Arabic, who worked for Philip Glass afternoons and weekends, wore a colorful assortment of gardening clogs and had an affinity for dim sum.”

Corigliano recognized Muhly’s exceptional qualities early on. “Nico knew what he wanted to do, and he did it,” he says. “He would write tons of music in a week. We’d go through 30 or 40 pages and cut half of them out, or change them, and he would be happy to do it. He was a very easy student, and very likable.”

Like Muhly, many of Corigliano’s students have opted for the demanding five-year Columbia-Juilliard program. “Columbia gives them something that Juilliard can’t give them,” Corigliano says, “and if they’re able to handle the added load — and Nico certainly was — they love the challenges of learning in a way that’s quite different from a conservatory.”

Initially, Muhly had considered applying only to Juilliard. “I was so used to keeping a kind of academic rigor as the fundamental muscle of my thought, and the music was the thing that resulted from that, not a thing that itself was being studied,” he says. “The primary thing for me was thinking about words. Essentially the thing I was the most interested in, and still am, is language, just as a concept.”

Muhly has lived in an apartment in Chinatown for many years, but says he is exceptionally grateful for his time on and around the Morningside campus, first in Wallach Hall, then 47 Claremont Ave., then boarding in a faculty apartment on Riverside Drive.

“The fact that I had this whole other school to deal with downtown was a little bit complicated, but for me it was so important to live at Columbia and to feel connected to that,” he says. “My classmates at Juilliard I’m very close with, but my classmates at Columbia feel like family.”

He lauds the Core Curriculum. “I feel like there’s a limited time in one’s life when one is forced to do things outside of what one thinks one wants to do,” Muhly says. “And I think when you’re 18, the last thing you need to do is be self-directed. So, I approached the Core in a kind of bring-it-to-me way, which helped, because I would never be disappointed or underwhelmed.”

Muhly had the good fortune of landing in a Lit Hum section taught by former dean of the College (and Amherst College president emeritus) Peter R. Pouncey GSAS’69, “an unbelievable person,” Muhly says. An English and comp lit major, Muhly also has high praise for professors Julie Crawford, an expert in 16th- and 17th-century English literature and culture; Jenny Davidson, with whom he did an independent study on Dickens; and the late Edward Said, whose understanding of musical counterpoint made a deep impression.

The thirst for knowledge, critical rigor and human values that Columbia nourished continue to animate Muhly, whether he’s thinking about Glass’ Einstein on the Beach or, for that matter, Britney Spears’ “Oops! ... I Did It Again.”

Muhly recently jetted off to Las Vegas with Sirota and a friend to catch Spears’ live show, partly out of nostalgia for pop songs they enjoyed in college, partly for the same sort of reasons that drew him to Fisher as a contemporary train wreck worth thinking about.

“There’s an element of camp to Britney, obviously, but actually kind of not,” Muhly says. “I think she’s an interesting character because we’re invited to share in her struggle — although it’s unclear what exactly her struggle was, which I think is really interesting. She’s a young woman from the rural South who was put through this kind of Disney wringer, and then suddenly we are all looking at a photograph of her actual vagina as she’s getting out of a car. That level of tabloid violence against her body is extraordinary.”

Muhly gets revved up talking about Spears, who is his age. What he doesn’t do is dismiss her or make light of her travails. Where others make cruel sport, Muhly finds the humanity. “Seeing her perform was quite beautiful and strange and tragic and fascinating in a way,” he says.

Muhly has a way of winning people over. In the Mozart in the Jungle episode, after some more backing and filling, La Fiamma closes her eyes and finally delivers her verdict on the Fisher aria. “J’adore,” she says.

Former CCT Editor Jamie Katz ’72, BUS’80 has held senior editorial positions at People and Vibe and contributes to Smithsonian Magazine and other publications. His most recent CCT piece was a profile of architect Robert A.M. Stern ’60.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu