Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Reflections Upon a 50th Reunion

My first impression on arriving at Columbia was that the campus was magnificent.

Butler Library and Low Library gave it an aura of historical elegance. Fourteen massive columns rose to the Butler facade where eight names were chiseled in stone: “Homer. Herodotus. Sophocles. Plato. Aristotle. Demosthenes. Cicero. Virgil.” Low was just as inspiring with a facade that told of Columbia’s founding as King’s College in 1754.

Freshman Orientation began in Wollman Auditorium and lasted for 11 days. The orientation booklet advised, “Freshmen are reminded that coat and tie is required dress for every event listed in this program except athletic field day.”

John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, two months after the Class of 1967 arrived on campus. The first bulletin of shots being fired in Dallas came while I was listening to the radio in my dorm room. I went to the TV room in the basement of what was later named Carman Hall and watched until Walter Cronkite told us that the President had died.

Two and a half months later, the Beatles invaded America and the TV room was jammed with students seeing John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr for the first time on The Ed Sullivan Show. Sixteen days after that, Cassius Clay upset Sonny Liston to claim the heavyweight championship of the world.

Regardless of what the calendar says, those three months were when “The Sixties” began.

Some of what I was taught in Columbia classrooms seemed useless to me then, and remains useless to this day. But Contemporary Civilization and Humanities started me on a journey of analytical thinking that has served me well through the years.

I fell in love for the first time when I was in college, in keeping with the third of Shakespeare’s seven ages of man: “And then the lover, sighing like furnace with a woeful ballad made to his mistress’s eyebrow.” (As You Like It, Act II, Scene 7)

Given the existence of the Vietnam War, I hoped to avoid Shakespeare’s fourth age: “A soldier, full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard.”

I did some things that I’m proud of during my college years and others that I wish I hadn’t done because I can see now that they were foolish and hurtful.

The Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and Lyndon Johnson’s effort to build a “Great Society” were hallmarks of our college years. It would have been considered ludicrous then to suggest that, 50 years later, we’d be enmeshed in a national debate over whether children should be taught evolution or creationism in school. But it was equally improbable that the United States would elect a black President or that gay marriage would become law.

One day before we graduated, the Six-Day War broke out in the Middle East. None of us could have known then the extent to which religious hatred would endanger the world in our lifetime.

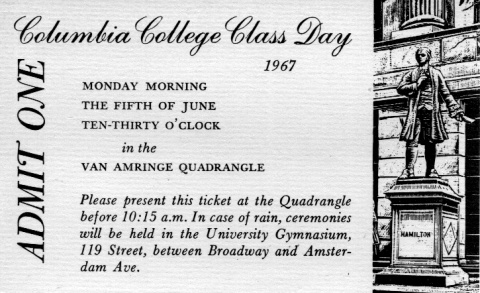

A ticket to Class Day 1967

Courtesy Thomas Hauser ’67

And we’re uncomfortably near the seventh age: “Last scene of all that ends this strange eventful history is second childishness and mere oblivion, sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

Those of us who made our way to Morningside Heights in June for our 50th reunion stepped into a world where memory and reality intermingle.

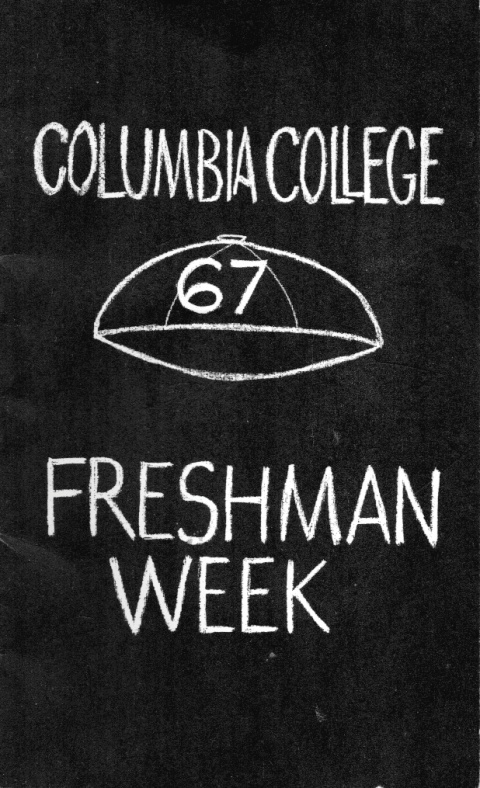

The cover of the Class of 1967 Freshman Week booklet.

Courtesy Thomas Hauser ’67

Butler and Low have retained their exterior grandeur. Butler’s polished floors, interior artwork and first-floor library are remarkably similar to the way they were 50 years ago.

Ferris Booth Hall was torn down at the close of the last millennium and replaced by Alfred Lerner Hall. Wollman Auditorium is no more. There’s a carpeted lounge in the basement of Carman where the TV room used to be, but no television. The communications revolution has rendered that need obsolete.

The students look very young. They’re the same age that we were a half-century ago. In their eyes, we’re old.

Some campus landmarks look as they did decades ago. One can stand at the bottom of the steps in front of Hamilton Hall, gaze upward at the statue of Alexander Hamilton (Class of 1778) and see what we saw during our college years. Hamilton was a son of Columbia centuries before Lin-Manuel Miranda discovered him.

Low Plaza also looks the same. I remember throwing a Frisbee there with an agile, very pretty, young woman. She died from ALS 10 years ago. When the disease was in its final stages, I sent her a card quoting Shakespeare’s 104th sonnet:

“To me, fair friend, you never can be old,

For as you were, when first your eye I ey’d,

Such seems your beauty still.”

As Columbia alumni, we moved on with our lives long ago. But as classmates, we’re held together by a common bond: We shared the same world when we were young.

Thomas Hauser ’67 can be reached at thauser@rcn.com.

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu