|

|

|

|

|

COLUMBIA FORUMDoormenSociology professor Peter Bearman’s book examines the complex dynamics between New York City doormen and tenantsFor the most part, doormen are a phenomenon unique to New York City. Though many cities have buildings with concierges or hosts, the friendly yet mysterious figure who accepts packages, announces guests and maintains order at upscale apartment buildings throughout the five boroughs is quintessentially New York. Most New Yorkers know little about their doormen; however, doormen know much about their tenants. Columbia sociology professor Peter Bearman illuminates the doormen culture in his book, Doormen. Director of the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy, Bearman developed an interest in the New York-ness of doormen when he moved from North Carolina to become a Columbia professor in 1998. Over the course of several years, Bearman worked with College students to develop an in-depth study of doormen, allowing sociology students to gain hands-on research experience while conducting hundreds of interviews with doormen and tenants around Manhattan. Bearman weaves together these interviews, observations and survey results to examine the complex dynamics between doormen and tenants, ranging from social interaction to lobby management to anxiety over holiday bonuses. In this excerpt, Bearman discusses lobby queue discipline, the effects of social talk between doormen and tenants, the little things that impact what doormen do, the ways tenants think about the doormen’s jobs, and the complex world of the residential building. QUEUE DISCIPLINE IN THE LOBBY Doormen are stuck in the middle, somewhere between clerks in high-status retail shops and dentists. For doormen, one line of argument insists that all clients are equal, or at least that all tenants are equal. This is the dental model, net of emergencies. Another line of argument insists that delivery people, who have schedules to keep, FedEx carriers who need a signature, and Chinese food deliverers with food quickly getting cold deserve quick attention. This is the high-end clerk model — some clients have queue priority. Certainly, delivery people are not happy about waiting for service, and they have the capacity to exert some structural power over residents and doormen. Serving delivery people first carries some risk since waiting for service is not a skill that the people for whom the doorman works — the building tenants — have either. Typically, they are people who in other walks of life make others wait for service. So a final line of argument is that not all tenants are equal. And the reality is that some tenants appear to the doormen to be either more demanding or more important than other tenants. This is in fact the case. But it is not advertised. Against this confusing background, if everyone arrives at the same time, the doorman has to respond in crisis mode. Decisions have to be made about priority. Some clients cannot be immediately served. If four events arrive at the same time, three have to wait. It is a simple reality. And throughout, congestion is likely to become worse. This is because arrivals arrive without respect to queues. So they are as likely to arrive when the doorman is busy as when he is free. This experience of managing the competing demands of clients induces stress. The experience of stress is heightened because unlike our relationship with cashiers at stores or even our dentist, tenants and doormen are stuck together in long iterative sequences of service, often stretching out for years. The repetition of small tasks for tenants, who are both socially distant and close at the same time, creates additional problems for doormen. They cannot prioritize their tenants’ demands by ignoring a food or dry-cleaning delivery, since the materials brought to the building are going to another tenant. Consequently, while they have to enforce queue discipline, they cannot easily commit to the specific priority scheme they adopt. The schemes are constantly changing in relation to the specific tenants who need service. Doormen face problems of enforcing queue discipline since clients with different priority are likely to arrive at the same time. While Peter was being interviewed, for example, a Chinese food delivery arrived at the door. Many doormen allocate food deliveries high priority in the queue, since delays result in cold food and unhappy tenants. Delays also keep outsiders in the lobby, and this is something doormen do not want, since they have to attend to the outsider during his or her sojourn. In this case, though, the food was brought to the wrong address. After the mistake was taken care of, Peter said:

Continuing, he describes how he enforces queue discipline when clients pile up on one another at the same time. First come, first served rules are quickly violated; the inside of the building is managed first, then the outside, unless … the client is an old lady!

Eamon describes his attempts at enforcing queue discipline with clients who are often difficult to control. Here the situation is radically different from airplanes queuing on runways or patients in a dental clinic. Instead of passive clients waiting to be served, doormen often contend with active clients content to serve themselves, if they think it is needed.

It is not always possible to line things up neatly and keep them ordered, especially when the things lined up are people with their own programs and expectations. In all of these cases, doormen try to solve problems posed by congestion that are exacerbated by simultaneous arrivals of clients, who from competing first principles demand to be served first. In some cases, the demands are illegitimate. In others, the problem of competing legitimate demands is quite common. Whether they are illegitimate or legitimate does not really change the experience for the doormen, since they still have to manage the stress of trying to accomplish too many things at once. Nor does their self-understanding of the job always provide great assistance in making decisions about how to proceed, although it helps eliminate one class of events as competing for priority — visitors and guests.

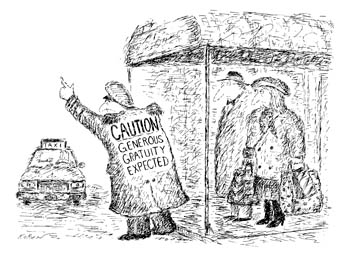

© The New Yorker Collection 1991 Edward Koren [’57] from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

TOO MUCH TALK The problem with appearing ready to serve as a strategic deployment against the perception of idleness is that at times the conversation that ensues is onerous and a distraction from other aspects of the job. As Hans says about overly voluble tenants, “Outside [i.e., as a projection, not outside the building] we can be friendly and talk, but we have to do our job first.” Likewise, Felix describes unwanted contact with his tenants as “intense at times. People do get on my nerves. The hardest thing is trying not to show them that you are getting bothered.” In some instances, tenants spend long periods talking to doormen. More typical on the swing or night shift than the day shift, doormen recognize that they are not really being asked to “talk, but to just listen.” They often see themselves as unpaid psychotherapists. Elbert describes one situation, of many:

About one old man who has no friends in the building, Billy says:

In some cases, routine small talk creates priority problems when events that need attention do arise. Tenants arriving with groceries may find their doorman engaged in conversation and consequently unable to get to the door, and doormen who use conversation to signal availability often feel unable to extricate themselves just when they want to. As Radzac says:

These winks can become encoded into specific relationships that tenants have with doormen. One tenant describes how, because he speaks Spanish with one of his doormen, they have developed a code largely inaccessible to other tenants. Using a reference to the TV show Naked City, which ends, “There are eight million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them,” his doorman says, “Another story [in Spanish],” when Richard sees him trapped in one of many long conversations. Such “special relationships” that doormen have with their tenants are not unique, although they are experienced as unique by the tenants, who tend to believe that their doormen are especially close to them, not thinking necessarily that they must be close to others as well. The successful doorman develops such special relationships with most of his tenants. The perception that doormen have special relationships extends beyond the relationship. Tenants in buildings where their doormen have worked for many years almost invariably feel that their building is unique. They are thus surprised to find that this is the case in most buildings. That tenants who talk with doormen feel that their relationship is special says something about the capacity of doormen to project closeness, despite the status differences that are always present. This projection is considered in more detail subsequently.

“Feed the plants, feed the cats, walk the dogs, wash windows. You’d be surprised what some of these doormen do just to make that extra dollar.”

MORE MOVEMENT AND LESS TALK The problem is that talk is cheap, as the saying goes. On average, though, neither small talk nor in-depth conversation with a few needy tenants is sufficient to counter by itself tenant perceptions that their doormen have too little do to or that they ignore them when tenants need them. To shift these perceptions, doormen generate services that they can do for tenants in their free time. They may appear to jump up to hand them their laundry, take an extra trip up the elevator to personally deliver a package, or rush outside to watch their tenants’ car to make sure that when parked in front of the building, it will not receive a ticket. These small services are a constant feature of the workday for most doormen. Doormen do not articulate that they engage in these services to change tenant perceptions. Rather, they talk in terms of providing professional service. However articulated, these services often tend to go unnoticed by tenants, who perceive them as either building policy or simply the way that their doorman is (except around Christmas, when the prevailing rhetoric shifts to allow tenants to interpret small services as non-normative and motivated by the upcoming bonus). Even outside the Christmas season, the provision of small extra service is not always successful. Overtly obsequious service may backfire in some cases. Donald, for example, reports how in one case he “heard one of the tenants speak to another tenant, and I guess maybe I was too polite or something; she said, ‘It’s like having an English butler working here.’ ” In describing what other doormen do, some doormen adopt a cynical attitude. Atzan describes coworkers in his building in relatively uncharitable terms:

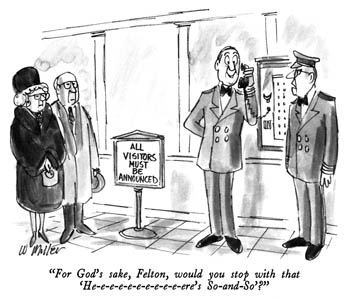

© The New Yorker Collection 1987 Warren Miller from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

As noted above, this is a view that most tenants share on the approach of the Christmas season, when tenants read doorman behavior as bonus seeking. Doormen, on the other hand, report little seasonal change in their behavior. They are wrong; their behavior does change. But tenants are also wrong. Doorman behavior (increased attentiveness) changes not as an explicit attempt to bolster the bonus but because of very subtle structural changes in the temporality of work. As the holiday season nears, the pace and intensity of work increases. In the weeks before Christmas, the volume of packages increases, and even a slight change in the number of packages received for any given day creates new queuing problems for doormen. And longer queues make it more likely that they will be busy when tenants need something. Therefore, doormen are likely to compensate as best they can when they are free, so they take the time to deliver the packages, greet tenants when they enter the lobby, and initiate conversation. Many tenants perceive this as a rather obvious attempt to bolster their bonus. In contrast, the doormen see this additional service as necessary to compensate for the busy times of the day. ...

"It can get so hectic, believe me,

Service and talk are the simplest strategies that doormen employ to shift tenant perceptions that they both do nothing and are unhelpful when needed. In reality, doormen cannot control the flow of events that enter the lobby, and so they are bound, like any server system, to be unable to serve everyone at the same time. This fact creates stress, since they have to make quick decisions about who to serve — and the priority schemes that they utilize will make some tenants unhappy. If they were always busy, tenants could become disciplined into adjusting to a first come, first served model, assuming that the door — like the pizza parlor, the grocery store, and the dentist’s office — will get to clients when it is their turn. But because doormen are often seen without anything to do, tenants become frustrated that they are not available when they need them. The main “weapon” that doormen have to counter negative perceptions that arise from a misreading of the nature of the server system they are embedded in is to shape client preferences. Grocery stores, dentists, airports, and other server systems also experiment with shaping preferences. For example, airlines develop systems for rewarding frequent fliers with shorter queues, and grocery stores induce different shopping patterns by linking specific servers to the number of items purchased. Consumers of these services make choices about their own behaviors based on the incentive structures provided by the server systems. In the absence of express lanes, people are less likely to purchase just one or two items in the grocery store. Since the average cost of each item in a small (less than ten-item) cart is higher than in a large cart, stores create incentives to attract small cart shoppers. These incentives, over time, shift purchasing behaviors. In the same way, doormen try to develop over time their tenants’ specific preferences for services. If they are successful, they gain some control over the temporality of their day; while they do not necessarily reduce stress, they do lay the groundwork for a claim of professional status. And this proves exceptionally important in the management of the lobby. Not all doormen are successful and some strategies fail. Shaping tenant preferences requires that doormen distinguish tenants on multiple dimensions. If doormen fail to distinguish tenants — that is, induce distinction — they can only treat them as equivalents, who are therefore subject to the presence (or absence) of the same formal rules. Thus, failure is first and foremost associated with a commitment to universalism and unwillingness to be particularistic with respect to conversation, service, greetings, and attention. In this sense, doormen who work to rule will fail. Another way to say this is that doormen must in relation to tenants renounce being an employee and claim professional status. The obvious tension is that, rhetorically, one aspect of professionalism entails a commitment to universalism. For example, doctors should treat all persons, whatever their capacity to pay for services. Likewise, one would consider lawyers who do a bad job for some kinds of people (those who cannot pay, those whom they do not like, etc.) unprofessional. But this is simply a rhetorical structure, for the salient indicator of professionalism is the capacity to act substantively against the demands of blind formal application of rules. Doormen commit to the professional norm to serve, but this commitment entails inducing differences among tenants so as to serve them better. When doormen fail to differentiate across tenants, they are likely to develop negative attitudes toward them. This is often followed by exit, for doormen who seek protection from discretion must work to rule, an experience deeply frustrating for both tenants and doormen.

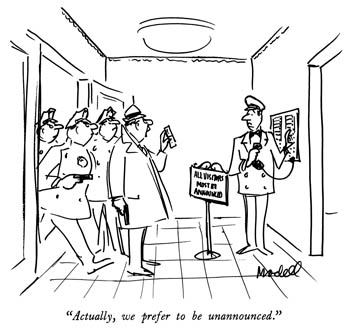

© The New Yorker Collection 1989 Frank Modell from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

INDUCTION OF DISTINCTION FROM THE LITTLE THINGS W hen guests arrive, doormen can hold them in the lobby and phone up to the apartment for confirmation that the guests are invited. Alternatively, doormen can send the guests on their way, phoning as soon as they step into the elevator. Or they can just send them up unannounced. When packages arrive, doormen can hold them in the back, bring them up, phone ahead, or keep them at the front desk. Videos can travel upstairs with or without warning or be held at the front desk. If cars come early to pick tenants up, doormen can call up to tell the tenant that their car has arrived or wait until the scheduled time for departure before calling. Dry cleaning can be laid out in public or stored in the back. When children come down to play, doormen can watch them or let them be. If while the parents are gone their teenagers had a party, the doormen can tell the parents or not. These small things and hundreds of others should seemingly be inconsequential. And in most instances they are. But they need not be. If unexpected guests are announced over the phone while they are downstairs, tenants who don’t feel like socializing with them are caught at home and could feel trapped by the unexpected visit. Better for some would be prior warning that Mr. X and Ms. Y were on their way up. Tenants may want to avoid tipping their delivery person; if so, doormen might hold food and videos until after the delivery. Some parents may want the doormen to watch their children when they are playing out front; others may find that intrusive. The doormen do not care which preferences their tenants have, only that they have preferences and they know what they are. If tenants do not have preferences, doormen help them acquire them. As Tito, who works on the swing shift in a small building on the Upper East Side, says:

Training tenants to have preferences is interactive. Doormen may bring packages up to tenants and ask, “Would you rather I just held it for you downstairs”? Likewise, if kids come down to play, the doormen may call up to the apartment and say, “Hi, Mrs. X, this is the front desk. It’s no problem for me to keep an eye on the kids. You want me to make sure they don’t get off the sidewalk?” Repeatedly, doormen will work to find just that mix of services that tenants want. When they find it, they stick to it, often reminding the tenants that this is in fact what they want. As Bob says:

These little tricks of the trade provide the framework for inducing tenants to have and communicate preferences. The induction of distinction across tenants is important not because it provides better service — most of the distinctions are trivial enough to be within tenants’ zone of indifference — but because it provides a solution to the management of time in the lobby. Or more precisely, because it begins to solve some of the problems associated with the experience of time — of too much and too little to do, and tenant perceptions thereof. Excerpted from Doormen by Peter Bearman, reprinted by permission of the publisher. © 2005 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved ($25).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||