|

|

|

|

|

|

|

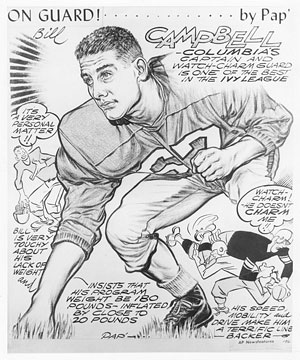

COVER STORYThe Coach of Silicon ValleyBill Campbell '62 captained Columbia's Ivy League football champions

and coached the Lions for six seasons before beginning a successful

career in high-tech industry.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

PHOTO: MILES KEEP |

Let’s start this story at a bar. Not such a bad place to get going, right?

But you’d think because the story is about a pretty prominent

fellow — who's been CEO of three high-tech companies, hangs

around with the likes of Steve Jobs and other Silicon Valley legends

and is a Columbia trustee — you'd figure the bar would be

some place like the Oak Room at the Plaza or the Top of the Mark

in San Francisco. Some place with power-

broker panache.

Not for this guy. Chiodo’s Tavern is in gritty Homestead, Pa., a nine-mile drive from downtown Pittsburgh and a zillion miles from snooty. It’s on West 8th Street, not far from where U.S. Steel used to employ a lot of folks when the town had 20,000 or so people. After work, guys from the mill would come to Chiodo’s for a beer and rage on about the Steelers or the Pirates or their crummy bosses at the mill — and laugh a lot. Even after U.S. Steel shut down in 1987, accelerating an exodus that now leaves the town with about 4,000 residents, the regulars still come into Chiodo’s.

“It's a working man’s bar,” says owner Joe Chiodo. "I have a lot of things hanging from the walls. Footballs, baseballs, trophies and apparel that young ladies wear." Chiodo has been collecting this stuff since he opened the place in 1947. He tells a visitor about a picture on a wall, a picture of the guy this story is about. The guy grew up in Homestead, son of a mill worker, watched the Homestead Grays go up against other Negro League teams with his dad, played guard and linebacker at Homestead High, then went off to college in New York City. He played football there with some success and coached football there with less success, then scrapped the coaching and went into business — and made a big deal of himself.

But even though he never moved back to Homestead, the guy in the photo didn't forget Homestead, either. “My place has been here 58 years, and I'm always proud to say, ‘This is Billy Campbell,’” Chiodo says as a way of introducing the photo and the guy in it, “the young man from our hometown who gave so much to our hometown.”

|

Campbell with Intuit

founder Bill Cook (left) and Campbell's successor as CEO,

Steve Bennett. |

Chiodo calls him Billy. People in Silicon Valley, where he consults for such companies as Google and drugstore.com and Tellme, call him The Coach. Shareholders of Intuit, maker of the popular personal finance software TurboTax and Quicken, call him Chairman of the Board. But maybe the nickname that really gives you a good idea of William V. Campbell ’62 is Ballsy, which is not exactly the kind of name you’d expect for a guy who has been compared to such luminary businessmen as Jack Welch and Bill Gates.

That’s why the story of Bill Campbell is so unusual. In one way, he has more layers than a wedding cake, and in others ways, he’s as simple as a bottle of Bud Light. There’s a lot about Campbell that makes you scratch your head. Like this: By 1979, at 39, he had never worked a real office job; he’d been a football coach since graduating from Columbia, including six losing years in the mid-1970s as the school’s head coach. But during the next 15 years, he became CEO of three Silicon Valley technology companies, including Intuit, where revenues have risen from $200 million to $2 billion since he arrived in 1994. Or, that while he weighed only 170 pounds when he played guard and linebacker for Columbia from 1958–61 and regularly faced linemen 20, 30 and 40 pounds heavier than him, he was still good enough to be named captain in 1961, the only year Columbia won an Ivy League title.

Or, that while he holds seats on three corporate boards and was named a Columbia trustee in 2004, his favorite seat may be at a table in a Palo Alto, Calif., pub called the Old Pro that’s inscribed “Coach’s Corner” in his honor. Or, that while he’s known to hang out at the Old Pro well into the night, by 5 the next morning, he’s up to work out and then on his way to make the rounds of the companies for which he consults, do Intuit work, coach an eighth-grade flag-football team and still be home in time to help his daughter, Maggie, with her homework. “He has been given the gift of energy. It is so rare,” says Roberta Campbell, who met her husband when she was Columbia’s dean of residence halls in the 1970s.

Or, finally, that while he may only stand 5-foot-11, his reach is enormous. There are the 30-plus CEOs, including those at VeriSign, Good and Adobe, who at one time worked for and were mentored by Campbell. Bruce Chizen is one. In the late 1980s, Chizen was a sales rep pushing Apple products in New York City. One day Campbell, then Apple’s v.p. of sales and marketing, suggested to Chizen that his career would accelerate a lot faster if he moved out west. Chizen took the nudge. “When Bill suggests,” Chizen says, “you know you have to listen.” Once in California, Chizen got a free B-School education from Campbell with regular lessons in engineering, budgeting and procurement — stuff most sales guys wave at. “There was a lot about business I didn’t know, and there was a lot about business I didn’t care to know. Bill forced me to care,” says Chizen. “He had this great confidence in me, more than I had in myself.” Chizen now is CEO of Adobe. “If it weren’t for Bill Campbell,” he says, “I wouldn’t be in this position.”

|

Campbell (No. 67)

leads a sweep around right end for the Lions. PHOTO: COLUMBIA ATHLETICS |

Marty Cicco ’78 says much the same thing. Thirty-one years ago, Cicco was a highly recruited high school football player in Pittsburgh. He picked Columbia, a school whose football team had just one winning record over the previous decade. The reason? “I came to Columbia solely to play for Billy Campbell,” says Cicco, one of Campbell’s first recruits when he took over the program in 1978. Injuries cut short Cicco’s Columbia career, and during his four years on campus, the team went 8–28. Still, Cicco does not regret his decision. “I have had a reasonably successful career,” he says, downplaying his job as head of Merrill Lynch’s Global Real Estate Investment Banking division, “and I owe the job solely to Billy.” Through Campbell’s connections, Cicco got a summer job at Merrill after his junior year that led to a full-time job. He’s one of several Columbia alumni with a similar story. “Billy felt he had an obligation to every kid he recruited to be there in all aspects of a player’s life, not just on the football field.”

One season, when Campbell was coaching, he was driving on worn-down tires. “He was making $35,000 a year,” remembers John Cirigliano ’64, godfather to Maggie and a corporate investment adviser. “I went to the athletics department and said, ‘You need to get him a set of new tires. He’s going to drive off the road.’ ” These days, Campbell’s donations to Columbia stretch into the millions and have been used for everything from current-use scholarships to refurbished athletic facilities. He also sponsors a party the night before Homecoming, a chance for old football buddies to reunite, laugh and remember. “Each year, we have a theme and honor a group of people, but in three of the last five years, we’ve honored somebody who has passed away,” says Michael Griffin, who worked in the athletics department for several years before becoming Columbia’s associate director of alumni relations last fall. “Bill was very generous about making sure the next of kin were able to be there.”

And, of course, don’t forget Homestead. Its high school has a new, million-dollar turf football field because of Campbell, and he gave another million for computers that the kids can use. Last year, he sent Homestead Mayor Betty Esper $20,000 to put computers in police cars. Esper, who goes by Bo, grew up a couple of houses down the block from the Campbells. She’s lived in Homestead all of her 71 years, and has watched as the town’s waterfront became dilapidated and U.S. Steel closed. With all that’s happened to Homestead, it’s easy for a mayor to lose hope. “Once the horse leaves the barn,” says Esper, mayor since 1990, “it’s hard to get the horse back, and that’s [the truth] for every main street in every small town.” Still, she doesn’t lose hope, thanks to Campbell.

Before he was rebuilding football stadiums and paying for computers, Campbell would drop small donations in the mail for Esper, like $1,000 so she could put on the town’s annual Christmas parade. “Billy always told me, ‘There is never a time you can’t call me,’ and this was before he got this well-known,” she says. “I remember a time when I called him and we got to talking about Homestead, and I remember at one point he got choked up — because he misses home, he’s still a hometown boy — and he said, ‘You know, Bo, one of these days, when I’m able to, I’m going to do something for my hometown.’ And he has certainly done it. He has never forgotten his roots. If everyone was Billy Campbell in these small towns and gave back, it would be a better world, for sure.”

So, Ballsy, tell us how you did it — how did you go from being a kid from Homestead, Pa., to a Silicon Valley go-to guy who’s always there for favorite causes?

“I’d rather not,” he says, “I hate these things.” “These things” being interviews about himself. Campbell has a voice so raspy you’d think his larynx had been chewed on by a Great Dane. He doesn’t sound like the sweetheart guy everyone talks about. He explains that doing interviews detracts from what he does best: building collaboration in organizations, not stars. Plus, “I don’t like to get my name in lights.”

Then, just when you think he’s about to say, “See ya,” instead you hear, “Go for it.” And then it’s hard to shut the guy up.

|

|

"Billy felt he had an obligation to

every kid he recruited |

October 7, 1961. Princeton versus Columbia. Baker Field. Temperature: North of 90 degrees.

Coming into the season, there was talk among the seniors that this team had a shot at winning an Ivy title, even though the school’s last winning season was 1953 and the team was coming off a 3–6 season. This also was still the era of guys playing offense and defense, meaning it was critical that a team have a deep bench, but the ’61 team had lost two key players before preseason camp broke.

Campbell, the team captain, a 170-pound offensive guard and linebacker, saw something different in this team. A few weeks earlier, after playing a scrimmage against Bucknell at Baker Field, the team had elected to go back to Camp Columbia, a utilitarian outpost in Connecticut where the Lions held preseason training. “That was a big deal,” Campbell says. “A different group would have said, ‘Let’s stay on campus; it’s a lot easier.’”

“You had the right mix of kids,” remembers Al Butts ’64, a sophomore on that team who went on to a successful career in hotel management. “The leaders on that team were from [small towns in] Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and upstate New York. They were about blocking and tackling, no fancy stuff.” They had fun nicknames, too. On the offensive line, besides Ballsy, there was Lee “Bugle” Black ’62 and Ed “Moonsie” Little ’62. Plus, they had the ideal coach for this mix: Aldo T. “Buff” Donelli. “Pennsylvania-tough-as-nails,” Butts says of Donelli, who had coached several years earlier at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. “Kind of from the Vince Lombardi school.”

Donelli recruited players, Campbell remembers, who would understand that “to break the [losing] mold you were going to have to allow yourself not to go over to the whiny side of making excuses of why we can’t win. He wouldn’t listen to them.”

Facing Princeton, a team Columbia hadn’t beaten in 16 years, the Lions had a chance to show just how different they were. Early on, they did just that by taking a 14–0 first-quarter lead. But as Campbell remembers, it could have been 21–0. Columbia drove inside the five-yard line, but four plays produced nothing. “We could have put it away,” says Campbell.

Still, it was 14–0, and Donelli figured it was a good time to give some of his starters a rest, considering the big lead and the heat. But with just seconds to go in the quarter, Princeton connected on a 72-yard pass play and the score became 14–7. By the half, it was 15–14 Princeton.

In the fourth quarter, Princeton led 23–20 when Columbia took over with the ball on its 43 with under 12 minutes remaining. How different was this team? During the next six minutes, Tom O’Connor ’63 and Russ Warren ’62, who would gain 123 total yards on the day, alternated taking handoffs and running up the middle through holes that Bugle, Moonsie and Ballsy created. Eventually, they reached the Princeton 13-yard line, where on fourth down and four, Donelli chose not to settle for a game-tying field goal. He wanted the lead. As the team huddled, everyone figured Warren or O’Connor would get one more crack. But at the line of scrimmage, quarterback Tom Vasell ’62 called an audible, a quick pass to the weak-side end. Vasell’s throw was just a touch behind Ron Williams ’62 and fell incomplete. Drive over. Princeton’s ball. One play later the lead became 30–20, the final score.

“I will never forget it,” Campbell says. “It was brutal.”

Another loss — and after a 14–0 lead that could have been 21–0. Why? Was it the heat? The lack of depth? The audible? Campbell says he had never been so exhausted after a game. But Donelli didn’t want excuses.

And Campbell wasn’t one to give them. In high school, he was named MVP of his football team. He also led Homestead to a state title in volleyball. “He made volleyball a contact sport,” says his brother, Jim. When the Homestead track coach found himself short of hurdlers one season, Campbell volunteered. “He couldn’t even jump,” says Jim, younger by two years. “But he ran through every hurdle and ended up qualifying for a regional championship.”

For Jim Campbell, a 6–2 All-American wide receiver on the Roger Staubach-led Navy teams of the mid-’60s, his “little” big brother was always the go-to guy. “We played on the same basketball, football and track teams. And in every case, he was the organizer, the leader, the inspiration. He made everything a passion.”

Some of that drive came from Homestead, which made people tough. “It was just a blue-collar, steel-working town,” says Jim, a manager of golf resorts in the west. “If you don’t bust your ass, you don’t make it in that town.”

Plus, the Campbell boys had a pretty good idea of what hard work involved. “My dad was a tough bastard,” Bill Campbell says of his father, William Sr., a World War I veteran. “We had one car when I was a kid, and my mom used to drive us down to the mill to pick him up. He had worked the midnight-to-8 shift, and would come out in a jacket and tie, and we would drive him to school, where he would teach all day. He would go home after teaching and sleep for a few hours and then go back to the mill.” Bill Campbell Sr. kept up the double duty until he became a school superintendent and “made enough money so that was all he had to do.”

Bill Campbell Sr. also knew Donelli. When Donelli was coaching football at Duquesne, Campbell Sr. had another job, as the school’s basketball coach. So when Campbell started looking for colleges, his dad pointed him toward Columbia and Donelli.

Columbia? New York? Ivy League? Was that the right place for a kid from small-town Western Pennsylvania, from a high school where only 10 or so of the graduating seniors went on to college? In fall 1958, Campbell headed east to find out. “I remember having to write my first 500-word essay,” Campbell says of his freshman days. “I used to have to write one a week. That was the worst part of my life. I counted the words.” Then there was the assignment to find symbolism in Dante’s Inferno. “I didn’t know what symbolism meant.”

Campbell picked Columbia largely because of the chance to play football, and the transition to Ivy League play was easy. It was in the classroom where he felt the competition. “I didn’t know I was going to be up against students who went to Bronx Science and Boston Latin. You’re from this small town and you figure, ‘Boy, I have to catch up and pay attention.’ All of a sudden you find that the competition is fun — to try to understand what other people either are trying to understand or already understand. The idea is that there is a certain root in that intellectual curiosity that forces you to conclusions of understanding that help in everything you do in your life — you understand your wife, you understand your kids, you understand your co-workers. I think the Columbia education helps you do that.”

Sounds good, in hindsight. At the time, Campbell was just trying to get through calculus, chemistry and the other quantitative courses he gravitated toward. Eventually, he majored in economics, with his adviser, Professor Bob Carey, playing a big role in that decision. “He convinced me that I could do this. I would go to his office and talk about economic concepts, and he could bring those concepts into practical reality and show how they were applied.” But when it came to non-quant courses, Campbell quivered. He blamed it on an inability to conceive things. Whenever they’d see each other at basketball games, a certain professor would pester Campbell to take his 18th-century English lit course. Finally, junior year, Campbell, broke down. At the first class, “I sat there and listened to all these [students] talking who understood the reading,” Campbell recalls. “Then, all of the sudden, the professor calls on me. He wants to know what I think. I told him, he said, ‘Good point,’ and went on. And I said to myself, ‘Maybe I do belong here. Maybe I can give my view on some great work of 18th-century literature.’”

He may have hesitated in that classroom, but when it came to football, Campbell never doubted himself. He became a team leader, pushing guys to work harder in the training room, and showing them how. “He had a 17-inch neck. That wasn’t natural without steroids,” says Jim Campbell. As Butts puts it, “Basically, he was a tough kid and everyone respected him. If there was a fight, you knew he would be out in front.”

And that’s what happened after 30–20 Princeton. The ’61 team had a fight, between making excuses or not. The decision: Columbia won its five remaining Ivy games and captured its only Ivy League title, sharing it with Harvard, which Columbia had beaten on the road. “Other than getting married and having your kids, nothing could be more important than that,” Campbell says of the championship. “It was a magic season. You had guys who were in a small, tight group. But we stayed really close. We still are close today.”

"He worked harder than anybody. He was always motivating." |

If a happy ending eventually followed that Princeton loss in 1961, the same hardly could be said of another Columbia loss to a New Jersey school. Seventeen years later, on October 28, 1978, Rutgers embarrassed Columbia 69–0 at Giants Stadium in the Meadowlands. Campbell was then in his fifth season as Lions head coach, and if he needed one more reason to quit the profession, this was it.

“When you look at it from a distance,” Campbell says of his coaching stint, during which the team went 12–41–1, “I wasn’t very good.” Perhaps, but some would argue it wasn’t the coach; it was the situation, contending that the school’s support for the football program was at an all-time low in the mid-’70s. Remember, this is pre-Wien Stadium. The wooden structure at Baker Field was a crumbling eyesore, hardly a facility to draw much talent.

Campbell knew the constraints going into the job — he just expected to overcome them. To once again ignore the whiny noise and the excuses. He remembers the day he took the job, and has a picture of the press conference at his home. “I had a lot of people tell me it would be a graveyard for me,” Campbell says of his return to Morningside Heights. He had stayed on at Columbia after graduating in 1962, getting his master’s at Teachers College while serving as assistant coach under Donelli. In 1968, he moved on to Boston College, where he helped build one of the top defenses in the country. “I felt, though, that we had won when I was there and there was no reason we couldn’t win again.”

“When he came back, we were all so happy,” says Cirigliano, who had played lightweight football at Columbia. “He was going to take the program beyond where it had been.”

Campbell had two goals at the start: use his high energy and rah-rah manner to breathe some enthusiasm into the players, the student body and the alumni. “And maybe try to steal a few wins,” he says, “because we weren’t quite good enough, personnel-wise.” He started recruiting like mad, heading to the same kind of haunts Donelli once did. He preached to high school kids like Cicco that they were going to be part of a turnaround. “There was a high degree of intensity and enthusiasm and energy. He got everyone focused,” says Cicco. “He worked harder than anybody. He was always motivating.”

Campbell’s first two Columbia teams didn’t steal many wins, three in total. Perhaps his biggest win, though, came in 1976 when he married Roberta Spagnola, who at the time was Columbia’s dean of residence halls, the school’s first female dean. She, like Campbell, was from a tough neighborhood, having grown up in the shadows of Newark, N.J., but she found her way to Teachers College. They met when Campbell was at Boston College, but didn’t date seriously until he returned to Columbia. And their early romancing included some professional issues. As Campbell’s wife recalls, one day, “I had to call him to tell him we were throwing a couple of his players out of the dorms.”

By fall 1978, Campbell was starting to feel pressure, not from the school but from himself, after four seasons and just eight wins. The 1978 season offered promise, though. The team was coming off a 2–7 season, but the blowouts were fewer. The Lions surprised a lot of people by getting off to a 3–1–1 start. “I said, ‘This is the breakthrough year,’” recalls Cirigliano, who watched many of the games seated next to Roberta Campbell. “And then we played Rutgers.”

It was an ugly, chilling game, even for those not playing or coaching. Campbell’s wife could feel, and hear, her husband’s coaching career go kerplunk that day as she watched from her Giants Stadium seat. “If people didn’t know who I was, they would say some outrageous things, as fans do when coaches and players aren’t doing well,” she says of that day. “And then I had to deal with the aftermath, of how he felt about it. It was so humiliating and depressing.”

From the losses that kept piling up (the Lions lost 11 of their next 12 games through the end of the ’79 season) to the lack of administrative support to the pressures of recruiting (at one point Campbell checked into a hospital for exhaustion), the coach was reaching a crossroad. Sure, he had built a strong alumni network for his players to tap for jobs, and he kept morale on the team as high as possible. But he knew, for credibility’s sake, he needed wins. And they weren’t coming. Midway through the 1979 season, Campbell announced his resignation. The turnaround wasn’t happening. “Billy’s coaching career was marked by a great deal of enthusiasm and intensity,” says Cicco, “and because of that, he probably got to burnout stage quicker.”

Blame burnout. Blame the school and the situation. Blame New York City and what it was like in the mid-’70s. Blame what you’d like. But Campbell takes the blame and won’t make excuses. After he tells you he just wasn’t a very good coach, he pauses, looking for the right words. “There is something that I would say is called dispassionate toughness that you need [as a football coach], and I don’t think I have it,” he says. “What you need to do is not worry about feelings. You’ve got to push everybody and everything harder and be almost insensitive about feelings. You replace a kid with another kid; you take an older guy and replace him with a younger guy. That is the nature of the game. Survival of the fittest. The best players play. In my case, I worried about that. I tried to make sure the kids understood what we were doing.”

Another pause. “I just think I wasn’t hard-edged enough.”

Then how was he going to survive in the business world?

|

PHOTO: COLUMBIA

ATHLETICS |

You’re 39 years old. You have a wife and one day you’ll have two kids (Jim ’04, who played football at Columbia, and Maggie, now in eighth grade). You’re out of work, and the only thing you have on your resumé is football coach — and now, after failing at Columbia, you want out of coaching. What do you do?

Campbell called some of his Columbia football buddies, such as Butts, Cirigliano, Warren and Joe O’Donnell ’64, who was Campbell’s back-up at guard on the ’61 team. Each gave the captain contacts and friends to get in touch with. Warren knew John Sculley, then the CEO of Pepsi. Cirigliano’s Rolodex pointed him to people on Wall Street. Butts had contacts in the hospitality industry. And O’Donnell was on his way to becoming CEO of J. Walter Thompson (JWT), one of the largest advertising agencies in the country.

But what could a less-than-successful football coach offer any company or industry? O’Donnell, then living in Detroit, where he headed the Ford account for the agency, remembers flying into New York to talk with his teammate and Alpha Chi Rho fraternity brother. “He was questioning what would happen in business, would he be good at it?” O’Donnell recalled. So he reassured him: “There are a lot of parallels between coaching and business. You have to be well organized, you have to work hard, you have to be able to talk to a wide variety of constituents: In business, it’s clients and co-workers; in coaching, it’s the parents, the kids, the faculty. On the surface, it looks like two different careers. But when you look from a business perspective, you look for parallels — what skills do they posses that could be applied to another arena?”

O’Donnell arranged for Campbell to meet Don Johnson, then JWT’s CEO, which led to an offer that Campbell accepted over a job Sculley found for him at Pepsi. He moved to Chicago to work on the Kraft account. Sure, friendship played a part in getting business novice Campbell a job on a key account, but, O’Donnell says, “If he were a boob, I never would have recommended him. There was no question he would be successful.”

Campbell showed he was a quick learner, putting his background to use in analyzing his client’s business trends and market needs. Within six months, he moved back to New York to work on the Kodak account. Campbell proved to be so effective that Kodak hired him away from JWT, and in 1983 assigned him to London where he was general manager of Kodak’s consumer products in Europe.

That is, until he got a call.

“Going out to the wild, wooly west, where it was more a meritocracy, I would have a chance to move quickly.” |

Sculley, now the CEO of Apple Computers, wanted Campbell to join him in Silicon Valley, where the Macintosh computer was months away from coming to market. Campbell hesitated. To stay at Kodak meant international experience, a chance to live in London. But it also meant one day returning to Rochester, N.Y., Kodak’s headquarters, and working at a large, bureaucratic company, prospects that didn’t sit well with either Campbell or his wife. By now, he was 43 and eager to move up the corporate org-chart. After several more calls from Sculley, meetings with Apple founder Jobs and other key execs and a look at the top-secret Mac, Campbell said yes.

“The opportunity to come to Apple was huge,” Campbell says. “My career had been blunted by a lot of years as a dumb-ass football coach. I felt that because of my background, I would always be below my peer group and trying to catch up. Going out to the wild, woolly west, where it was more a meritocracy, I would have a chance to move quickly and sit on the management team.”

Within nine months of joining the company in spring 1983, Campbell was promoted to v.p. of sales and marketing. He was in charge of putting together a sales force and reaching agreements with retailers to carry the Mac. Besides earning a reputation as a fast thinker and problem solver, he also became known as a manager people wanted to work for. “He has an extraordinary ability to connect with people and make them feel good about working for him,” says Donna Dubinsky, who worked for Apple’s Australian division at the time. “You see a lot of smart executives, but rarely do you see somebody who can connect with people at all levels of the company like he can.” Campbell is known, for example, for remembering the colleges that the children of customer service reps attend and asking administrative assistants for insight into a company’s corporate culture.

But for all the excitement that came with launching the hugely successful Mac and the legions of followers he was gaining, Campbell couldn’t avoid a business world where dispassionate toughness came into play. “As time went on, I was no longer the fair-haired boy,” Campbell says. “I had been hired by Sculley as the war-time guy — handle everything that was broken and things that needed to be fixed.” When it came to peacetime, the two often would disagree on issues such as pricing and market share strategy. Looking for a new opportunity, Campbell proposed to Sculley that he lead Claris, a software division that Apple was thinking of spinning off. After several rounds of negotiations, Sculley agreed.

Once again, Campbell was in charge. The difference? This time, instead of trying to recruit talent to a small, Ivy League football program, he had the cachet of running an entrepreneurial Silicon Valley company that offered an ideal opportunity for programmers and clever marketers to try their stuff. And word was out that Campbell was a boss people wanted to be around. Dubinsky, for example, left her Australian post when Campbell asked her to join Claris. “He never told me what my salary or title would be. I just knew Bill would be fair,” says Dubinsky, who later founded Handspring, maker of a popular PDA.

Randy Komisar, then an attorney at Apple wondering about his career path, remembers that Campbell approached him in a dark boardroom one day and, in a hushed tone, told him about the Claris start-up. After just five minutes, “He looked at me across the table and said, ‘Are you in or are you out?’ He hadn’t offered me a position or salary or job title … And right there, I said yes. And it turned out to be the best thing I had done in my life.”

Under Campbell and his team, Claris quickly took off, earning more than $100 million in revenue in three years. So confident was Campbell in Claris’ prospects that he was prepping to take it public in 1990, until Apple pulled the rug out with a last-minute decision to buy it back. “We were furious,” says Campbell. “We stayed a while, and made sure the integration back into Apple was complete, and then everybody left.”

Where did they go? Many joined Campbell on his next venture, GO Corp., where he was CEO of a company in the fledgling pen-based computing world. As it turned out, GO was too fledgling, and over a three-year span burned through enough cash to make future dot-com busts look innocent. Campbell logged 18 trips to Japan in hopes of securing partners, and at one point he thought he had a deal with Compaq that would give GO a significant lift. But by 1993, GO was gone. “Oh, it was a failure,” Campbell doesn’t hesitate to say.

But GO did not break him. In fact, Campbell and his staff won accolades for keeping GO afloat for as long as they did, and in 1994, six months after GO’s demise, Campbell was recruited to be president and CEO of Intuit at a critical time for the financial software company. Scott Cook, founder and CEO, was looking for a successor just as Intuit was merging with another software firm, ChipSoft, that would nearly double the company’s revenue. Cook needed a CEO who could integrate a business strategy to propel the merged companies and also assimilate the people and cultures of the two organizations. In their book, Inside Intuit, authors Suzanne Taylor and Kathy Schroeder write, “Intuit searched for a strong leader who championed development of people. Management discipline, careful measurement of business outcomes, process improvement and operations excellence.” The job description fit Campbell, who by then, even with the demise of GO, had proven he could lead a team, set vision and inspire talent.

Since his arrival, Campbell and Intuit have gone through a series of momentous events, including an aborted merger with Microsoft, the emergence of the Internet and the need for the company to respond to this new sales channel, and cycles of strong revenue growth. Campbell turned over the CEO reins to Steve Bennett in 2000, and for all his success, says he has no interest in running another company. “Those days are over,” he says. Plus, “I’m too loyal to Intuit.”

Campbell does have time, though, to share his management practices — focused on team building and consensus gathering — with seasoned execs and new entrepreneurs. Campbell and Jobs can often be seen walking the streets of Palo Alto, talking strategies for Apple. And Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin have used Campbell as a sounding board during their company’s fast rise. Campbell declines to talk much about what advice he’s provided the Google execs, but Gordon Davidson, a prominent Silicon Valley attorney, says, “After Warren Buffet, Bill is the one Sergey and Larry look to for guidance on how to manage and motivate people.”

|

“To be honored

by your school, your friends, is just an amazing thing,”

said Campbell upon receiving the Alexander Hamilton Award

for distinguished service and accomplishment, the College’s

highest honor, in November 2000. A contingent of bagpipers

and drummers from the New York Police Department’s Emerald

Society surprised Campbell and added to the festive occasion.

PHOTO: EILEEN BARROSO |

On a wet, cold night last December, some of the biggest names in pro and college football plowed into the grand ballroom of New York’s Waldorf-Astoria for the National Football Foundation and College Football Hall of Fame annual awards dinner. Joe Paterno was there, and so was Steve Spurrier, Bobby Bowden, LaVell Edwards, Barry Alvarez, Vince Dooley and hundreds more. Ray Guy was inducted into the Hall that night, as were Joe Kapp and Jack Tatum. But the prime honoree was Campbell, who was there to receive the 2004 Gold Medal, an award given annually to “an outstanding American who has demonstrated integrity and honesty, achieved significant career success and has reflected the basic values of those who have excelled in amateur sport, particularly football.” Previous recipients include seven U.S. presidents, including John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan.

Impressive company, but before the dinner starts, Campbell is introduced to someone from his home state of Pennsylvania.

“You came all the way for this?” he asks the stranger.

“Hey, this is a big award,” the guy says.

“Shit, this is nothing,” he says, then smiles and gives the stranger a hug.

Midway through the dinner, Campbell is introduced by retired U.S. Army General Tommy Franks. “Coach Campbell, an innovator and entrepreneur, applied the lessons he learned from football to become one of our nation’s top business leaders,” says Franks. “Bill, it is my pleasure to present the Gold Medal to the man they still call Coach Campbell out in Silicon Valley. The back of the medal reads: ‘For a lifetime of leadership as coach, business visionary and humanitarian.’ ”

With that, the crowd rises. There’s Franco Harris, Archie Griffin and Archie Manning, as well as Butts, Warren and Cirigliano. Campbell receives his medal, and begins a short speech. “People have asked me in Silicon Valley, ‘Why are you in high-tech?’ I ask them, ‘Have you seen my football record?’ ” The crowd laughs. Then he says that football taught him about teamwork and supporting others. But most of all, he says, he learned that he had a responsibility to “give something back.”

On this night, Campbell is referring to Play It Smart, a program he and the National Football Foundation have developed to provide tutoring assistance for disadvantaged kids who play football. But he could be talking about giving back to all the people and places that have helped him along the way — such as the football players he recruited to Columbia, whom he still checks in with on a regular basis. Or Columbia, which has been the grateful recipient of his money and his counsel. Not only is Campbell an active trustee, but he frequently calls current football Coach Bob Shoop during the season to say, according to Shoop, “Hey, man, chin up. I’m thinking of you.”

And, of course, there’s Homestead, where his donations are always welcome, as is the man. Each summer, Campbell brings friends from Palo Alto to Homestead. They might catch a Pirates game, but they always would stop in at Chiodo’s Tavern, stay late, drink lots of beer and laugh.

This summer may be different, though. Chiodo’s is slated to close sometime this year. Walgreen’s is taking over the block where Chiodo’s has stood since 1947, and its owner, Joe Chiodo, is now 86 and ready to take it easy. Plus, maybe it will help the town, as there has been some revitalization going on in Homestead. But as much as the town may be changing, Chiodo never forgets.

“Oh, young Campbell, he was always a likeable fellow,” Chiodo says. “When he was young, he worked as a pin boy at a bowling alley for my brother and his uncle.” Chiodo pauses, then adds, “He was always a hustler.”

Charles Butler ’85, a Journalism School Knight Bagehot Fellow, is an editor for Runner’s World in Emmaus, Pa.

WHAT THEY SAY ABOUT BILL CAMPBELL“I joke around and call Bill the owner of the [Columbia football] team. He is a model for what you would hope for in loyalty to an institution. He made a true commitment to this football program when he came back as the head coach, and it was probably one of his biggest disappointments that he wasn’t able to turn it around. Had he stayed, he may have been like [former Yale coach] Carm Cozza and been here for 30 years, but that would have precluded him from becoming the [success] that he is today. In a weird way, he has probably given more back to Columbia because he was not a great football coach.” — Bob Shoop, Columbia head football coach

“When you have a chance to be around Bill and see what he was able to accomplish, not only as a football player but also as a coach and now as a chairman of a company, and [consider his] mentoring and helping other people grow their businesses — that path is one where you constantly improve other people’s lives.” — Ronnie Lott, former NFL All-Pro defensive back and managing member of the investment firm HRJ Capital, Woodside, Calif. “Bill was the football coach at Columbia when I played basketball there. I used to spend a lot of time in his office late at night, talking about coaching and philosophies and things like that. As the football coach, to extend himself to basketball players and all athletes was extraordinary and beyond the call of duty. Bill thought that when you go to Columbia, you are promised two things: an education and an opportunity. The education you get on your own; it’s up to you to learn what you want to learn. But someone has to help you with the opportunity. Bill was extremely instrumental in getting me my first summer job at Merrill Lynch.” — Gene Schatz ’79 “Bill is inclusive, not exclusive. For example, after his son’s high school football games, he would invite the team for burgers and fries and Cokes at a local restaurant in Palo Alto, Calif., and he would always pick up the tab. At first I said, ‘Come on. Let somebody else pay once in a while.’ He said, ‘No,’ and was emphatic. He said, ‘If one person wouldn’t come to this thing because he couldn’t afford the $10 or $20, I would consider that a failure. I want every kid and his parents to come here and have as many burgers and Cokes as they want, and no one has to worry about whether they can pay. I know that 99 percent of the people can pay, but I don’t want it so one person doesn’t come because he doesn’t have that extra 20 bucks.’ ” — John Cirigliano ’64 “Bill regrets not being able to win as a football coach at Columbia, and I think that is one of the reasons he stays as close to it as he does; he feels like there is some unfinished business, and he wants to see the program succeed. One of the biggest challenges for the athletics department and the football program is, ‘Who is the next Bill Campbell? Who is that guy who cares as much about it as the coaches and the student-athletes and has the wherewithal to make a significant impact?’ That is something people should spend a lot of time on, because Bill is the guy who not only does it, but draws a lot of other people to stay involved.” — Michael Griffin, Columbia associate director of alumni relations “Bill doesn’t preach, and he reads people quickly. It’s easy to think that he is a former football coach who got lucky, but the guy knows Silicon Valley like the back of his hand, and he can convey the stuff to guys with big egos and get them to improve and get the job done.” — Al Butts ’64 “Every person Bill has touched has been empowered [by him] to be the best he or she can be. He is my mentor. I sit with him for an hour a couple of times a month, and in every dimension, whether it is advice about life or growing ventures or serving our community, I count on Bill as a friend and more. They broke the mold when they made him.” — John Doerr, partner at venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caulfield & Byers, Menlo Park, Calif. “We tease him all the time about being the ‘former Columbia coach.’ When I was running the international division of Claris, I would make him come to Europe and meet the press, which he hates to do. I don’t care what country we were in — it could be Finland — inevitably, the article would start, “Former football coach Bill Campbell said, ‘Blah, blah, blah.’ ” I would joke with him relentlessly, ‘I don’t care what you do with your life, you are former football coach Bill Campbell.’” — Donna Dubinsky, cofounder and former CEO, Handspring “Both of us come from backgrounds without any money. Bill comes from a Western Pennsylvania steel town, and I come from Irvington, N.J. Although his father was educated, neither of my parents went to college. So to go to a school like Columbia [Roberta attended Teachers College], well, we didn’t even know people like that existed — the diversity, from all over the world, and certainly from all over the United States. The whole experience was profound for us. The associations we made at Columbia changed our lives and gave us the opportunities that we’ve enjoyed. All of the big opportunities in Bill’s life were the result of knowing someone at Columbia or the education that he received there.” — Roberta Campbell, wife |

| || | || |

CCT Home |

|

|

CCT Masthead |