|

|

|

|

|

FIRST PERSONDocumenting MontgomeryBy Burton Silverman ’49

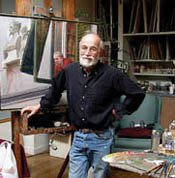

Burton Silverman ’49 in his New York City studio of 36 years in 2004.

Born in Brooklyn in 1928, I rooted for the Dodgers and lived through the Depression with a pampered middle-class obliviousness. I lived through the fight against Nazism that fueled a liberal sensibility in the United States, which had in its recent past been haunted by racism and anti-Semitism. Unfortunately, America has forgotten that, almost 200 years after the beginning of the great democratic experiment, we still excluded women, blacks and other groups from full membership in our society. But despite the progressivism of the ’30s, the optimism of those years came to an end in 1947 when Churchill announced the clang of an Iron Curtain over Europe. This was during my second year at Columbia College, in the wonderful company of vets returning to school under the GI Bill. By this time, I was sure that I was going to be an artist, but unclear about how I would survive as one. After I graduated from the College, I rented a studio with Harvey Dinnerstein, a close artist friend from our time together at Music and Art High School. We were painters until we were drafted into the Korean War in 1951, and America changed again. After we returned in 1953, McCarthyism and fear of the bomb characterized the next decade. I returned to painting and worked part-time in the New York Post promotion department. Then, in December 1955, Rosa Parks made a defiant challenge to segregation. Her now-celebrated refusal to give up her seat on a segregated city bus ignited a boycott by virtually all 50,000 black citizens of Montgomery, Ala. Suddenly, a moral candle glowed in the darkness to affirm the possibility of challenging an unjust social order. When Murray Kempton, a Pulitzer-winning columnist for the New York Post, wrote a series of vivid articles about the boycott, the world took notice.

Silverman’s Woman at Church Rally, 1956; Graphite 8" x 6".

Harvey and I were deeply affected, so much so that he blurted out in the middle of a telephone call about a different subject, “Let’s go there and draw it!” I hesitated for only a moment before saying, “Yeah, let’s.” The boycott had vast social and political implications that were not lost on us, but as artists, Harvey and I also viewed the events in Montgomery from another vantage. We had long identified with an artistic heritage engendered by realists from earlier generations: Goya, Meissonier, Homer and Sargent, all of whom recorded the impact of war on their worlds. The boycott in Montgomery presented an opportunity for us to move beyond a nominal kinship with these artists — to actually record a comparable event — and with the same activity challenge our immediate art world. We felt we had been trivialized because of our unfashionable commitment to realism, and documenting the Montgomery strike was a way out of the exclusion we experienced as a result of the explosion of abstract art. In the end, I think we just wanted to be part of something that said “no” to injustice. In retrospect, this was the setting for one of the most important events in my life. During the seemingly interminable train ride to Montgomery, we realized that as 27-year-old New Yorkers, we hadn’t a clue about the reality of Southern life. Coupled with this awareness came a rising anxiety about whether our drawings would capture the spirit of the protest. We were all but lost for our first 24 hours in Montgomery and can hardly remember where we stayed or what we ate. However, within a day of our arrival, everything came into focus as we sat in on the trial of Martin Luther King Jr. and the other indicted boycott leaders. Seeing our interest, the Montgomery Improvement Association, the African-American labor and activist organization that helped organize the boycott, invited us to attend almost daily church rallies filled with speeches and foot-stomping music. We were swept up by the contagious emotions, and we decided to draw these ordinary citizens, for they were the heart and soul of the protest. This act of youthful impetuousness gave us an extraordinary opportunity to witness and record a historic moment. Our drawings celebrated the ordinary men and women of the cause. Six months later, in September 1956, the Davis Galleries in New York City mounted an exhibition of 90 of these drawings, and several subsequently were reproduced in the New York Post and various magazines. More than half of them were ultimately acquired by the Delaware Art Museum and several others by the Parrish Museum of Art in Southampton, N.Y. The boycott had an important impact on our artistic careers, leading to a lifelong artistic search for similar passions in contemporary life. It influenced our careers as illustrators, as well. Most importantly, the boycott led the way to a more tolerant America and made King the most respected and powerful voice for racial and class justice.

Silverman’s Student Demonstrator Columbia, 1968; Graphite;

In the following months and years, the Civil Rights movement spread throughout the country, and these issues fused with the anti-Vietnam war movement. I was freelancing as an illustrator in 1968 when Columbia students called a strike, deserted classes and occupied campus buildings. New York magazine asked me to do drawings of the demonstrations to illustrate an account written by a student striker. I was back on campus, asked to be a “reporter,” yet drawn into the spirit of the strike as a participant. Because of my drawing abilities, I soon was commissioned by other magazines to report on events using the artist’s eye in place of the camera lens. Drawing for the 1968 strike led, among other assignments, to my making more than 125 portraits across 25 years for the New Yorker’s “Profiles” series. All of them were drawn from life; my subsequent Time and Newsweek covers were not. I regret not having had more of the collegiality at Columbia that was so much a part of my high school days and later professional life. I was a commuter student, and while I was part of campus life as art editor of Jester, I was not quite an imbedded participant. Nevertheless, my College experience provided a richly enhancing intellectual background, and certainly the art history courses of my major were instrumental in shaping my aesthetic philosophy. I remember much that was wonderful, such as teachers like Mark Van Doren, Lionel Trilling ’25, Meyer Schapiro ’24 and Quentin Anderson ’37. And I shared many of the typical student’s passions, such as cheering our heroes Gene Rossides ’49 and Lou Kusserow ’49, who made sports history by beating Army in 1947, and the basketball team that briefly led the Ivies. I also remember the tinge of sadness at graduation of leaving my “home” on the Low Library steps on a sun-drenched June day in 1949. But all I have learned stays with me, and in some sense, informs my current painting. And now the drawings Harvey and I created in 1956 are on display again, this time to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Bus Boycott. They will be on exhibit at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Art until May 26, and again we will celebrate the ordinary men and women who changed the world. Burton Silverman ’49 has had 30 solo shows in the United States and abroad. He has won 33 prizes and awards from some of these exhibitions, and in 2002 received an Honorary Doctorate from the Academy of Art College in San Francisco. His paintings are represented in more than two dozen public collections across the country. Silverman lives and maintains a studio in New York City (www.burtonsilverman.com).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||