|

|

|

|

|

COVER STORY On air, television news correspondent Claire Shipman '86 comes across as soothing, intelligent and alluringly chic. She is, in fact, the popular Midwestern girl with an Ivy League education wrapped in an unrehearsed charm. Many mornings she can be seen on Good Morning America, which she joined last spring as senior national correspondent, a plum position that she earned after a decade in the television trenches. Shipman debuted as a foreign correspondent for CNN, reporting from Russia during the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. From there, she spent two terms covering the Clinton White House for CNN and later NBC, topped off by the extended 2000 presidential campaign. In early 2000, she inspired a network bidding war and emerged as one of ABC's showcased reporters. "She already was a star at NBC, but at ABC, it's official. She has arrived," says Stephanie DeGroote SIPA '88, an ABC News producer in London who was Shipman's graduate school classmate. Shipman says that she "fell into television" while pursuing Russian studies at Columbia. Once having plunged into the industry, however, she rose quickly, making the most of her opportunities to climb within a dozen years from unpaid intern to television personality earning in the neighborhood of $700,000 annually. She has won an Emmy award and two prestigious DuPont broadcasting awards, first for coverage of the 1989 Tiananmen Square uprising in China and then for coverage of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. In 1999, she was honored with Columbia's John Jay Award for professional achievement.

Shipman is one of the most visible female news correspondents, with a reputation for being stylish and articulate. "She's never a TV bunny, and she's not a Beltway bandit," says Carroll Bogert, former Moscow bureau chief for Newsweek, referring to the aggressive Washington, D.C., environment where Shipman works most of the time. "She's serious and credible without seeming out of reach." Shipman is as genteel off-camera as she appears on. In an inherently competitive industry, she has toed to the top without having clawed over potential rivals. She claims that she does lose her temper on occasion, but few can give eyewitness reports. Mostly, she is adored by her colleagues, producers and sources, not to mention by a host of friends whom she has never left behind. "Claire is the whole package. She's kind, loyal, beautiful and smart. There's not too much you can criticize," says Lisa Dallos, a friend who met Shipman when the newswoman first interned at CNN's New York bureau as an undergraduate. Shipman was a semester away from completing her master's at SIPA when she landed a six-month internship working in CNN's Moscow bureau. She couldn't think of a more exciting place to be, in light of her undergraduate studies. There were few signs then that 1989 would be the beginning of the end of the Cold War and that Russia was about to turn into the biggest news story of the last half of the century. In Moscow, Shipman was taken on as a production assistant and never planned to be in front of the camera. When things got busy, she was offered a paid position as a field producer. "Then it was, ‘When the bureau chief is away, can you do some reporting?'" Shipman recalls. One of her first stories was on the opening of the first McDonald's in Moscow. "It was pretty bad from a performance point of view," she says. "The on-air stuff kind of stunned me." In mid-May, Shipman was sent to follow Gorbachev to Beijing just before the Tiananmen Square uprising where she contributed to the network's award-winning coverage. She was scheduled to return to SIPA for the fall semester. "She called after a few months and said, ‘They've offered me a job, but I want to finish my degree,'" recalls Robin Lewis, associate dean at SIPA. "I said, ‘It's a great opportunity. Don't move; we'll place you on leave.'" The calls kept coming every time Shipman got a promotion and the Soviet story got hotter. "It was a fast ascendancy," Lewis notes. "I kept thinking that I should go home, but after two or three years, it was such a good story," Shipman says. "It was so incredible to watch the end of an era and be in a place that I'd studied for so long and to watch it change. First, the early part with Gorbachev and all the excitement, the great days in '89 when the Berlin Wall came down, and then it getting chaotic with the coup and Yeltsin taking over and people ripping down statues of Lenin." Shipman says that her five years in Moscow were the biggest event of her career. "The Lewinsky scandal, the impeachment, the election last fall — they were incredible stories to cover," she says. "Especially with the election, people say, ‘That must have been the most amazing thing you've ever covered,' and I say, ‘No, actually, Moscow was the most amazing.' " "Communism was falling everywhere, and there was a huge buzz," says DeGroote, who was working for ABC News in Moscow. "It was the epicenter of news for a while and the place to be if you were in journalism."

Shipman's future husband, Jay Carney, was reporting from Moscow for Time during that period, although she only met him once, briefly, while there. "There was a real bifurcation there in the press community. There were a lot of older, seasoned journalists who didn't speak Russian, and there was a whole crop of young journalists who were green journalistically but spoke Russian and needed less help to get around," Carney says. "It let us leapfrog up the ladder and end up at a place where there was major news and we worked for major news organizations." Journalists suddenly had access to sources who had been secluded during the Soviet days. "There was this tremendous charge in having access to people who made decisions," Bogert says. "It had never been true in Soviet history and it didn't last. Journalists today have nothing like the access that we had." Not all of the action was in the capital. Shipman covered a broad region and was sent to Afghanistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and the Baltic States, among other places. "We covered everything from conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh — the disputed territory between Armenia and Azerbaijan — to Gorbachev sending tanks into Lithuania to reindeer herders in Siberia," Shipman recalls. "Shipman was covering events that involved violence and instability and were at times dangerous, and she was very calm and cool under fire," says Lewis. A highlight was the 1991 coup against Gorbachev. A week before, Shipman had married CNN bureau chief Steve Hurst. During the coup, she had maneuvered herself inside the Russian White House — one of the few Western journalists there — and she reported live by talking by telephone with Hurst. "I was wandering around, talking to senior aides, watching Yeltsin walking back and forth taking calls from Bush and Thatcher and other foreign leaders," Shipman recalls. She got exclusive interviews with Yeltsin right after the coup, then with Yeltsin and Gorbachev at Christmastime, when Gorbachev resigned and Yeltsin took over. Before leaving Russia at the end of 1993, Shipman covered an aborted coup against Yeltsin in the same fashion, from inside the White House while tanks were firing upon it. While the news stories were sexy, daily living in a country recuperating from nearly 75 years of communism was not. Shipman lived in a relatively comfortable CNN corporate apartment with Hurst, though, which she adorned with Russian antiques and domestic items that she hauled back one suitcase at a time from every trip abroad. Even while working nearly nonstop, she found time to figure out where to get furniture reupholstered or have curtains made in a city with no Yellow Pages and with much worse obstacles. "She knew how to rush around Moscow and get things done Russian-style," says Lewis, who visited Shipman on a few occasions while he was in Moscow. Russia also was the beginning of Shipman's reputation for gracious and lively entertaining, her apartment becoming a virtual hospitality suite for ex-pats. "It seems like I was always being fed and watered at their place," DeGroote says. Shipman did this not only in Moscow, but at the couple's rented countryside dacha. "It was a real social hub, like a literati," DeGroote says of the summer house and its guests. "People were coming and going, wine was flowing and there were intense conversations about this and that. High-powered politicians, top-level journalists, filmmakers, young American entrepreneurs — it seemed everyone who was interesting would come through their place at one point." All the time Shipman was cultivating this new social circle, she maintained one across the Atlantic. At her Moscow wedding, Bogert was struck by how many of her friends from home had made the journey to celebrate the event. "It's easy to let relationships lapse, but she's a gardener. She's keeping plants alive all over the place," she says. At the end of 1993, after five years in Russia, Shipman returned home. She insisted that CNN give her six months between assignments so that she could return to SIPA and finish her degree, which she did. From the time she was an undergraduate, Shipman has had an affection for Morningside Heights. "There's something about Columbia I really love," she says. "I love the feeling of the buildings on campus and the possibilities of it all and being surrounded by all that excellence all the time. I found it very exciting."

Shipman's route to Columbia was a circuitous one, as she joked when she returned to campus to deliver the Class Day address in 1999. She spent single semesters at Ohio State, UC Berkeley and the University of Michigan before applying to Columbia, coincidentally the first year that it was accepting applications from women. Because she came in as a sophomore, Shipman graduated in 1986, ahead of the first official graduating class that included women. Although while growing up in Columbus, Ohio, she ran with the popular crowd, by the time Shipman settled at Columbia, she focused on her studies and was not very involved with nonacademic campus life. "I think I spent more time with my professors than with other students," she says. "My husband is always teasing me that I was such a goody two-shoes." Learning to speak Russian and completing the requirements for that major occupied a good portion of her time. She would steal over to the Harriman Institute for its programs and to watch the Soviet television feed. At that same time, Carney was similarly immersed in Russian studies as an undergraduate at Yale. "It's funny because I came very close to going to Columbia and we would have been there at the same time," he says. When Shipman relocated to Washington after finishing at SIPA in mid-1994, she encountered Carney again on the White House beat, which he was covering for Time. When the two had first met, on Red Square, they did not hit it off, but this time they commiserated about their Russia experiences and became friends. "He was really nice and sweet and helped me break into the beat, so I saw his good side," Shipman says. Carney went out of his way to help Shipman get acclimated. "Washington journalism is very different than doing a story abroad," Carney says. "It's all about who you know. It's access journalism and much more complicated." In 1996, Shipman separated from Hurst, and Carney embarked on a long road to persuading her to go out with him. She gave in, and friends say it was one of the best moves she has made. They were married just after the Ken Starr report to Congress in 1999, and on October 15, 2001, they had their first child, red-haired Hugo James Carney. The two have never been directly competitive, because even when they were covering the White House, Shipman's day revolved around getting breaking news on television while Carney worked for a weekly news magazine. Now that they're married, she reads his pieces in Time religiously, and he sets his alarm clock to watch her on Good Morning America. They often speak Russian — at home to keep up their practice and in public for privacy. The couple doesn't avoid bringing work home. "You understand what the other person is going through, but sometimes you end up living your job so much. Because we're doing such similar things, it can be hard to escape," Shipman says. When one of Shipman's sources called her during the night to tell her that Al Gore's runningmate would be Senator Joseph Lieberman, giving Shipman one of her bigger scoops of the campaign, Carney was right next to her but says he never would have thought of using it. In addition to writing for Time, Carney appears regularly as a guest on CNN Inside Politics, The McLaughlin Group, The Charlie Rose Show and Hardball. "I'll have feelings of being really proud and a little envious if he has a great story," Shipman says. "But it's always pride first." Friends say Shipman never forgets anyone's birthday. Even during the crazy pace of last year's campaign trail covering Gore, she would remind her producer of crew members' birthdays and arrange for a cake. "That's how you should treat people, and it's so unexpected in our business," says Dan Erlenborn, the NBC producer who was paired with Shipman during the campaign.

Shipman's affability, as well as her ability to actively cultivate the little people as well as the big shots, undoubtedly enhances her reporting. "When you're out in the field interviewing people, it helps if you can relate to them and not be coming at them from an ivory tower or putting them off," says Andrea Mitchell, chief foreign affairs correspondent for NBC. "Claire really likes people." Early in last year's presidential campaign, Shipman was able to get an exclusive interview with the Gore family — including the candidate's mother, who rarely does interviews — at the family farm. NBC sent three crews and spent the day there dashing around with Shipman. But it didn't end when the cameras were turned off. "Then the vice president said, ‘We're cooking burgers here. Why don't you stay?'" Erlenborn recounts. "We stayed until 11 p.m. I guarantee they wouldn't have done that for Sam Donaldson!" "It's Claire's nature that got her where she is today," Erlenborn adds. "She's unrelenting, yet so pleasant that people have trouble saying no to her." Yet as wide as her sources are and as skilled a reporter as she is, Shipman still feels the burn of self-criticism. "You go out to the White House lawn to do your piece and you get in you ear, ‘Why is CBS reporting...?' Or you read the paper and wonder, ‘Why didn't I have that detail?' It's a lot of second-guessing. I'm confident in what I do, but I'm conscious of the potential to goof it up. I tend to feel that I never have enough time to prepare. I could spend days preparing, which would be a little obsessive, so it's probably good that I'm in the daily business." Case in point: While Shipman was writing columns for George magazine, she would pore over them for days and then ask Carney to edit them, conscious that "print stays around forever compared to television," she says. "She's a real perfectionist," Carney says. "She's very hard on herself and always wants to do better." After reading the news one morning as the substitute news anchor on Good Morning America, she inspects the rerun on the monitor in her dressing room. "I hate watching myself. I'm not a natural ham," she says. "I'd rather just do it and not look at it, but then you don't learn anything." She is also famously fastidious about her appearance, a preoccupation that goes back to her high school days. She's not a work-out devotee, yet she manages to stay trim despite an insatiable appetite for ice cream. She's known for her jammed closets, and for pulling endless new outfits out of a garment bag on road trips. Her smooth brown hair, doe-like eyes and soft peach complexion are accented by all the right jewelry and makeup, although she won't be seen preening, making her polished appearance seem effortless. Shipman spent more than six years working for CNN and then for NBC on the White House beat, which is notorious for being physically and mentally grueling. Her day sometimes started at 3 a.m. and she was ready to go live with news by 5 a.m. The press corps spends its days crammed into tiny cubicles in the windowless press room in the West Wing, emerging only to go on camera or to attend briefings in a low-ceilinged room that was an indoor swimming pool before President Nixon had it converted to the "press pool." "It was hard. I'd never thought about covering politics. At least with Russia, I had studied it," Shipman says. "With the White House, you're expected to be up to date about everything from budget deals to Social Security to the politics of Iowa to what Milosevic is doing." The Lewinsky scandal, which dragged on for more than a year, was a low point that Shipman describes as one of her most difficult times as a reporter. "There was a feeling of, ‘Are we going out on a brink, and are we ever going to get back?'" she says. "Especially because we weren't hearing from the president anything resembling the truth. The pressure to be first with things or match what other news organizations had — I've never felt that kind of pressure. You would feel a sense of failure if you didn't have what someone else had and yet doubt if it was even true." "It was very tough for anyone covering it, especially for women," NBC's Andrea Mitchell says. "The subject was so distasteful. It wasn't like covering a foreign policy issue. But she handled it brilliantly." At times Shipman's probing questions irritated Clinton, as when halfway through the scandal she asked if the president planned to help pay the legal bills of those called before the Grand Jury, as he had done for colleagues called to testify about Whitewater. Another test of stamina was the marathon Bush-Gore presidential race, the pace of which was exhausting. "With NBC, you have this insatiable beast to satisfy," the producer Erlenborn explains. "Claire would get up at 5 or 4 or sometimes 3 a.m., depending on which coast we were on. Most mornings, [radio talk show host Don] Imus would call, and she'd talk to him from her hotel room while putting on her makeup. We did a live shot for the morning news, then MSNBC would call asking for a 9 a.m. and 10 a.m. shot. Then we had another show on CNBC at 6 p.m., a half-hour before Nightly News. A lot of times, they wanted her to do that live, and then it didn't stop with Nightly. The Brian Williams Show would be calling to do its 9 p.m. show. Sometimes she also did Geraldo or Hardball — it was a never-ending cycle. A lesser person would have crumbled, but she plowed through it and never complained." Mitchell says Shipman always kept her sense of humor, even in challenging working conditions at the political conventions. "You're in this boiler room atmosphere in the basement of the convention hall trying to broadcast in the middle of a screaming mob, juggling this crazy technology and the ear pieces and not being able to hear and trying to get your stories out, and Claire was always very collected and immaculate and under control," Mitchell says. At the end of the campaign tunnel, when Shipman and everyone else had vacations planned and internal timers set to celebrate, came the election night zinger. The timers went off but work was as hectic as ever and vacations were canceled. "Nobody knew how or when it was going to end, or if it was going to end," Erlenborn says. "You could see that Claire was a little more irritable, but I never saw her raise her voice or snap at people. You could just sense not to ask her anything else. That's the extent I've seen any crossness." One of Shipman's biggest scoops came when she went live and announced — before the official announcement — the Florida Supreme Court decision that ballot recounts could continue. Breaking that story, the Lieberman one and others surely helped Shipman's bargaining position when ABC moved to lure her away from NBC. "I wanted to do something different and NBC was great about trying to find something for me, but they didn't have this exact job," Shipman says.

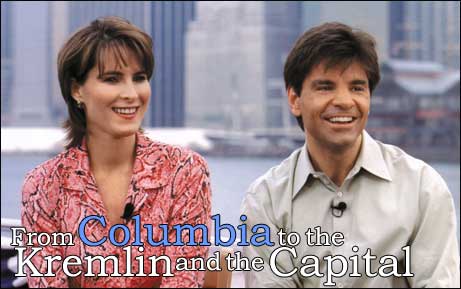

At ABC, instead of having a regular beat and a regular schedule, Shipman is essentially a roving reporter who pitches stories on whatever she wants, appears live on Good Morning America two to three times a week, will do some reports for This Week on Sunday and have some anchoring opportunities for the Good Morning America newscast and the weekend editions of World News Tonight. In her first months on the job, Shipman got an exclusive interview with President Bush at the time of his decision on stem cell research funding; did extensive profiles on Bush's counselor, Karen Hughes, and Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge, head of the Office of Homeland Security; and put together a long Nightline piece on the president's first week following the September 11 terrorist attacks. Shipman also regularly works with political adviser turned television commentator and correspondent George Stephanopoulos '82. The two have teamed up for reports on the gap between the rich and poor in New York City, the stem cell research debate, Vice President Richard Cheney's energy plan and the Patients' Bill of Rights, among others. While she was happy at NBC, Shipman says her current position is her dream job. "I do mainly what I like to do — a lot of profiles of people, longer pieces. I get intrigued by people and figuring out what makes them tick. It's great because with the morning show, I still get pulled into the daily news. And with the Sunday show, I still get to do my political junkie thing." "Claire is one of those people who from the first time I met her I knew she was going to do something, and she has," DeGroote says. "And she has done it with grace and style and hasn't pissed anyone off, which in this business is no small feat." About the Author: Shira J. Boss '93 is a contributing writer whose last cover story for CCT was "Technology and Columbia: A Digital Revolution," a two-part series that ran in December 2000 and February 2001.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Claire Shipman '86 has been at the center of news in Moscow

and Washington and is now one of the most visible correspondents in

television

Claire Shipman '86 has been at the center of news in Moscow

and Washington and is now one of the most visible correspondents in

television