|

|

|

|

|

COLUMBIA FORUMPicasso of the KitchenAuguste Escoffier and The Essence of TasteBy Jonah Lehrer ’03So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and warmth and the love of it and the hunger for it ... and then the warmth and richness and fine reality of hunger satisfied ... and it is all one. —M.F.K. Fisher,

Jonah Lehrer ’03 PHOTO: LORI DUFF In his well-received first book, Proust Was A Neuroscientist, Jonah Lehrer ’03, a Rhodes Scholar, argues that science alone cannot map out all the mysteries of the brain. Artists such as Proust and Woolf, with their exquisite intuition and penchant for self-study, have foretold the mind’s workings in ways that modern neuroscience would only later confirm. “This book is about artists who anticipated the discoveries of neuroscience,” writes Lehrer. “It is about writers and painters and composers who discovered truths about the human mind — real, tangible truths — that science is only now rediscovering. Their imaginations foretold the facts of the future.” In this chapter from Proust Was A Neuroscientist, Lehrer, who has worked in the kitchens of Le Cirque 2000 and Le Bernardin, looks at the discoveries of a culinary artist, the French chef Auguste Escoffier.

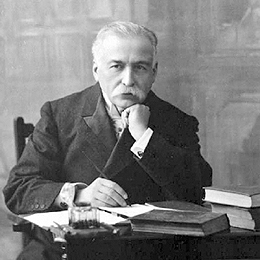

For Escoffier, cooking was a matter of obeying the whims of your senses. It was hedonism, not a science experiment, so pleasure was your guide. Photo © Foundation Auguste Escoffier-Villeneuve Loubet, France (06)  Auguste Escoffier invented veal stock. Others had boiled bones before, but no one had codified the recipe. Before Escoffier, the best way to make veal stock was cloaked in mystery; cooking was like alchemy, a semimystical endeavor. But Escoffier came of age during the late stages of positivism, a time when knowledge — some of it true, some of it false — was disseminated at a dizzying rate. Encyclopedias were the books of the day. Escoffier took this scientific ethos to heart; he wanted to do for fancy food what Lavoisier had done for chemistry, and replace the old superstitions of the kitchen with a new science of cooking. At the heart of Escoffier’s insight (and the source of more than a few heart failures) was his use of stock. He put it in everything. He reduced it to gelatinous jelly, made it the base of pureed soups, and enriched it with butter and booze for sauces. While French women had created homemade stock for centuries — pot-au-feu (beef boiled in water) was practically the national dish — Escoffier gave their protein broth a professional flair. In the first chapter of his Guide Culinaire (1903), Escoffier lectured cooks on the importance of extracting flavor from bones: “Indeed, stock is everything in cooking. Without it, nothing can be done. If one’s stock is good, what remains of the work is easy; if, on the other hand, it is bad or merely mediocre, it is quite hopeless to expect anything approaching a satisfactory meal.” What every other chef was throwing away — the scraps of tendon and oxtail, the tops of celery, the ends of onion, and the irregular corners of carrot — Escoffier was simmering into sublimity.

In his kitchen, a proper cook was a man of exquisite sensitivity, “carefully studying the trifling details of each separate flavor before he sends his masterpiece of culinary art before his patrons.”  Although Escoffier introduced his Guide Culinaire with the lofty claim that his recipes were “based upon the modern science of gastronomy,” in reality he ignored modern science. At the time, scientists were trying to create a prissy nouvelle cuisine based on their odd, and totally incorrect, notions of what was healthy. Pig blood was good for you. So was tripe. Broccoli, on the other hand, caused indigestion. The same with peaches and garlic. Escoffier ignored this bad science (he invented peach Melba), and sautéed away to his heart’s malcontent, trusting the pleasures of his tongue over the abstractions of theory. He believed that the greatest threat to public health was the modern transformation of dining from a “pleasurable occasion into an unnecessary chore.” The form of Escoffier’s encyclopedic cookbook reflects his romantic bent. Although he was fond of calling sauciers (the cooks responsible for making the sauces) “enlightened chemists,” his actual recipes rarely specify quantities of butter or flour or truffles or salt. Instead, they are descriptions of his cooking process: melt the fat, add the meat, listen “for the sound of crackling,” pour in the stock, and reduce. It sounds so easy: all you have to do is obey the whims of your senses. This isn’t a science experiment, Escoffier seems to be saying, this is hedonism. Let pleasure be your guide. Escoffier’s emphasis on the tongue was the source of his culinary revolution. In his kitchen, a proper cook was a man of exquisite sensitivity, “carefully studying the trifling details of each separate flavor before he sends his masterpiece of culinary art before his patrons.” Escoffier’s cookbook warns again and again that the experience of the dish — what it actually tastes like — is the only thing that matters: “Experience alone can guide the cook.” A chef must be that artist on whom no taste is lost. But Escoffier knew that he couldn’t just serve up some grilled meat and call it a day. His hedonism had to taste haute. After all, he was a chef in the hotels of César Ritz, and his customers expected their food to be worthy of the gilded surroundings and astonishing expense. This is where Escoffier turned to his precious collection of stocks. He used his stocks to ennoble the ordinary sauté, to give the dish a depth and density of flavor. After the meat was cooked in the hot pan (Escoffier preferred a heavy, flat-bottomed poele), the meat was taken out to rest, and the dirty pan, full of delicious grease and meat scraps, was deglazed. * Escoffier would also use wine, brandy, port, wine vinegar, and — if there was no spare booze lying around — water. Deglazing was the secret of Escoffier’s success. The process itself is extremely simple: a piece of meat is cooked a very high temperature — to produce a nice seared Maillard crust, a cross-linking and caramelizing of amino acids — and then a liquid, such as a rich veal stock, is added.* As the liquid evaporates, it loosens the fronde, the burned bits of protein stuck to the bottom of the pan (deglazing also makes life easier for the dishwasher). The dissolved fronde is what gives Escoffier’s sauces their divine depth; it’s what makes beef bourguignon, bourguignon. A little butter is added for varnish, and voilà! the sauce is complet. Menu Served to Emperor Wilhelm II Hors-d’oeuvre Suédois

Suprêmes de Sole au Vin du Rhin

Selle de Mouton de Pré-salé aux Laitues à la Grecque Poularde au Paprika Rose Gelée au Champagne Cailles aux Raisins Asperges Sauce Mousseline Soufflé Surprise Fruits Café Mode Orientale Vins: Eitchbacher 1897 The Secret of DeliciousnessEscoffier’s basic technique is still indispensable. Few other cultural forms have survived the twentieth century so intact. Just about every fancy restaurant still serves up variations of his dishes, recycling their bones and vegetable tops into meat stocks. From espagnole sauce to sole Véronique, we eat the way he told us to eat. And since what Brillat-Savarin said is probably true — “The discovery of a new dish does more for the happiness of the human race than the discovery of a new star” — it is hard to overestimate Escoffier’s importance. Clearly, there is something about his culinary method — about stocks and deglazing and those last-minute swirls of butter — that makes some primal part of us very, very happy. The place to begin looking for Escoffier’s ingenuity is in his cookbooks. The first recipe he gives us is for brown stock (estouffade), which he says is “the humble foundation for all that follows.” Escoffier begins with the browning of beef and veal bones in the oven. Then, says Escoffier, fry a carrot and an onion in a stockpot. Add cold water, your baked bones, a little pork rind, and a bouquet garni of parsley, thyme, bay leaf, and a clove of garlic. Simmer gently for twelve hours, making sure to keep the water at a constant level. Once the bones have given up their secrets, sauté some meat scraps in hot fat in a saucepan. Deglaze with your bone water and reduce. Repeat. Do it yet again. Then slowly add the remainder of your stock. Carefully skim off the fat (a stock should be virtually fat-free) and simmer for a few more hours. Strain through a fine chinois. After a full day of stock-making, you are now ready to start cooking. In Escoffier’s labor-intensive recipe, there seems to be little to interest the tongue. After all, everybody knows that the tongue can taste only four flavors: sweet, salty, bitter and sour. Escoffier’s recipe for stock seems to deliberately avoid adding any of these tastes. It contains very little sugar, salt or acid, and unless one burns the bones (not recommended), there is no bitterness, Why, then, is stock so essential? Why is it the “mother” of Escoffier’s cuisine? What do we sense when we eat a profound beef daube, its deglazed bits simmered in stock until the sinewy meat is fit for a spoon? Or, for that matter, when we slurp a bowl of chicken soup, which is just another name for chicken stock? What is it about denatured protein (denaturing is what happens to meat and bones when you cook them Escoffier’s way) that we find so inexplicably appealing? The answer is umami, the Japanese word for “delicious.” Umami is what you taste when you eat everything from steak to soy sauce. It’s what makes stock more than dirty water and deglazing the essential process of French cooking. To be precise, umami is actually the taste of L-glutamate (C5H9NO4), the dominant amino acid in the composition of life L-glutamate is released from life-forms by proteolysis (a shy scientific word for death, rot and the cooking process). While scientists were still theorizing about the health benefits of tripe, Escoffier was busy learning how we taste food. His genius was getting as much L-glutamate on the plate as possible. The emulsified butter didn’t hurt either. The story of umami begins at about the same time Escoffier invented tournedos Rossini, a filet mignon served with foie gras and sauced with a reduced veal stock and a scattering of black truffles. The year was 1907, and Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda asked himself a simple question: What does dashi taste like? Dashi is a classic Japanese broth made from kombu, a dried form of kelp. Since at least A.D. 797, dashi has been used in Japanese cooking the same way Escoffier used stock, as a universal solvent, a base for every dish. But to Ikeda, the dashi his wife cooked for him every night didn’t taste like any of the four classic tastes or even like some unique combination of them. It was simply delicious. Or, as the Japanese would say, it was umami. And so Ikeda began his quixotic quest for this unknown taste. He distilled fields of seaweed, searching for the essence that might trigger the same mysterious sensation as a steaming bowl of seaweed broth. He also explored other cuisines. “There is a taste,” Ikeda declared, “which is common to asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat but which is not one of the four well-known tastes.” Finally, after patient years of lonely chemistry, during which he tried to distill the secret ingredient that dashi and veal stock had in common, Ikeda found his secret molecule. It was glutamic acid, the precursor of L-glutamate. He announced his discovery in the Journal of the of Chemical Society of Tokyo.

While scientists were still theorizing about the health benefits of tripe, Escoffier was busy learning how we taste food.  Glutamic acid is itself tasteless. Only when the protein is broken down by cooking, fermentation, or a little ripening in the sun does the molecule degenerate into L-glutamate, an amino acid that the tongue can taste. “This study has discovered two facts,” Ikeda wrote in his conclusion, “one is that the broth of seaweed contains glutamate and the other that glutamate causes the taste sensation ‘umami.’” But Ikeda stlll had a problem. Glutamate is an unstable molecule, eager to meld itself to a range of other chemicals, most of which are decidedly not delicious. Ikeda knew that he had to bind glutamate to a stable molecule that the tongue did enjoy. His ingenious solution? Salt. After a few years of patient experimentation, Ikeda was able to distill a metallic salt from brown kelp. The chemical acronym of this odorless white powder was MSG, or monosodium glutamate. It was salty, but not like salt. It also wasn’t sweet, sour or bitter. But it sure was delicious. Ikeda’s research, although a seminal finding in the physiology of taste, was completely ignored. Science thought it had the tongue solved. Ever since Democritus hypothesized in the fourth century B.C. that the sensation of taste was an effect of the shape of food particles, the tongue has been seen as a simple muscle. Sweet things, according to Democritus, were “round and large in their atoms,” while “the astringently sour is that which is large in its atoms but rough, angular and not spherical.” Saltiness was caused by isosceles atoms, while bitterness was “spherical, smooth, scalene and small.” Plato believed Democritus, and wrote in Timaeus that differences in taste were caused by atoms on the tongue entering the small veins that traveled to the heart. Aristotle, in turn, believed Plato. In De Anima, the four primary tastes Aristotle described were the already classic sweet, sour, salty and bitter. Over the ensuing millennia, this ancient theory remained largely unquestioned. The tongue was seen as a mechanical organ in which the qualities of foods were impressed upon its papillaed surface. The discovery of taste buds in the nineteenth century gave new credence to this theory. Under a microscope, these cells looked like little keyholes into which our chewed food might fit, thus triggering a taste sensation. By the start of the twentieth century, scientists were beginning to map the tongue, assigning each of the four flavors to a specific area. The tip of the tongue loved sweet things, while the sides preferred Sour. The back of the tongue was sensitive to bitter flavors, and saltiness was sensed everywhere. The sensation of taste was that simple. * MSG is often blamed for the so-called Chinese Restaurant Syndrome, in which exposure to MSG is thought to cause headaches and migraines in certain individuals. But as Jeffrey Steingarten has noted (It Must’ve Been Something I Ate, pp. 85-99), recent research has exonerated both Chinese food and MSG. Unfortunately for Ikeda, there seemed to be no space left on the tongue for his delicious flavor. Umami, these Western scientists said, was an idle theory unique to Japanese food, a silly idea concerned with something called deliciousness, whatever that was. And so while cooks the world over continued to base entire cuisines on dashi, Parmesan cheese, tomato sauce, meat stock and soy sauce (all potent sources of L-glutamate), science persisted in its naïve and unscientific belief in four, and only four, tastes.

In fact, we are trained from birth to savor umami: breast milk has ten times more glutamate than cow milk.  Despite the willful ignorance of science, Ikeda’s idea gained a certain cult following. His salty white substance, MSG, a powder that science said couldn’t work because we had no means to taste it, nevertheless became an overused staple in everything from cheap Chinese food to bouillon cubes, which used glutamate to simulate the taste of real stock. MSG was even sold in America under the labels Super Seasoning and Accent.* As food products became ever more processed and industrial, adding a dash of MSG became an easy way to create the illusion of flavor. A dish cooked in the microwave tasted as if it had been simmered for hours on the stovetop. Besides, who had time to make meat stock from scratch? * Embarrassed food manufacturers often hide the addition of MSG by calling it autolyzed yeast extract on their labels (other pseudonyms for MSG include glutavene, calcium caseinate, and sodium caseinate). With time, other pioneers began investigating their local cuisines and found their own densities of L-glutamate. Everything from aged cheese to ketchup was rich in this magic little amino acid. Umami even seemed to explain some of the more perplexing idiosyncrasies of the cooking world: why do so many cultures, beginning with ancient Rome, have a fish sauce? (Salted, slightly rotting anchovies are like glutamate speedballs. They are pure umami.) Why do we dip sushi in soy sauce? (The raw fish, being raw, is low in umami, since its glutamate is not yet unraveled. A touch of soy sauce gives the tongue the burst of umami that we crave.) Umami even explains (although it doesn’t excuse) Marmite, the British spread made of yeast extract, * which is just another name for L-glutamate. (Marmite has more than 1750 mg of glutamate per 100 g, giving it a higher concentration of glutamate than any other manufactured product.) Of course, umami is also the reason that meat — which is nothing but amino acid — tastes so darn good. If cooked properly, the glutamate in meat is converted into its free form and can then be tasted. This also applies to cured meats and cheeses. As a leg of prosciutto ages, the amino acid that increases the most is glutamate. Parmesan, meanwhile, is one of the most concentrated forms of glutamate, weighing in at more than 1200 mg per 100 g. (Only Roquefort cheese has more.) When we add an aged cheese to a pasta, the umami in the cheese somehow exaggerates the umami present elsewhere in the dish. (This is why tomato sauce and Parmesan are such a perfect pair. The cheese makes the tomatoes more tomatolike.) A little umami goes a long way. And of course, umami also explains Escoffier’s genius. The burned bits of meat in the bottom of a pan are unraveled protein, rich in L-glutamate. Dissolved in the stock, which is little more than umami water, these browned scraps fill your mouth with a deep sense of deliciousness, the profound taste of life in a state of decay. The culture of the kitchen articulated a biological truth of the tongue long before science did because it was forced to feed us. For the ambitious Escoffier, the tongue was a practical problem, and understanding how it worked was a necessary part of creating delicious dishes. Each dinner menu was a new experiment, a way of empirically verifying his culinary instincts. In his cookbook, he wrote down what every home cook already knew. Protein tastes good, especially when it’s been broken apart. Aged cheese isn’t just rotten milk. Bones contain flavor. But despite the abundance of experiential evidence, experimental science continued to deny umami’s reality. The deliciousness of a stock, said these haughty lab coats, was all in our imagination. The tongue couldn’t taste it. Chicken Breasts with OystersSuprêmes de Volaille aux HuitresLift out the suprêmes of the two small chickens; poach them in butter and lemon juice, and coat them with Suprême Sauce. Arrange them around a low, very cold bed of bread, placed on the dish at the last moment. Upon this bed, quickly set a dozen shucked oysters, which should have been kept in ice for at least two hours. Serve very quickly in order that the suprêmes may be very hot and the oysters very cold. Send a Suprême sauce separately. What Ikeda needed before science would believe him was anatomical evidence that we could actually taste glutamate. Anecdotal data from cookbooks, as well as all those people who added fish sauce to their pho, Parmesan to their pasta, and soy sauce to their sushi, wasn’t enough. Finally, more than ninety years after Ikeda first distilled MSG from seaweed, his theory was unequivocally confirmed. Molecular biologists discovered two distinct receptors on the tongue that sense only glutamate and L-amino acids. In honor of Ikeda, they were named the umami receptors. The first receptor was discovered in 2000, when a team of scientists noticed that the tongue contains a modified form of a glutamate receptor already identified in neurons in the brain (glutamate is also a neurotransmitter). The second occurred in 2002, when another umami receptor was identified, this one a derivative of our sweet taste receptors.* Supreme SauceSauce SuprêmeThe salient characteristics of Suprême sauce are its perfect whiteness and delicacy. It is generally prepared in small quantities only. Preparation — Put 11–2 pints of very clear poultry stock and one-quarter pint of mushroom cooking liquor into a saucepan. Reduce to two-thirds; add one pint of “poultry velouté;” reduce on an open fire, stirring with the spatula, and combine one-half pint of excellent cream with the sauce, this last ingredient being added little by little. When the sauce has reached the desired consistency, strain it through a sieve, and add another one-quarter pint of cream and two oz. of best butter. Stir with a spoon, from time to time, or keep the pan well covered. These two separate discoveries of umami receptors on the tongue demonstrated once and for all that umami is not a figment of a hedonist’s imagination. We actually have a sense that responds only to a veal stock, steak and dashi. Furthermore, as Ikeda insisted, the tongue uses the taste of umami as its definition of deliciousness. Unlike the tastes of sweet, sour, bitter and salty, which are sensed relative to one another (this is why a touch of salt is always added to chocolate, and why melon is gussied up with ham), umami is sensed all by itself. It is that important. This, of course, is perfectly logical. Why wouldn’t we have a specific taste for protein? We love the flavor of denatured protein because, being protein and water ourselves, we need it. Our human body produces more than forty grams of glutamate a day, so we constantly crave an amino acid refill. (Species that are naturally vegetarian find the taste of umami repellent. Unfortunately for vegans, humans are omnivores.) In fact, we are trained from birth to savor umami: breast milk has ten times more glutamate than cow milk. The tongue loves what the body needs. Excerpted from Proust Was A Neuroscientist by Jonah Lehrer. Copyright © 2007 by Jonah Lehrer. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Recipes reprinted from The Escoffier Cookbook. Copyright © 1969 by Crown Publishers. Published by Crown Publishers, a division of Random House Inc.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||