Presenting the winners of our first personal essay contest.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Presenting the winners of our first personal essay contest.

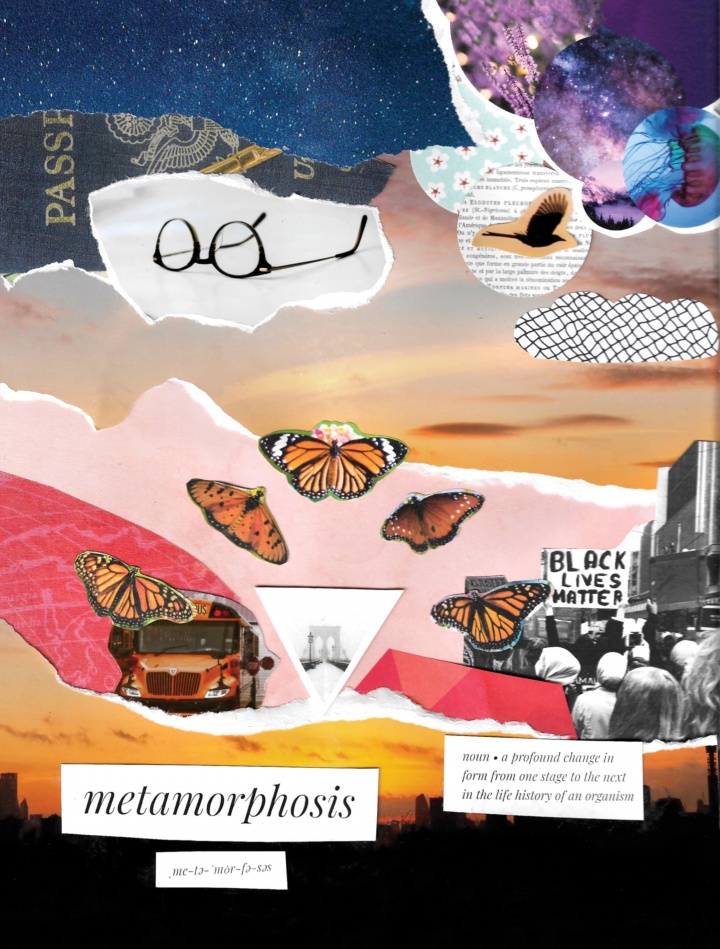

Moving forward with our theme — we knew Ovid would approve — we put out the call to alumni and students. We weren’t so much seeking neat conclusions as honest attempts at reflection (it helps to remember that one definition of essay is “to try”). We were pleased to have so many writers rise to the challenge. Contributors opened up about family, race, sexuality and identity; they also mused on everyday experiences that, upon closer inspection, revealed hidden depths.

Our winners — Amanda Tien ’14 and Munirat Suleiman ’24 — both tell powerful personal stories. Their writing styles differ, but they share a common beauty and bravery. And each of their essays carries extra resonance at this particular moment in our cultural and pandemic life. I’ll let you read on to see why.

No account of the contest would be complete without a thank-you to our judges: Helena Andrews-Dyer ’02, a Washington Post reporter and author of Reclaiming Her Time: The Power of Maxine Waters; Robert Kolker ’91, a journalist and the bestselling author of Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family, a Top Ten Book of 2020 for The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal; and Miya Matsumoto Lee ’18, editor of Modern Love Projects at the Times and co-editor of Tiny Love Stories: True Tales of Love in 100 Words or Less. The three gave generously of their time and brought tremendous care and sensitivity to the deliberations. They were impressed with the skills brought to the winning essays, as well as the emotion each writer conveyed.

The judges also awarded two honorable mentions, to James Vasco Rodrigues ’15, SOA’20 and Abigail Peters ’22. You can find those published online in our Feature Extras.

Thank you to everyone who contributed and fearlessly brought something personal to the page. As Ovid said: “Be patient and tough; one day this pain will be useful to you.”

— Alexis Boncy SOA’11

By Amanda Tien’14

One hazy August afternoon, golden sun flooding the Virginia backroads to my parents’ house, I realized as I drove that I could no longer read the street signs. I pulled over and held my right palm over one eye, then the other, imitating the optometrist appointments I’d gone to for most of my life. At home, I held my shame and fear all through dinner, then pulled my mom aside and said, “I don’t think I should drive anymore.”

Our optometrist confirmed my vision had degraded significantly, but he didn’t know why. He referred us to an ophthalmologist. We were an Army family; our insurance was limited to military facilities. The nearest one? The (in)famous, depending on who you ask, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

My mother drove us on the Capital Beltway, a massive interchange of highway. She swiftly charted the concrete seas out of the woods of northern Virginia, bypassed the stone monument mountains of D.C. and led us to the milky waters of Maryland.

At Walter Reed, we sat on metal chairs with geometric-patterned cushions, waiting long past our appointment time. Polite, quiet soldiers sat nearby, one with dark glasses, another with a thick head bandage. My mother gripped my hand tightly. She pressed play on an iPod audiobook of Pride and Prejudice for me, and I remembered how much I used to love reading for fun. She flipped through a military magazine with articles about moving dogs abroad and making neighborhood casseroles.

When I entered the exam room, the young doctor stared, open-mouthed, for a few awkward moments. I clearly was not who he had expected. We did the classic test; no, I couldn’t read most of the rows. No, not better one, better two. He brought in the attending, a middle-aged woman who shined a bright penlight into my eye. It hurt, searing on a hyper channel to the back of my brain.

She asked, “Did you pour acid in your eye?”

My mom guffawed from the corner.

“Uh, no,” I said, awkward and 19, “I didn’t.”

“Not in chem lab, or something?” he asked.

I shook my head. “I’m not in classes like that. I’m a film major.” They looked at each other and didn’t say anything.

Soon, the room was filled with medical students and doctors. Each one shined the same painful light in my eyes. They clustered in the hallway, whispering. I was relegated to picking up not-great phrases:

“Wow, weird.”

“Her cornea, it’s disintegrating.” (I took AP bio, remembered enough to know this wasn’t good.)

“You sure she wasn’t in an acid attack? Because it looks like it could be an acid attack.”

“She’s in college, not a war zone in the Middle East.” “I don’t know.” “He doesn’t know.” “No one knows.”

I went home with no answers and an appointment for a month later. I would be back at Columbia for my sophomore year by then, unless I took a health leave of absence.

I didn’t want to do that. It wasn’t that bad, I told myself. It would be fine. I would be fine.

I went back to school. It was not fine. As the weeks of fall semester passed, the omnipresent laptop screen burned more and more painfully into my retinas. My headache was constant. The smoke of New York (cigarettes outside campus buildings, blustery gusts from street vendors, a fire drifting its essence over the avenues) was unavoidable and delivered agonizing hazes. One eye worsened faster; my depth perception evaporated. I knocked over cups and cups of coffee. I did fine speaking aloud in Italian class, but when I tried to do my written homework, the language felt even more impossible to parse, my gaze shifting in and out of focus without my control. The beautiful campus I loved was shrouded; I told my mother that it was as if my eyes were becoming panes of frosted glass.

A month later, I took the Amtrak Northeast Regional to D.C. The exam was repeated. The Walter Reed doctors made one statement with assuredness: I was legally blind.

I cried in the car. My mother’s voice was timid with pity. She offered to fill my new prescription at the LensCrafters in the mall — frames from the expensive section, Plexiglass-encased from us dirty-fingered plebes. The glasses themselves were a desperate rope for the sinking ship of my vision.

The fear of a forever night eclipsed every day.

My academic advisor asked, “If this is the last year you can see, what do you want to do with that time?” A childhood dream flashed: novelist. There were fiction workshops at Columbia; Beginning was consistently full, Intermediate required applications. Fear always held me back. I was sure I had missed my chance at ever joining the department. I gently tucked the dream away again.

Professors were supportive. They didn’t comment when I wore the eye patch I bought from Duane Reade. Disability Services gave me a computer program that turned any text into an audiobook, which felt vaguely illegal. I wondered if it was too late in the game to learn Braille.

One day, my mother got a call from Walter Reed; they wanted me to come back.

Again, I took the train, and again, my mother drove. She found small things that made our strange routine special: a kiosk on a floor frequented by nurses who smiled at me and called me pretty; lattes and muffins, banana nut for her, blueberry for me.

This time, we did not wait. This doctor was here to see me.

His office was thoughtfully dimmed. In the soft glow of the vision test projector, I could tell he was graying at the temples. He politely asked where I went to college. When I told him Columbia, he tsk’ed, “That’s not a very good school. Couldn’t you have gotten in somewhere better?”

My mother and I sat in stunned silence until he lifted up a newspaper clipping on his corkboard, revealing his class photo at Cornell. We laughed.

He did not call in any colleagues. He reviewed my records, apologized every time he shined that piercing penlight. The doctor showed me a diagram of my eye, sketched out a conical shape on a piece of legal pad paper. He shared his theory: my eyes were differentiated just enough from the median shape that contacts sat unevenly, roughly wearing at the edges of what unfortunately were the rims of my cornea. This rare phenomenon was called keratoconus.

“I can’t make any promises,” he said kindly. “Maybe in 10 years, if your condition stabilizes, we can get you Lasik to force-correct. But for now, your vision is still decaying. We have to fight it. I have some ideas ....” He inserted colorful rubber toothpicks into my tear ducts and prescribed several types of drops. “You will have to follow a regimented schedule. Can you do that?”

My mother held my hand in her lap. “Amanda is one of the hardest workers I know. She will do what she needs to do.” I felt her strength, copied and pasted it into myself.

“If this is the last year you can see, what do you want to do with that time?”

Back at Columbia, I carefully made a color-coded map of medications, taped it to the wall of my Hartley dormitory. I set dozens of corresponding, daily alarms. Afraid of failing my doctor, my mother and myself, I took my drops religiously.

For an Italian presentation, I made bruschetta; a roommate helped cut tomatoes so I didn’t slice my fingers off. While my suitemates went to parties, I laid in bed with a compress over my eyes, listening to movies I knew by heart. I took midterms in a private Disabilities cubicle with an extra hour and a computer, because I could type better than I could print. (As a child, I had memorized the QWERTY keyboard, plunking away on the family computer, “writing my stories.”)

I went home to Virginia. On that now-familiar train ride, I realized I could see, for the first time in months, individual birds in trees.

Walter Reed was empty on Thanksgiving; even the little coffee kiosk was closed. Our doctor sat alone in the waiting room, watching the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and cheerfully greeted us by name.

He did a vision test; better one, better two.

On his computer, he showed us imaging of my brown eyes, clicked a button that flushed them into aquatic blues and greens, revealing weaving lines that in another world could be rose vines. Scars, he said, all along your eyes, and they will be there forever.

Someday, he told me — softly, seriously — my vision could go again, glazed permanently. He was sorry for that, but was proud of the progress we had made together because, for now, with lenses, I could drive, read a blackboard, go to movies, see birds in trees. He was changing my legal vision status from blind to acceptable.

My mother cried, offered to come back with a pecan pie (hers is excellent), and he joked that would be a great trade for my vision and she threatened she really would and he blushed, said please seriously do not do that.

I returned for the spring semester with clear eyes and reflections about my remaining time at school and on Earth.

I passed all my classes. I made a video game for Contemporary Civilization that culminated in giving a friendship bracelet to Aristotle; my professor sat with me and played through it in one go. “I’m so proud of you,” she whispered. My Italian professor hugged me, encouraged me to stay in touch.

Under the pink blossoms of College Walk, I was aglow from my vision chrysalis.

I left my comfort zone and made an impromptu visit to Kent. For courage, I stopped at the Starr Library on the way up, stared past the long mahogany tables and ferns and books, and up at the stained glass depiction of Justice. Then, onward to the creative writing department. I was offered a cup of coffee by the encouraging department manager. I told her about my dreams but how intimidated I had been; did they offer summer courses? She smiled and waved her hand, as if worries were flies in the wind.

In May, I was accepted to two incredible summer internships: a film agency in Hollywood that would take me on one path, and a children’s literature office at a major publishing house in New York that offered another, alternate route. The latter meant I could take “Beginning Fiction” at Columbia and still qualify for the major. I had a choice.

I stayed in New York. Eight years later, that summer fiction professor wrote my recommendations for an M.F.A. in writing, where I am now. My loss of vision gave me the ability to see time, the most precious resource, and to see selfhood for what it was: the opportunity to choose, every day, who we want to be and what we can do to make that possible.

Amanda Tien ’14 is a writer, visual designer and marketing strategist. She is writing a novel and pursuing an M.F.A. in creative writing at the University of Pittsburgh. Previously, she worked for Camelback Ventures and Y&R Advertising, and was a 2015 Venture for America Fellow. View her work at amandatien.com.

By Munirat Suleiman ’24

Sweltering under the Georgia sun’s unwavering judgment, I quietly beg the universe for the day’s events to justify my lying to my parents.

I have never been to a protest in my life.

It’s a broiling June afternoon at the intersection of one of many churches, a local high school and the Snellville Towne Green, where the Black Lives Matter posters speckle the grass in front of me with stories of strife and disappointment. It’s a few months into the pandemic, and my summer is already careening toward rock bottom; I’d unceremoniously graduated from high school via PowerPoint slouched on my living room couch and watched murders of Black people on social media — formerly the only safe space I had left.

The air is restless with the buzzing of flies and conversations until an older Black woman steps to the far right of the field with a megaphone; she announces the protest’s route from the church’s field to the sidewalk by the highway, across the street and into the town green.

A mile or so, I estimate. I anxiously wiggle my toes in the sneakers I’d switched into from the heels my mother recommended with the dress I left the house wearing.

I told my parents I was attending a job fair.

Another organizer picks up where the last one left off, her voice like a deep spiritual asking the crowd to bow their heads and pray over the well-being of the Black community. She sings a hymn I don’t know and cites the Bible, something I’ve barely read.

There’s much I didn’t know before we got started, but there was something I did know: I was in my own personal hell.

I remember the first time I was condemned to hell. It’s an October morning, after Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and I am on a school bus heading toward yet another day of trivial third-grade matters. The weather can’t make up its mind about whether it wants to reminiscence about the summer or press into winter, and thus it’s a still and neutral day.

I spend my time daydreaming about Emily the Emerald Fairy, a Rainbow Magic book about an emerald gem fairy who matches the color of my family’s most valued Quran over the fireplace. Despite this simple escapism, reality seeps in from the conversation between the two white girls in front of me discussing their long weekend.

Their voices project above everything else as paper airplanes clumsily traverse the ends of the bus and the fifth-graders boss the younger kids to make space for their friends to sit together, much to the driver’s chagrin.

None of their words make their way into my consciousness like the following confident statement by the taller of the two: “Well, of course! Everybody’s Christian!”

Unaware of the context, but knowing this to be false, I innocently correct her by proudly interjecting, “I’m not! I’m a Muslim!”

I wish I hadn’t. I already feel different enough being one of the few Black children on the bus, never mind in the entire town. It’s why I resort to my books when my peers throw a quick “Blacks” or other racial slur into the air for cheap thrills.

No one would interact with me either way, and I suppose my interjecting was a self-affirmation that I existed in the real world.

Regardless, I desperately wish that I could claw the words from the atmosphere as she turns, her face wrinkling from surprise to disgust, and snaps: “You can’t say that you’re not Christian. If you’re not, you’re going to hell.”

I’ve come to understand that hell is a place for sinners and “others” that society chooses, like Dante’s totally unbiased allocation of different figures to the circles of hell. (I don’t forget the Prophet Muhammad being in one of the worst ones.) A condemnation was just a confirmation of my hyperawareness of my differences — both the obvious and the obscure ways that I have to carry more identities my whole life long, whether it be because I’m a first-generation American, Black or Muslim.

Something I’ve asked myself more and more is, “How much different is hell from the world I already live in as a Black woman, where my sin is being inconvenient for society?”

Religion was hard to wrap my head around as a Muslim child and even now as an agnostic adult; but though I was young, I had more than enough knowledge to understand what that girl on the bus meant about me going to hell. Growing up from that moment, I only had two missions: to be invisible and to be successful; one for myself, one for my family, both for survival.

My childhood turned unhealthy with me hiding myself in the fear that everyone else would see that I was going to hell, that my differences were screamingly shameful.

I only had two missions: to be invisible and to be successful; one for myself, one for my family, both for survival.

I never forgot to wrap my hijab around my face during car rides to the masjid, to remove any native Nigerian clothing before entering school events (and have excuses ready as to why), to breathe whenever a “friend” said something racially insensitive. I never forgot to keep track of where I said I was born, to write the list of names I’d choose for myself when I turned 18, to evade talking about my personal struggles with my parents or my friends, to predict anything and everything that could ruin my self-made facade and avoid it without exposing myself.

These were the different circles for my personal hell, one I gradually built from the hellfire society gave me.

God only knows how I never forgot.

The older I became, the more my goals opposed each other as I stopped believing in respectability. Sure, I was academically successful, devoid of a personality as I intended — but I was miserable above all else, and exhausted with the facades I’d worn since childhood. It was ironic that I wanted to be invisible, yet who I was would never permit me that privilege, no matter how hard I tried.

I let go of certain mental weights during high school. And as I would later come to terms with, I would have to be visible if I wanted to change my sentencing in life.

Like our convictions, it feels like the sun is growing tenfold, and I can’t help but wonder if this is what it is to actually live within yourself. The black top I’m wearing doesn’t help matters; the BLM protest organizers advised us to wear loose black clothing to make our bodies harder to identify, if necessary.

I try to compose myself as the group climbs up a hill and then onto the sidewalk by the highway to cross the streets to the green. The highway is eerily empty, but there are some honks of support every few minutes.

Strangely, the weather takes on a stillness similar to the one I’d experienced a decade prior, with the sky darkening like the face that looked me in the eyes that fall.

Rain clouds crowd around, taunting us to retreat, when a volunteer screams, “There was always a chance of rain, but our voices, our identities, our lives will be seen rain or shine.”

Most everyone had umbrellas at the ready. I forgot to check the weather forecast. I begin to mentally rehearse excuses for my parents. We fill the town green, chanting “Say her name!”

“Breonna Taylor!” “What’s his name?” “George Floyd!” and forging a circle before kneeling for eight minutes of silence. In this silence, the sky can’t hold on to the pain any longer; it rains like the collective tears on the faces of Black Americans forced to rewatch crimes against their humanity. The details make me dizzy as we rise up and congregate for speeches.

I remain in the moment before hearing a jeer: “Go home or go to hell!”

The headache from a decade ago returns from beyond the grave of my childhood innocence, but this time I face a choice.

I like to think that the girl from third grade didn’t understand what she was saying. That she was merely repeating something she had learned from church or her parents, sentiments that developed after 9-11, right before we were born. She had innocence if not ignorance, and probably still does.

But what happened to my innocence? The innocence that society is desperate to rip from Black children before they’re even preteens, the innocence taken the minute someone realizes that the world is not built for them to succeed, the innocence taken from me?

Could I have lived a more honest and free childhood?

Over the next few hours, powerful memories and speeches are shared, and the City Council issues a proclamation of racial equality.

I ask myself: “Where do we go from here?”

“Before I Let Go” blasts from speakers as people dance at the protest’s end and the sky reopens to us. There’s a rainbow over our fists, stretching from the green, over the church and the high school.

I drive with a high school friend to a grocery store and wander the aisles before talking over ice cream from our separate cars, for social distancing’s sake.

I wish that life had a similar narratively beautiful reconciliation, a nice rainbow at the end. With the sunset beginning, I pause and consider putting the outfit I’d worn leaving the house back on, going home without a trace as to where I’d been, or driving aimlessly around the parking lot to burn time.

I decide, however, to leave those clothes on the passenger seat and take the highway straight home.

Munirat Suleiman ’24 (she/her) hopes to study English or sociology with a concentration in human rights. Hailing from a small town an hour from Atlanta, she loves nurturing intimate communities through service and storytelling. If she isn’t writing, she can be found daydreaming to her favorite songs or sharing personal philosophies in parking lots.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu