|

|

|

|

|

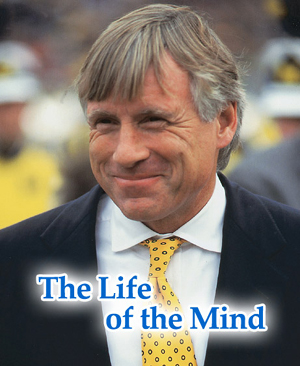

The Life of the Mind by Alex Sachare '71 Lee C. Bollinger assumed office as Columbia’s 19th president on June 1. He did not, however, move into the stately president’s office, Suite 202 of Low Library, on that date. That part of the building, like so much of the Columbia campus, was undergoing renovations during the summer, so for his first few months, Bollinger conducted business in a fourth-floor Low aerie that previously had housed the coordinator of the presidential search committee that selected him. What makes a university president? More specifically, what qualifies a person to assume the helm of Columbia University, one of the world’s most prestigious institutions of higher learning? Clearly, Bollinger has the résumé for the job. Since November 1996, he had been president of the University of Michigan, an institution with 19 schools, 53,000 students and a $3.5 billion annual budget, so he has experience running a major university. He has Ivy League administrative experience as well, having served as provost of Dartmouth College. His academic credentials include 21 years on the faculty at Michigan Law School, including seven years as dean. And he has several Columbia connections - he graduated from the Law School (where he was articles editor of the Law Review) in 1971; his wife, Jean Magnano Bollinger, an artist, has a 1971 master's degree from Teachers College; and his daughter, Carey, graduated from the Law School last spring. He also has a son, Lee, a graduate of UC Berkeley and Michigan Law School. But it takes more than a résumé. Henry King '48, chair of the search committee (as well as the committee that found Bollinger's predecessor, George Rupp), has described Columbia's new president as "a dynamic leader and an academic visionary" who has "not only scholarship, but a track record," and praises his "commitment to the highest education standards and his responsiveness to student issues and concerns." Rupp has called Bollinger "a tremendously impressive academic leader," while James O. Freedman, president of Dartmouth when Bollinger was that school's provost, remembers that he "had unerring judgment." Jack Dixon, co-director of the Life Sciences Institute at Michigan, one of Bollinger's top projects, recalls how everyone "was impressed by his presence, his depth of understanding and his ability to ask key questions." Born in Santa Rosa, Calif., and raised there and in Baker, Ore., where his father owned a newspaper, Bollinger, 56, is a graduate of the University of Oregon. He served as law clerk for Judge Wilfred Feinberg '40 on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and for Chief Justice Warren Burger on the United States Supreme Court before launching his career in academia. His teaching and scholarly interests are focused on free speech and first amendment issues, and he has published numerous books, articles and essays in scholarly journals on these and other subjects. His books include Eternally Vigilant: Free Speech in the Modern Era, co-edited with Geoffrey R. Stone (University of Chicago Press, 2001), Images of a Free Press (University of Chicago Press, 1991) and The Tolerant Society: Freedom of Speech and Extremist Speech in America (Oxford University Press, 1986). He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, an honorary fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge University, and a member of the Boards of the Gerald R. Ford Foundation, the Kresge Foundation and the Royal Shakespeare Company of Great Britain. He is the recipient of several awards for his strong defense of affirmative action in higher education, including the National Humanitarian Award from the National Conference on Community and Justice. An avid runner who has been spotted on the trails of Riverside Park, Bollinger was acclaimed for his accessibility at Michigan, where he frequently conducted "fireside chats" with students and hosted an open house to celebrate Michigan's football team's appearance in the 1998 Rose Bowl. When Rupp announced in March 2001 that he planned to retire at the end of the 2001-02 academic year, Bollinger's name immediately arose in speculation about Columbia's next president. That speculation became reality when the search committee quickly recommended Bollinger's selection, and he was elected by the Board of Trustees on October 6. Since then, he has spent much of his time in New York, reacquainting himself with the Columbia community so he could hit the ground running on June 1. During his first week on the job, Bollinger graciously agreed to an interview with Columbia College Today. Following are excerpts: In broad strokes, how do you view the role of University President? What is your personal mission statement for the job?

First and foremost, you have to be determined to preserve and enhance the intellectual, academic excellence of the institution. That's what we are about. The president has to make that the principal object of his attention. That means everything from making sure that the youngest people in the institution, people coming in as first-year undergraduates, have a life-changing educational experience, all the way to being the most creative in fields that we deal with as a university. Preserving the atmosphere in which this all occurs is extremely important. I think it's a fragile atmosphere. The intellectual environment in which we work is not the same as other sectors of society. That's not to say it's better than the intellectual atmosphere in other sectors, but it is different - and it is crucial for society that we have these centers of intellectual activity. A second role of a university president is to engage the outside world in that activity. In a sense, you stand as a kind of intermediary between the university world and the outside world. You both help interpret and explain what it is that we do to the outside world, and you help bring messages from outside into our community. Many people do that; I'm not saying that the president is the only one, but it is a key role of the president. It is the source of development work, it is the source of government relations, it is the source of, the nature of, alumni/alumnae relations. That's a crucial role. Third, tens of thousands of details all add up to making an institution work: the financial side, the service side, the physical facilities, the landscaping, the quality of architecture, making sure that the food is good and delivered in an appealing way. The range of these concerns really is quite incredible. The last thing I'd say is that you try to peer into the future and make some guesses, hopefully informed, based on good judgment, as to how the institution might evolve toward that future. That is a very exciting part of being a university president. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||