Writer Kevin Fedarko ’88 took the hike of a lifetime

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Writer Kevin Fedarko ’88 took the hike of a lifetime

Kevin Fedarko ’88

©KDI PHOTOGRAPHY

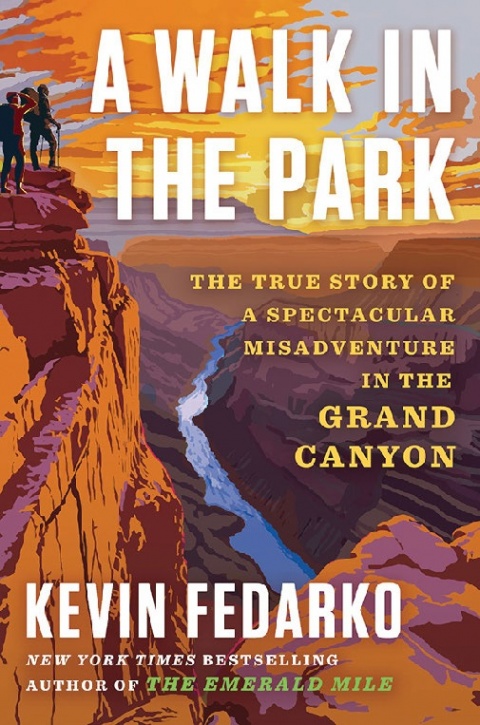

The pair averaged 15 miles a day, often in 100-plus-degree heat. To get a sense of how mind boggling and dangerous their bushwacking was, consider this: Fewer people have done what Fedarko and McBride did than have walked on the moon. “This landscape would pare you down, too, peeling away the layers until it had stripped you into something that, not unlike the land itself, lay very close to the bone,” Fedarko writes in his new book, A Walk in the Park: The True Story of a Spectacular Misadventure in the Grand Canyon (Scribner, $32.50).

Fedarko went into the canyon — “a holy place; a cathedral in the desert,” he writes — for very personal reasons. He was 50 when his expedition began, and hoped he might return “with a better grasp of who I was, and perhaps a renewed sense of whom I might become, before it was too late to grow and change.”

The grandson of a Pennsylvania coal miner, Fedarko grew up taking Sunday hikes with him through mounds of oily black slag and crushed shale along the Youghiogheny River. After graduating from the College, eager to escape Manhattan’s steel canyons, Fedarko headed west and became a guide for a whitewater outfitter on the Colorado River. He later turned his experience rowing sharp-bowed, hard-hulled dories into his first book, The Emerald Mile: The Epic Story of the Fastest Ride in History Through the Heart of the Grand Canyon; it won a National Outdoor Book Award in 2013.

Yet he says his mastery of the canyon’s watery world made him overconfident. “To have mastered the nuances of whitewater is inadequate preparation,” Fedarko says. “For the moment you step away from that world, you enter the world of rock, where a very different set of rules apply, and you never master any of it. It ultimately masters you, and you surrender to that larger truth and then draw what conclusions and insights and gifts follow from that.”

The world of rock was a world of suffering. “The bottoms of my feet looked like someone had fired a shotgun into them,” Fedarko notes after the first blazing-hot leg of his trek. “It [was] like the sun [was] tapping on the top of my head with a ball-peen hammer.”

But A Walk in the Park is more than an adventure saga or a recounting of each day’s blisters, burns and burdens. Fedarko learned about Native American rights, overtourism and pollution. He also became more humble and grateful. “Powerful landscapes strengthen the connective tissue, the bonds that bind people together,” he says.

Writing the book was also a struggle — one that took seven years. “When I was in the canyon, I didn’t think that there could be anything less pleasant and more awful than walking from one end of Grand Canyon to the other,” he says. “Then, of course, I discovered that indeed there is, because writing about walking through the canyon is far worse.”

The first deadline wrecker came when Fedarko realized he wanted to chronicle the canyon’s 1.7-billion-year geologic history, and report on its 9,000-year history of human habitation. He gave particular attention to the plights of the Hualapai and Havasupai, the Native American tribes that call the Grand Canyon home. “Writing the book was like going to graduate school for geology, botany, hydrology and human history,” he says.

Getting the words onto the page posed a second problem, even though Fedarko has the gift of speaking in complete sentences that are both lush and grammatically correct. He calls his work process, perhaps too harshly, “a complete mess” and likens it to his canyon trek.

“When you’re making your way on foot from the eastern end to the western end of the Grand Canyon, that journey is defined by the fact that there is no trail. You’re continuously moving into and then back out of tributary canyons — endless, endless detours.

“And that’s exactly what writing this was like,” he says.

In A Walk in the Park’s first chapter, excerpted here, Fedarko attempts to frame the scale and vastness of the canyon, setting the stage for his pilgrimage through a landscape that is broadly recognized by many, but experienced by very few.

Ultimately, Fedarko realized neither words nor pictures could capture the canyon’s essence and impact. Silence, he concluded, was its “least appreciated treasure,” one that might have the most powerful impact on the soul.

“Dense, crystalline silence blankets the landscape,” he says. “The stillness that accompanies that silence opens a space inside you for things we don’t get to do in the world beyond the walls of the canyon — contemplation, introspection, reflection.”

— George Spencer

Strictly speaking, the topography of the canyon — which can perhaps best be imagined as a range of mountains roughly the length of the Pyrenees flipped upside down and countersunk below the horizon — has a total surface area no bigger than that of Delaware. But even so, those whitewater guides deserve some credit for putting their fingers on an important truth, because few things come closer to capturing the canyon’s stupefying depth and labyrinthine complexity than the possibility that it might somehow be capable of swallowing up the entirety of the Lone Star State.

If there’s a key to framing the scale and vastness of that abyss, it lies within the tiered walls that descend from the canyon’s rims — one set running along the north side, the other along the south — whose longest drop exceeds six thousand vertical feet: tall enough that if five Empire State Buildings were stacked one on top of another, they would barely reach the highest point on the North Rim. In fact, the total loss of elevation from rim to river is so great that the climate actually shifts, becoming significantly hotter as one descends. With every thousand feet of drop, the temperature increases by roughly 5°F, giving rise to a ladder of meteorological zones and niches so discrete that the flora and fauna at the top bear little if any relation to the forms of life on the bottom.

Inside the canyon below, life-forms from three of North America’s four deserts — the Great Basin, the Sonoran, and the Mojave — all collide and commingle. Here the air temperature during the summer will push beyond 120°F, while the surface temperature of the stone can easily claw its way up to 170°F — hot enough to kill a snake caught in the open within a few minutes, or cook a Giant Hairy Scorpion in just less than an hour.

Under these conditions, only the hardiest things can persevere: tiny tree frogs that bide their time in rocky crevices for months on end; spiders capable of waiting two hundred days in a burrow without a drop of water; seeds with the patience to remain dormant for an entire century until, under just the right circumstances, they give themselves permission to sprout. There are species of cactus whose limbs retreat into the ground, and in some areas even the streams are rendered so tenuous by the heat that their waters recede into the stone by day and emerge only by night, trickling timorously beneath the bleached gaze of the moon and the stars.

Nowhere else is the ground so broken and the past so exposed. Nowhere else can a person move simultaneously along so many different dimensions: forward in space, backward in time, and across the face of an entire hemisphere of life zones, ecosystems, and biological communities. Nowhere else is the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other so provocative, so destabilizing, so densely freighted with rich and interlocking layers of meaning.

And perhaps most extraordinary of all, the contours of no other landscape are so broadly recognized by so many even as its essence remains known — truly known — to so few, because glimpsing its deepest secrets and ferreting out its hidden treasures requires something that only a small number of us are willing to embrace. An undertaking that extends well beyond what Theodore Roosevelt called for when he referred to the canyon, in a speech he delivered on the South Rim in the spring of 1903, as “one of the great sights which every American, if he can travel at all, should see.”

Aside from simply looking at it, you must lace up your boots and actually step inside the place.

When Pete first approached me with his proposal for a walk in the park, I didn’t need much of an introduction. For most of my life I had been obsessed with the canyon and had even spent a number of summers living and working on the Colorado as an apprentice whitewater guide, a story we’ll get to in good time. This may not have qualified me as an expert. But I viewed myself as someone with enough knowledge and experience to feel that he knew what he was getting into by agreeing to tackle the place the hard way: moving through it on foot.

Alas, although I didn’t know it at the time, I didn’t have the faintest clue how truly unfit Pete and I both were, in every possible way, for a journey that would pull us into parts of the canyon where, for good reasons, few travelers have ever been. A journey that was supposed to last no more than a couple of months, but would ultimately turn into the longest, most arduous ordeal that either of us had ever endured while forcing us to confront at multiple points along its arc the question of why we had bothered to start, and whether it was worth the trouble of finishing. But it was also a journey in which the canyon would show us things we had never dreamed of.

At the start of this quest, I had no way of imagining that long after it was over I would still be struggling to formulate a coherent response to the miseries the canyon inflicted on us, the satisfactions that would later overtake the memories of that misery, or the yearning and splendor that transcended them all. I had no way to fathom the force with which the canyon’s austerity, its grandeur, and its radiance — traits that stand implacably aloof to human hopes and ambitions — can impart a perspective that will enable you to see yourself as nothing more, and nothing less, than a grain of sand amid the immensity of rock and time and the stars at night.

Excerpted from A Walk in the Park: The True Story of a Spectacular Misadventure in the Grand Canyon by Kevin Fedarko. Copyright © 2024 by Kevin Fedarko. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu