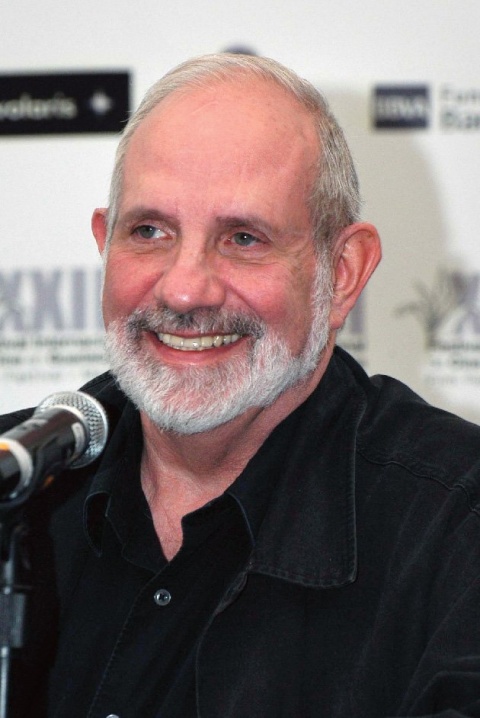

Master of suspense Brian De Palma ’62 is back with an entirely new project.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Master of suspense Brian De Palma ’62 is back with an entirely new project.

Wikimedia / Festival Internacional de Cine en Guadalajara

Celebrated movie director Brian De Palma ’62 has always been known — like his idol Alfred Hitchcock — as a master of the unexpected. Again and again, in movies from Scarface to Mission: Impossible, a scene will grab us in suspense, as tightly as the bloody hand reaching up from the grave in Carrie’s final moments. So it shouldn’t be any surprise that, at almost 80, De Palma has one more plot twist in store for us: his first published novel.

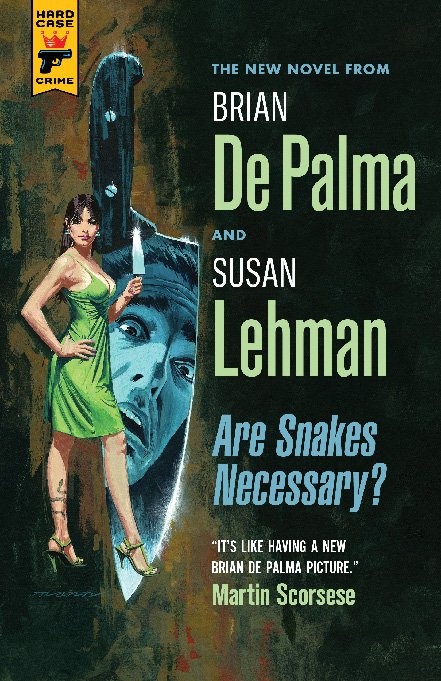

Are Snakes Necessary? (Hard Case Crime, $22.99) — co-written with his partner, Susan Lehman, a former New York Times editor — is set in the murky moral terrain familiar to his film’s fans. It’s a pulp noir political thriller, a genre that De Palma clearly loves. He tells CCT that both “the brutal directness of the prose” and “the characters — sexy, duplicitous women, morally flawed men” — appeal to him. Along with the auteur’s trademark gotchas, De Palma and Lehman provide references to Hitchcock and others in the cinematic pantheon. (Its quirky title is a film-nerd in-joke, name-checking a book glimpsed in Henry Fonda’s hands in Preston Sturges’s classic screwball comedy, The Lady Eve.)

De Palma’s gritty thriller was a perfect fit for its noir publishing imprint, co-founded in 2004 by Charles Ardai ’91. Ardai was excited to publish the director’s work, and was impressed by De Palma’s “sharp, ruthless look” at current politics. “This is not just a great crime story,” he says. An added bonus was Ardai’s “delighted” discovery that De Palma was also a College grad. “When I was a student, I had the opportunity to meet, and in some cases study under, some truly towering figures — Grace Paley, Philip Roth, Allen Ginsberg ’48, Mary Gordon. In some ways I like to think of getting to work with Brian now as an extension of that exceptional Columbia experience.”

De Palma with his co-author, Susan Lehman.

courtesy hard case crime

It was in fact at the College that De Palma, a surgeon’s son from Pennsylvania, discovered his lifelong métier. When he arrived in the late ’50s, the teenage science fair whiz was studying to become an engineer. But the radical winds blowing through Morningside Heights in those years had a bracing effect. French New Wave cinema was all the rage, and De Palma became entranced by Jean-Luc Godard, the Maysles Brothers and the classics of John Ford and Howard Hawks. “He hocked all his scientific equipment for a Bolex movie camera,” People magazine once noted.

Although much of his filmmaking education took place off-campus, De Palma was able to learn key storytelling basics from professors such as Robert Brustein GSAS’57 (later head of Yale Drama School). De Palma remembers reading Ibsen’s plays in Brustein’s class; he says he still thinks of lines like those from the emotional finale of The Master Builder. “It was my initial introduction to masterful dramatic writing,” he says. “Lessons learned in that class live in my writing today.”

As his cinematic skills developed, De Palma progressed from making avant-garde short films (like Woton’s Wake, with William Finley Jr. ’63) to counterculture satires (Greetings; Hi, Mom!) and documentaries for hire. “I was a very good cameraman,” he remarks with superb understatement in a 2015 documentary, De Palma. He ended up at Warner Bros. in Hollywood, where he became part of a cohort of up-and-coming early ’70s filmmakers, alongside Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. The young directors helped each other succeed, passing scripts back and forth and working together on casting. According to Scorsese, De Palma “took him under his wing” when he went to Los Angeles, introduced him to Robert De Niro and even gave him the script for Taxi Driver. “He is a warm, passionate, compassionate person who, I think, puts on a tough front,” Scorsese told People.

What set De Palma apart was his focus on horror and his “operatic and balletic” camerawork — “simultaneously voluptuous and incisive,” as critic Michael Sragow wrote in Film Comment in 2016. The name “De Palma” on a film conveyed a sense of menace to viewers, but it also signaled the presence of an artist’s vision. As De Palma’s directing choices evolved, cannily alternating between large-scale studio assignments (The Fury, The Bonfire of the Vanities) and more indie “passion projects” (Home Movies, Raising Cain), the indelible films that movie buffs know — among them The Untouchables, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out and Carlito’s Way — got made. De Palma, as one cinematographer has said, is simply “one of the greatest visual filmmakers around.”

With its visual scene setting and crime-ridden twists and turns, the novel benefits from De Palma’s cinematic sensibility. Writers like Bret Easton Ellis admire its pacing and style (“a fast-moving page-turner”). But let’s leave the last word to De Palma’s old friend Scorsese. Of this novel, he says, “You have the same individual voice, the same dark humor and bitter satire, the same overwhelming emotional force. It’s like having a new Brian De Palma picture.”

Aging is not an entirely pleasant affair. One day Connie was the beautiful Bryn Mawr graduate. The whole world was open in new ways. Doctor, lawyer, Indian chief. Connie had choices her mother never did. Bryn Mawr pushed hard for certain career choices. Connie’s roommates were both going to medical school.

But medicine was not a viable option: Connie didn’t give a hoot about radiology or endoskeletal whatevers. Numbers weren’t Connie’s strength, so banking made no sense. Anyway, her father had money, so work wasn’t an issue.

Frankly all Connie really wanted was to get married. She could raise children — and maybe horses — and read great books and have a garden and make wonderful meals and plan nice vacations.

And oh, she’d love her husband, ambitious, fierce-minded, fair, strong, successful. She’d care for a fabulous house, assemble it in good taste, and have nice parties and interesting friends (from good families). Connie couldn’t tell anyone any of this. It would be too embarrassing.

That pretty much left law school as the sole viable option.

Columbia was a bit of a shock when she first arrived. But Connie stuck to her dorm, outlined her cases and generally applied herself. She met Lee in her second year and paid far less attention to torts and contracts after she did.

“Bring your lunch and meet me by the river. The 114th Street entrance. At Riverside Drive. You’ll recognize me. I’ll be looking for you.” That’s what the note in Connie’s book bag said. She found it there one morning after criminal law class ended. Connie remembers the note vividly, each syllable.

Rogers produced a blue-and-white bag with the Columbia mascot (a lion) on it. “Roar,” he said, pulling out a bottle of sparkling pink champagne. “Matches the sunset. And your smile.”

Professor Simon had called on the handsome dark-haired man next to her. “Mr. Rogers, can you tell us please, what is the issue in Brady v. Maryland?” Mr. Rogers had exactly no idea. “Professor Simon,” he said, “I have exactly no idea what the issue is in Brady v. Maryland.”

No one had had the guts to say anything like that before. The class cheered. Lee Rogers came as close as a person could come to taking a bow without actually moving.

Unimpressed, Professor Simon called on Connie Salzman, who quite matter-of-factly delivered the perfect analysis of the Brady rule of exculpatory evidence case. Of course she knew the issue. She’d spent the weekend in her room studying, going through the cases over and over until they practically extruded through her skin.

Connie brought her lunch (a frisée salad) to the river with some trepidation. Who was this smooth-talking Lee Rogers and why did he want to have lunch with her?

Rogers, who’d brought a hot dog for his lunch, spread mustard over the bun with his finger. He produced a blue-and-white bag with the Columbia mascot (a lion) on it.

“Roar,” he said, pulling out a bottle of sparkling pink champagne. “Matches the sunset. And your smile.”

He pulled two plastic champagne cups from the bag and started to pour.

“First things first,” he said, and took a bite of his frank. “Yum.”

Connie smiled. She was charmed.

But she couldn’t help herself. “Do you know what’s in those?”

“Whatever it is, it sure tastes good.” Lee smiled.

“Have you ever visited a hot dog factory?”

Rogers’ eyes twinkled. “Was that on the college tour? I didn’t pay much attention after Butler Library.”

Connie loved it that he was playful. She giggled — something about him brought out the coquette in her.

“They mix pork trimmings with pink slurry. That’s what you get when you squeeze chicken carcasses through metal graders and blast them with water.”

Admittedly, Connie’s idea of coquettishness was a little odd. She hadn’t had much practice. But Rogers was not put off. “How about the bun?” he said.

Connie liked the way he teased. “This is before the bun! Listen. They mix the mush with powdered gunk — preservatives, flavorings, red coloring all drenched in water and then squeeze it through the pink plastic tubes where they cook and package them.”

“Now the bun?”

For the life of her, Connie couldn’t figure out why she was talking about hot dogs. Something about Rogers made her nervous. The talk was like a tic. But he was having fun. And she couldn’t help but enjoy herself.

“Right. Now the bun. I don’t think you’re taking this very seriously.”

“I’m very serious about my hot dogs. Also I’m serious about you, Miss Brady v. Maryland. You look very delicious yourself.”

He said this straight out of the blue. Connie blushed.

“Hey! There’s some pink slurry flushing across your face.”

Connie blushed more. And giggled. What was it about this guy?

Rogers lifted his glass. “To exculpatory evidence.” They took a quick sip from their cups. Rogers moved closer. He smelled Connie’s sweet (expensive) perfume. “Mmmm. Delicious, yes! And no plastic packaging?”

Connie loved this. So much so, that to her enormous surprise, she heard herself say, “Only one way to find out.”

“And what would that be?”

Connie lightly brushed her lips against his. “Any sign of plastic packaging?” she said.

“Nope!” said Rogers. He kissed her again shyly. “What do you think? Will I survive that hot dog and all those toxins?”

“I hope so,” said Connie and she did. “Take my breath away,” she added. And he did.

A courtship began. Connie helped Rogers outline his cases and prepare for exams. He took her to jazz concerts at divey bars downtown. She got all As. He got offers from the top firms.

Rogers clinched matters when he took Connie to Paris right after graduation (she graduated third in her class; he didn’t rank) and proposed to her.

He did not want to be without this fine-looking, straight-thinking woman. He needed her. He loved her too. There was no question: Connie would be the perfect wife.

Connie was over the moon.

You probably want to know what the sex was like then. I’m sorry, Connie Salzman was not the type of girl who talked about things like that. She liked Lee Rogers. A lot. Let’s leave it at that. He made her laugh. She did things with him she couldn’t imagine.

They were married six months later. Lee had a job at a big Philadelphia firm. Connie had a job at a bigger Philadelphia firm. The job was not interesting. Even slightly.

Connie did not have to worry much about any of this for long. Two months after she started work, she discovered to her delight — true, actual and complete delight — that she was pregnant. The trouble with Lee might have started around this time.

Connie was dizzy with happiness about the pregnancy and might have lost track. Dinner might have slipped; Connie absolutely did not plan the spring trip to the Alps that year. That she remembers. Lee went instead with a bachelor friend from his firm.

Connie would never have found out about the stewardess he met on the flight. She wasn’t a suspicious spouse or anything like that. But she phoned Lee in the Alps — the connection was bad and she thought she’d misheard the hotel operator; she asked for Mr. Rogers and the operator said, in thickly accented English, “I em so sorry, Ma’am. Meester and Meesus Rogers just check out now.”

Connie actually said, “No. Not Mr. and Mrs. Rogers. I’m looking for Mr. Rogers. I am Mrs. Rogers!”

“I em so very sorry,” said the voice on the phone. “So very sorry.”

Connie was actually confused and wondering why on earth the operator was so very sorry when the awful truth dawned on her.

Lee’s homecoming was not so pleasant as previous ones. Connie did not pick him up at the airport, but was instead waiting for him when he got home.

“Lee. We have to talk,” she said.

Rogers had never seen such a stern look on Connie’s face. Pregnancy, he thought, makes animals of all of us.

“Who were you with in the Alps? I know you weren’t alone. I know you were with a woman. Lee. What. Are. You. Doing?”

Lee Rogers was on his knees so quickly Connie thought he’d had a heart attack. It took him just a few tearful moments to tell her, choking back tears, that yes, he was with a stewardess, someone he’d met on the plane.

He was scared of being a father, he said. Just scared in a way he’d never been before. “I lost my mind, Connie. I was so afraid. I wanted to be a man for you, a strong man who wasn’t afraid, and I wanted to be a strong father for our baby, and Connie, Connie, Connie,” he choked back more tears, “can you forgive me? Ever? Oh god, Connie! Please help me to be worthy of you — your love, our baby.”

This could’ve been the end of all that Connie had ever dreamt. She wasn’t going to let it slip quickly out of hand.

Determined to save herself, her baby, and the family she dreamt of, Connie got in the car and drove to Bucks County, to the small country house her father had given her and Lee for a wedding present.

Connie had planted a little garden there and it was there that she would find the peace she needed to survive this glitch on the long road she knew would lead to a happy ending for her, for Lee, and for their unborn child.

It was high spring. Connie knew just what she’d do. She’d plant a cherry tree like the ones that had just blossomed in the capital. Sweet, pink and fragrant, the trees represented all of nature’s promise.

Trees with sour fruit last longer — up to two hundred years. As a statement about her conviction and the promise of this pregnancy, Connie chose one of these.

She loaded the sapling into her car, ferried it to Bucks County and planted it before she even went inside the house.

Twenty years later, worried about herself and her odd behavior, Connie drives the familiar road to Hillside Lane. There, in front of the house, the first thing she sees is the cherry tree she planted all those years ago.

Now fully mature, it blossoms magnificently over the drive. For Connie the tree is a horrible sight. Each bright pink bloom is a reminder of that time, of what happened with the stewardess.

What happened happened — a long time ago. And then it was over. Lee said it was.

And it was.

And it was awful and unspeakable to have accused him again, to have impugned his integrity with her crass inquiry about the video girl.

It was weak to have questioned him. Rogers made a promise all those years ago: if Connie could forgive him — and she could, she did — never again would he violate their vows or give her cause to worry, ever. A simple exchange: absolution for fidelity, forever.

And she had sunk to questioning his veracity, his honesty. She had violated their trust.

She goes to the shed. On a neat pegboard hang all the tools you’d need to build a new world — hammers, drills, saws. Connie surveys the tools and, at last, sees the hatchet she is looking for.

She picks it up. Weaving just a little, she carries the hatchet to the front of the house and plants her size 5 feet onto the earth and then she takes a wild swing — not one, in fact, but six — and she does not stop then but continues to hack, chop chop chop, at the twenty-year-old tree that bears with its fruit the bitter memory of Lee’s twenty-year-old sin.

The tree falls. The crash is loud. Connie is satisfied. Gone is the tree that memorializes Lee’s one and only transgression. She will not question him again.

From the book Are Snakes Necessary? by Brian De Palma and Susan Lehman. Copyright © 2016, 2020 by DeBart Productions, Inc.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu