Michael Waldman ’82, an authority on the right to vote and the American presidency, sees our democracy at an inflection point.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Michael Waldman ’82, an authority on the right to vote and the American presidency, sees our democracy at an inflection point.

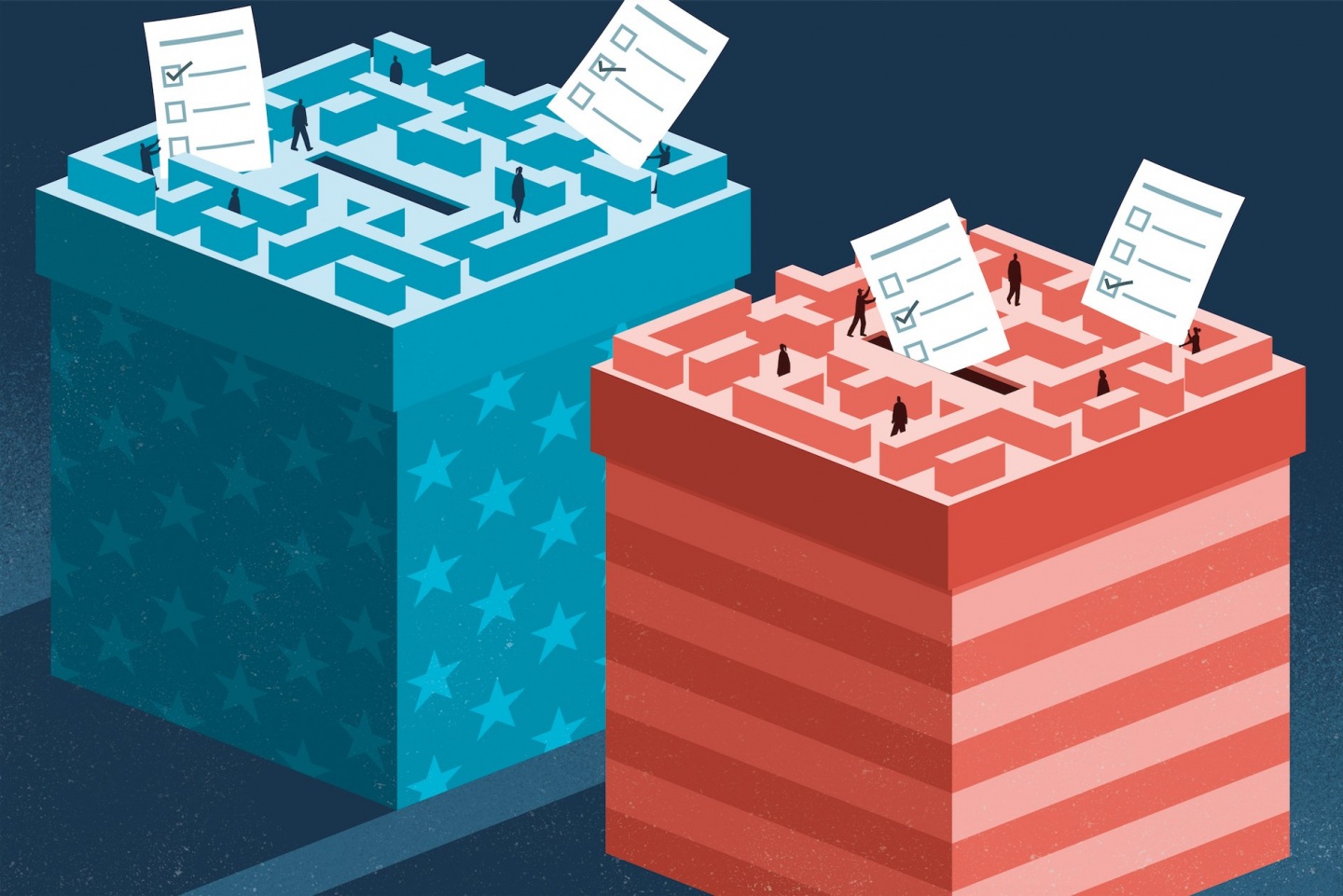

Illustration by Davide Bonazzi

By Jamie Katz ’72, BUS’80

The right to vote is the bedrock of democracy. Yet throughout the nation’s history, the tension between those who would uphold and expand that right and those who would restrict it has engendered battles that rage to the present day.

Even before this year’s coronavirus pandemic, economic crisis and newly urgent demands for racial justice, there were serious concerns about such issues as voter suppression, foreign interference and election security in an atmosphere of poisoned political discourse. And now, with the 2020 presidential showdown looming and stakes as high as any since the Civil War, anxieties about the election are only intensifying.

Michael Waldman ’82

Courtesy of Brennan Center for Justice

Originally from Great Neck, N.Y., Waldman majored in political science at the College and edited Broadway, a magazine supplement to Spectator. He also jumped into the punk rock scene downtown, and fondly remembers the night the Ramones played at Ferris Booth Hall, throwing guitar picks to the audience. “New York in the late 1970s and early ’80s was a pretty gritty place,” Waldman says, “but people who went to Columbia took pride that they weren’t in the cushiest of schools.”

Waldman now lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Elizabeth Fine, the general counsel for New York State Empire State Development Corp.; they have three children.

Following are edited excerpts of the conversation.

Columbia College Today: Before we dive into specific concerns about the 2020 election, can you point to some of the key mileposts in the evolution of voting rights in America?

Michael Waldman ’82: From the beginning of the country we’ve fought over who would have a seat at the table. It has always been a raw fight over power and over American ideals and identity.

When the nation started, we were anything but what we would regard today as a meaningful democracy. Only white men who owned property could vote. That was inherited from Britain. But the ideals of the American Revolution created new expectations. When Jefferson wrote the preamble to the Declaration of Independence, it didn’t just break with Britain; it said that government is legitimate only if it rests on the “consent of the governed” — a radical idea then and now. And he wrote it while being attended to by an enslaved 14-year-old boy, so he was a hypocrite. But his ideas were so powerful that immediately, pressure arose to expand American democracy.

On the issue of voting, however, the founders were divided. The constitution of the new state of Pennsylvania, written by Benjamin Franklin, eliminated the property requirement; meanwhile, in Massachusetts, John Adams was aghast at this liberal notion. He warned that women, lads of 18 and men who have not a farthing to their name will also demand a right to vote. “There will be no end of it,” he said. And that’s really the story of the country: It’s this push for greater participation, and resistance from people who have power already, trying to push back.

CCT: Franklin’s more expansive view gradually took hold.

Waldman: Yes. Ironically, given our current political moment, the first great voting rights expansion and victory in America was won by angry, white, working-class men. They were supporters of Andrew Jackson and the Democrats in the 1820s and 1830s. And they got rid of the property requirement so that working-class people and poor people could vote.

Then you had the Civil War, which led to Black men winning the right to vote. Lincoln was not a supporter of Black suffrage before the war, but the war changed him, as it did so many other people. You had hundreds of thousands of Black soldiers, former slaves and others, fighting in the Union Army. When Lincoln gave his famous Second Inaugural Address in 1865, a large part of the crowd was made up of Black men and women, many in uniform.

CCT: Eventually that right was enshrined in the Fifteenth Amendment, but as you have written, voting rights have seen both “propulsive rise and discouraging retreat.”

Waldman: There was a flowering of multiracial democracy in the South during Reconstruction. Voter participation rates among Black men were up to 90 percent. But this was followed by a terrorist backlash of white violence. By the end of the 19th century — thanks to the Jim Crow laws and revised state constitutions, as well as poll taxes, literacy tests and other barriers — there was an almost complete disenfranchisement of Black voters in the South. At the same time, immigrants were jamming into northern cities, and there were efforts to restrict the voting rights of the largely Catholic, Democratic urban population, as well as Jewish voters. In New York City one year, they moved the primary vote day to Yom Kippur.

So between the Jim Crow South and the anti-immigrant North, you had a real retreat on the promise of American democracy at the end of the 1800s. That’s a serious warning for us now — that the progress we’ve made in the last half century can also be undone.

CCT: The women’s suffrage movement, Progressive Era reforms and civil rights movement did lead to further democratization in the 20th century, culminating in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But seven years ago, in Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court voted 5–4 to strike down the key provision of the act. What has been the effect of that ruling?

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act, August 6, 1965.

Wikimedia Commons

It was working well, and it was bipartisan in its appeal. The last time the act was reauthorized, in 2006, it passed the Senate 98–0.

Along comes the Roberts Supreme Court. We all understand that Chief Justice Roberts is kind of an institutionalist, and sometimes he votes with the liberals. But he has pushed the court to be very radical in making rulings that I would argue are anti-democratic. In 2013 the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act was challenged. In the courtroom Justice Scalia said it’s nothing but a “racial entitlement.” People gasped. You can hear it on the tape.

CCT: What was the rationale in the written opinion?

Waldman: Scalia didn’t write the majority opinion, Roberts did. And he was much more decorous, basically saying, look, racism is a thing of the past; that was then, this is now. Barack Obama ’83 is President, Black voters vote at the same or higher levels than white voters in a place like Alabama, so we don’t need this anymore.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg LAW’59 wrote a famous dissent in the Shelby case, the kind of dissent that has made her a folk hero, “the Notorious RBG.” She said that’s like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you’re not getting wet. Who was right? Well, I think Ginsburg was right. Southern states immediately began implementing new voting rules that were aimed directly at Black voters and other voters of color. In Texas, two hours after the ruling, they implemented their voter ID law, the harshest in the country.

I should note, I don’t think there’s any problem with requiring voter ID. The problem is with requiring [types of] ID that lots of people don’t have. Texas’s law is sort of notorious; for example, it disallowed a University of Texas ID, but you could use your concealed-carry gun permit. In a case brought by my organization, the Brennan Center, a federal court found that the Texas voter ID law instantly disenfranchised 608,000 registered voters, who were disproportionately Black and Latino. North Carolina passed a voter suppression law that a federal appeals court ruled was crafted “with almost surgical precision” to target Black voters.

CCT: As this year’s elections approach, there’s greater apprehension about achieving a safe, just and clean process than at any time in living memory.

Waldman: The 2020 election is one of the most important in the country’s history, and we’ve long expected very high turnout. Early in the year, it already seemed clear that the system was under a lot of strain. We saw that with the Iowa caucus and long lines in places. And then, of course, along came the coronavirus. By March it became quite clear that if we didn’t take action as a country, we weren’t going to be able to have a meaningful, democratic, fully participatory election in November.

“That’s a serious warning for us now — that the progress we’ve made in the last half century can be undone.”

CCT: Let’s drill down on some of these issues, beginning with the pandemic and the arguments about mail-in ballots.

Waldman: For one, we have a massive public health crisis. If we have a second wave in October and November, a lot of people will need to vote by mail. But many states simply are not ready. Some have legal barriers, but most of them just have practical problems. In the Wisconsin primary earlier this year, people had to wait on five-hour lines to vote; their absentee ballots never arrived. They were forced to choose between their health and voting. It went from something like 250,000 people who would typically vote by mail, to 1.5 million.

My experience in the Brennan Center is that the state governments of both parties are really trying to do the right thing. What they need is help — printing ballots, having scanners to read the ballots, all the stuff that you don’t think about that you have to do to suddenly move to a vote-by-mail system.

CCT: President Trump has made it clear he wants to avoid mail-in voting.

Waldman: Yes, Trump has screamed a lot about how terrible and potentially fraudulent it is. There are many voting issues that are quite contentious, that are divided by party or race or ideology, such as voter ID requirements. Vote-by-mail was never one of them. Every political scientist who looked at it says it doesn’t help one party or another. To be very, very clear, the risk of widespread fraud from vote-by-mail is infinitesimal.

So, we’re in this weird situation where Trump is screaming that it’s rigged and there’s fraud. But he also went off script and said out loud what he’s not supposed to say; this was when Congress voted in May to appropriate $3.6 billion for states to run safe elections, and Trump said, if we have the stuff in this bill, we’ll have levels of voting so high you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.

We’ve had elections before during crises. During the 1918 Spanish flu there was an election. Lincoln was determined to hold the 1864 presidential election, even though he thought he would probably lose. But he thought it was important for democracy to show that we could run an election during a civil war. We have never had a leader of one of the political parties — let alone the President of the United States — very openly attempting to use a crisis to collapse the vote, to drive voting levels down and suppress the vote.

CCT: Even with vote-by-mail, plenty of people will be voting in person.

Waldman: Not everybody can or wants to vote by mail. So it’s very important to have in-person opportunities to vote safely. That means, especially, early voting and also better polling places with sanitation, PPE for poll workers and that kind of thing. It’s really challenging, but it’s really important. In the Wisconsin primary, the number of polling places in Milwaukee dropped from 178 to 5 because poll workers were not showing up for health reasons. In Kentucky, Louisville had to move to having one polling place for the whole city. It was the convention center, so it was big. But unless you live at the convention center, it’s not very convenient.

Also, fraud for in-person voting is vanishingly rare. The Brennan Center has done considerable research on this over the years. You are more likely to be struck by lightning than to commit in-person voter impersonation.

CCT: Intelligence agencies have warned of recurring foreign interference.

Waldman: The real risk to this election, which we should properly be focusing on, is cybersecurity. We know that Russia interfered in our 2016 election. It went well beyond hacking the Clinton campaign’s emails. They got into the voting systems in all 50 states. They got into the software of the counting centers. We don’t have evidence that they got into individual machines. But it was quite aggressive. And the director of national intelligence said last year that the lights are blinking red for it to happen again. There’s no reason to think it will just be Russia. It could be China. It could be Iran. It could be North Korea. So there’s an urgent effort to harden our systems to protect against this kind of cyberattack — everything from buying new voting machines, to improving security for the counting software. This is bipartisan, which is quite encouraging.

CCT: Are you concerned that the legitimacy of the election results might be seriously challenged or simply not accepted?

Waldman: It’s a risk that could be addressed if we act now. If there’s massive disenfranchisement because the polling places have not been made ready, and vote-by-mail is not truly available, that would call into question how free and fair the election was.

I am worried that fake claims of voter fraud pumped out by candidates and right-wing media can also help delegitimize the election. The answer has to be to make the election run well, and for the media and others to make clear that this notion of widespread fraud is a pernicious myth. For example, we probably won’t know the results on election night. The news media has an obligation to not present this as a problem or a mess or fraud, but just as how it works when you’re counting mail ballots in a pandemic.

CCT: Two of the four Presidents in this century reached office without winning the popular vote. Is it time to change or abolish the Electoral College?

Waldman: The Electoral College is absolutely broken, and yes, we should abolish it. Even in a good year it has lots of problems, because candidates only campaign in swing states, not in the states where many of the people live. If we looked at the political system of any other country and found this, we would think it was archaic and undemocratic.

There are ways to fix the Electoral College. There could be a constitutional amendment. But there’s also something called the National Popular Vote Compact, which is an agreement among states to say we will vote our electors for whoever gets the most popular votes nationwide, even if they didn’t win our state. If enough states sign up to do that, you can make the Electoral College kind of a vestigial organ.

CCT: Are there other election reforms you might propose?

Waldman: There’s an urgent need for fundamental reform of our democracy. The public has made clear that it wants reform. In 2018, for example, ballot initiatives passed all over the country to restore voting rights, for campaign reform, for redistricting reform. Dozens of members of Congress were elected on this issue in 2018. And the House of Representatives passed H.R. 1, the For the People Act, in 2019. It would be the biggest, most sweeping democracy reform law since 1960, requiring states to offer automatic voter registration all over the country and curtailing partisan gerrymandering. It would also institute public financing of campaigns for Congress. It would be a really big deal. It hasn’t been brought to a vote by Sen. McConnell. If the Democrats were to take control of the Senate as well, it would have a strong chance of being an early priority.

As a general matter, when a conservative gets so much as a pinky on a lever of power, they focus on these issues, on the rules of democracy. When Tea Party–backed candidates won control of the legislatures in 2010, the first thing they did all over the country was pass restrictive voting laws. Democrats rarely focus on these issues when they have the chance, but I think the public demand is quite strong this year. In 2014 we had the lowest voter turnout in 72 years. That was a sign of a real decay in public engagement. But in 2018 we saw the highest voter turnout in a century. So the crises of the Trump era have seemed to rekindle civic resurgence all across the board.

Former CCT editor Jamie Katz ’72, BUS’80 has held senior editorial positions at People, Vibe and Latina magazines and contributes to Smithsonian Magazine and other publications. His latest piece for CCT, “Pandemic Expert Dr. Ashish K. Jha ’92: ‘We Will Get Through This,’” appeared online in June.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu