Feminist sculptor Rachel Feinstein ’93 gets a major museum retrospective

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Feminist sculptor Rachel Feinstein ’93 gets a major museum retrospective

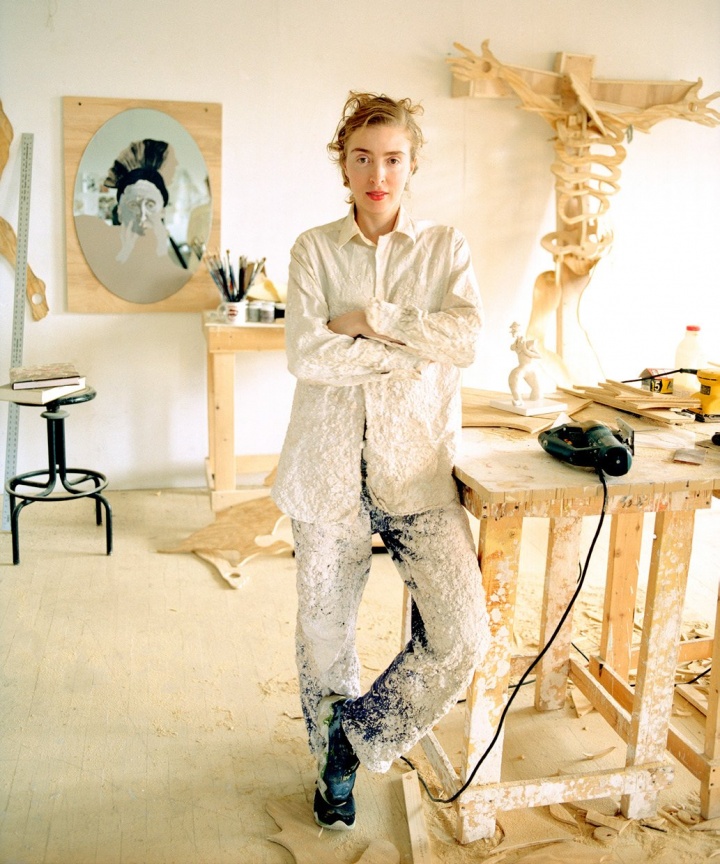

CHRIS SANDERS

Last fall, the first-floor galleries at New York City’s Jewish Museum were filled with tall, curving sculptures made from plywood and foam, enamel and resin. The ambitious structures were the work of artist Rachel Feinstein ’93; the vast retrospective, subtitled “Maiden, Mother, Crone,” was the first survey show of Feinstein’s work held in a U.S. museum.

The exhibition, and its accompanying volume, Rachel Feinstein (Rizzoli, $75), is a record of the decades the sculptor has spent exploring female archetypes. “Over the course of her 25-year career, Feinstein has confronted how women are described, seen and embodied,” writes Kelly Taxter, the museum’s Barnett and Annalee Newman Curator of Contemporary Art, who helped guide the exhibition to completion.

Feinstein isn’t wedded to a single type of material, or even to the medium of sculpture itself. “Maiden, Mother, Crone” includes video, painted mirrors, panoramic wallpaper, even a white 40-ft.-long wall relief. Feinstein has made stunning collages for New York magazine (The Seven Ages of Woman) and a castle-in-ruins runway set for Marc Jacobs’s Fall 2012 show. Underlying all these variations, though, is a single theme: women and the way they’re seen.

As a sculptor, Feinstein was forced to think about gender from the beginning of her career. “When I was just starting and said to someone that I was a female sculptor, they told me, ‘That’s really weird; that’s like a dog that can walk on its hind legs,’” she said in a recent interview with Sculpture magazine. She herself admits to nagging doubts: “I’ve always thought about how being a female sculptor is not natural, in terms of the aggressiveness and the material.” Feinstein is married to painter John Currin; a frequent theme in their media interviews is the gender-flipped aspect of the art they create. His is soft and gentle — stroking the canvas with a fine brush, in a boudoir-like studio — while her man-cave studio is noisy and filled with power tools.

To a large extent, Feinstein’s career began at the College. A Miami doctor’s daughter who had modeled as a teenager, she knew she wanted to be an artist, but had little experience with or knowledge of art history. She started out pre-med (thanks to her parents’ urging), but she soon changed direction to pursue studio art, and studied with influential instructors like installation artist Judy Pfaff. She found a group of fast friends — intimates whom she still calls her “art clan” — and started exploring the funkiest reaches of Downtown. Feinstein credits her time at the College with giving her something essential to her art: a sense of possibility. “I don’t know if I would be where I am today if it wasn’t for Columbia and Judy Pfaff,” she told CCT.

The art that Feinstein created at that time could be hard-charging and forceful, drawing energy from early-’90s, third-wave feminism. Her sculpture Ultimate Woman (1993) shows a woman on all fours, with red-rimmed apertures reminiscent of gaping wounds on her back. Someday My Prince Won’t Come, her first performance art piece, featured Feinstein swinging inside a huge welded hoopskirt, as red wine gradually spilled over her clothes. At a 1994 Exit Art group exhibition, Let the Artist Live, she posed as a drowsing Sleeping Beauty, but her golden-haired princess was humped by a grotesque castle as she lay in bed. She met Currin around that same time.

Her “bad-ass” single life — and the artistic style that went with it — came to an end. Twenty-six years later, the two artists share a townhouse, family life and to some degree, an artistic mindset. Importantly, Currin taught Feinstein that older European art could be an invaluable source of ideas. Feinstein’s creative process now often begins with research in her bookshelves, or at the Strand Bookstore. (“Maiden, Mother, Crone” was inspired by the book Maids, Madonnas & Witches: Women in sculpture from prehistoric times to Picasso, with photographs by Andreas Feininger.) The later work shown at The Jewish Museum explores female archetypes derived from examples of old European fine and decorative art, like madonnas, German woodcarvings, even Meissen porcelain figurines.

Feinstein herself, having passed the maiden stage, has embraced the role of mother to the couple’s three children. But far from dreading the approach of her “crone” years, she seems to be looking forward to a late-stage artistic flowering. In an interview on Bloomberg TV last fall, flanked by men in business attire, she is luminous and charismatic in bright lipstick and a vividly colored dress. Historically, she says, female artists like Louise Bourgeois, Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Martin honed their skills later in life, once the biological imperative to reproduce was gone. Women artists get “more marketable after menopause,” she says with a smile. “It seems that you just come into this strength and power as you get older.”

Left: Unicorn or “H,” 2002. Fabric, resin, plaster, foam, wood, enamel, 40 x 73 x 31 in. In exhibition Tropical Rodeo, Le Consortium, Dijon, 2006. Private collection.

Right: Old Times, 2005. Stained wood, 97 x 43 x 23 in. In exhibition Tropical Rodeo, Le Consortium, Dijon, 2006. Collection of Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn and Nicolas Rohatyn.

Adam and Eve, 2007. Wood, stain, hardware, 84 x 45 x 41 in. Collection of Mima and César Reyes, San Juan.

Fat Friend, 2000. Wood, epoxy, Sculpey, plaster, enamel, gold leaf, 60 x 49 x 32 in. Collection of Mark Fletcher and Tobias Meyer.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu