|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COVER STORYBarack Obama ’83Is He the New Face of The Democratic Party?By Shira Boss-Bicak ’93

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Obama burst onto

the national political scene by delivering a rousing keynote

address at the Democratic National Convention in Boston. |

Barack Obama ’83 was sworn in this month as the sole

African American in the U.S. Senate, and only the fifth

in history. He is the highest-ranking African-American elected official

in the United States.

But that’s not all he is being celebrated for. After delivering an eloquent, energizing keynote address at the Democratic National Convention last July, Obama became a national figure whom some are calling the future of the Democratic Party. Politicians from both sides of the aisle acknowledge that he has a natural ability — partly stemming from his biracial and itinerant background — to connect with a range of people, to bring opposing sides together and to move policy forward.

“He’s a rare package of brains, values and personality,” says John Bouman, an advocate who has worked with Obama on policy issues. “What you see is the real deal. It’s a good break for all of us that he chose politics.”

A year ago, Obama was a little-known state senator from Illinois elbowing a half-dozen other candidates for the Democratic nomination to run for the U.S. Senate. Few people outside of his home state had any reason to know of, or care about, “the skinny kid with the funny name,” as he likes to describe himself.

Then, last March, he won the nomination, and national press coverage soon followed. Early articles included a feature in The New Yorker, and a long Salon.com essay about him written by his friend, novelist Scott Turow, heralding “The new face of the Democratic Party — and America.”

The Kerry campaign took notice, and tapped Obama to deliver the coveted keynote address at the party’s convention. That really did it: The media wanted to know what was so special about Obama, and when they found out — Obama related his personal story within his convention address, and his message of unity resonated with people across the country — the attention escalated like a skyscraper’s express elevator.

|

|

|

| Obama has been described

as a one-man melting pot and likes to say, “My name

comes from Kenya, and my accent comes from Kansas.” |

Television and radio interviews, magazine and newspaper profiles, hundreds of guest appearance invitations and national fan mail followed. Nobody was making quips about his name anymore, except for Obama himself, who continued to relish a joke he tells about how people mistake his name for Alabama or “Yo Mama,” and David Letterman, who featured a Top-10 list of “Ways to Mispronounce Barack Obama.”

Obama became so popular, and so far ahead in the general election polls, that he contributed some of his campaign time and money to boost the cause of fellow Democratic candidates. At 43, with a political career that included only eight years as an Illinois state senator, Obama was catapulted to national stardom and became the new darling of the Democratic Party.

And it is not only the Democrats who are interested in this “rock star politician,” as he has been called. The day after Obama won the Senatorial election, President George W. Bush called him, announcing, “You’re one articulate fella!” The two ended up chatting for 10 minutes, according to one of Obama’s aides. Two weeks later, Obama accepted an invitation to the White House and had breakfast with President Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney and political strategist Karl Rove.

“Here’s a guy who hasn’t served a day in the Senate, and I just saw an ‘Obama ’08’ [for President] button,” says David Axelrod, Obama’s friend and media consultant. “It’s out of control.”

Other politicians might be envious of the attention Obama is receiving, but those who have worked with him say his newfound popularity is deserved. “This is a guy who’s not just the product of a PR campaign,” says Dick Devine, state’s attorney for Cook County, which includes Chicago. “He has real intelligence and real substance.”

“He was not a traditional Democratic candidate, and he won’t be a traditional senator,” says Valerie Jarrett, Obama’s finance committee chair. “He has the ability to reach across the aisle and an extraordinary ability to connect with people: rich, poor, black, white, farmers and CEOs. That has a lot to do with how he was raised.”

Obama embodies diversity. Associated Press reporter Christopher Wills dubbed him a “one-man American melting pot.” As Obama liked to say when introducing himself to crowds on the campaign trail, “My name comes from Kenya, and my accent comes from Kansas.”

|

|

“You’re one articulate fella.” — President George W. Bush |

Obama was born in 1961 in Hawaii to a white woman from Kansas and a black man who came from Kenya to study at the University of Hawaii, where the two met in 1960. They were married for a brief time. His father, also named Barack, went on to graduate studies at Harvard and then back to Kenya, where he had two other families, one with a Kenyan wife from before his marriage to Barack’s mother, and another with a second American wife. Obama saw his father one more time, several years later, and grew up idolizing him. Obama’s Midwestern mother nurtured her son’s appreciation of and identification with black culture.

Obama, who is married to an African-American woman from Chicago, describes himself as an African American, and says he is “rooted in the black community but not limited to it.”

People have been asking him recently, if he’s half white, why does he describe himself as an African American? He responds that the term African American denotes one has two sides to his heritage. “And I would broaden that and say, by definition if you’re an American, you’re a hybrid person,” Obama said recently on the television program Charlie Rose. “All you have to do is look at these white suburban kids who are wearing baggy pants and listening to Snoop Dogg to get a sense of how cross-pollination has taken place between cultures.”

Obama’s heritage goes beyond black and white. When he was 6, his mother remarried, to an Indonesian student she met at the University of Hawaii, and the family moved to Jakarta, where a half-sister, Maya, was born. After spending two years in a Muslim school and two years in a Catholic one, Obama was sent back to Hawaii to be raised by his Kansan grandparents, a furniture salesman and a bank employee who lived in a small apartment.

Obama went by the name Barry and got on the wrong track as an adolescent. He shunned school, spent much time playing basketball and turned to drinking and smoking marijuana, even experimenting with cocaine. Obama described this period of his life in his 1995 memoir, Dreams From My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. “I guess you’d have to say I wasn’t a politician when I wrote the book,” Obama told The New Yorker. Now that the transgressions are public information, he makes the best of the disclosure. “I wanted to show how and why some kids, maybe especially young black men, flirt with danger and self-destruction,” he said.

On the eve of delivering his keynote address at the Democratic convention, Obama explained on the television program Meet the Press, “Fortunately, I think that my family had such strong values, very much Midwestern values, that I pulled out of that funk, and was able to succeed.”

|

|

|

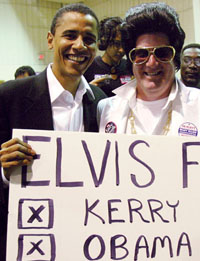

| Obama meets

a supporter during a campaign visit to Chicago's suburbs the

week before the election. |

Obama says he was still goofing off for the first two years of college, which he spent at Occidental in Los Angeles. He continued to play basketball, which friends say he is still quite good at, and was involved in other organized activities. He also spent “a lot of time having fun.”

He changed course junior year when he transferred to Columbia. “I realized I wanted to be in a more vibrant, urban environment,” he says. As a transfer student, he didn’t receive housing, so lived off campus in various makeshift arrangements, such as living in one bedroom of a three-bedroom apartment, and renting a sixth-floor walk-up with slanting floors on the East Side, “just north of gentrification,” as he describes it.

As he pursued a political science degree, specializing in international relations, Obama says he was somewhat involved with the Black Students Organization and participated in anti-apartheid activities. “Mostly, my years at Columbia were an intense period of study,” he says. “When I transferred, I decided to buckle down and get serious. I spent a lot of time in the library. I didn’t socialize that much. I was like a monk.”

Obama says it is difficult to separate his college experience at Columbia from the urban experience of living in New York City, and his memoir offers little about his time on campus. One noteworthy event during Obama’s college years, however, was his learning in 1982 of his father’s death from a car accident. It was not until years later, however, when Obama’s older half-sister visited him in Chicago, that he learned how inaccurate his image of his father had been. After working for an American oil company in Kenya and then for Kenya’s Ministry of Tourism, the economist fell out of favor with the government, was blacklisted from finding work and was socially outcast. He became a heavy drinker, turned abusive to his American wife and eventually was destitute, borrowing money from relatives for food, as Obama describes his sister’s account in his memoir.

“All my life, I had carried a single image of my father … The brilliant scholar, the generous friend, the upstanding leader. That image had suddenly vanished,” Obama wrote. “Replaced by … what? A bitter drunk? An abusive husband? A defeated, lonely bureaucrat? To think that all my life I had been wrestling with nothing more than a ghost! The king is overthrown, I thought. … Whatever I do, it seems, I won’t do much worse than that, I thought.”

Upon graduating from Columbia, Obama attempted a career as a community organizer. He wrote that when classmates weren’t sure what that was, he didn’t have a sufficient answer for them. “Instead, I’d pronounce the need for change,” he wrote. “Change in the White House, where Reagan and his minions were carrying on their dirty deeds. Change in the Congress, compliant and corrupt. Change in the mood of the country, manic and self-absorbed. Change won’t come from the top, I would say. Change will come from a mobilized grass roots.

“That’s what I’ll do, I’ll organize black folks. At the grass roots. For change.”

Obama wrote letters to community organizations all around the country asking for a job, but received no positive responses. He ended up working as a research analyst at a consulting company before being promoted to financial writer. “I had my own office, my own secretary and money in the bank,” he says in his book. But he left to pursue his original goal of activism. For six months, Obama carried on another letter-writing campaign seeking a job and worked with an environmental group to encourage City College students to recycle. At last, he landed a job with a nonprofit in Chicago.

Obama drove to his new home, not knowing anyone there, and worked for three years in low-income neighborhoods helping churches create job training programs and advocating school reform.

In his late 20s, Obama attended Harvard Law School, where he received national publicity when he became the first African-American president of Harvard Law Review. Publishers contacted him about telling his life story, and he began to work on his memoir, which was published in 1995. It had a 15,000-copy print run but didn’t win a large readership and soon slipped out of print. Last summer, in the midst of Obama-mania, stray copies started selling on eBay for 10 times the original cover price. In August, a division of Random House reissued it in paperback, and the book promptly climbed to The New York Times paperback nonfiction bestseller list.

|

|

“He has real intelligence and real substance.” — Dick Devine |

Obama spent one summer during law school as a summer associate in Chicago at the prestigious law firm Sidley & Austin. His mentor there was a first-year associate, Michelle Robinson, a Princeton and Harvard Law graduate who, despite resisting his initial advances, married Obama in 1992, the year after he graduated from law school.

“He could have written his ticket anywhere and made a fortune in industry or at a law firm,” says Axelrod, the media adviser. Instead, Obama went the route of lower-paying but more gratifying work, as did his wife. “I always felt that the value of a really good education is you can take more risks,” Obama said in November on Charlie Rose. “Ultimately, if I really need a job, if I’ve got to pay the bills, I’m going to be able to find one.”

As a public-interest lawyer in Chicago, Obama worked on cases involving voting rights, employment discrimination and low-income housing. He also took a position as a lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School, where he taught constitutional law and a seminar on civil rights, until taking leave a year ago. “They’d love nothing better than to have him as a tenured professor,” says Abner Mikva, a former Congressman and a friend and colleague of Obama’s at the University of Chicago. “His student ratings are off the charts.”

In 1995, at his friends’ urging, Obama ran for political office. “I think that the reason I got into politics was simply because I saw the law as being inadequate to the task,” he explained on Charlie Rose. “It’s very difficult to bring about social change at this point through the courts. [And] community organizing was too localized and too small.”

In 1996, Obama won the race for state senator representing Illinois’ 13th district, which includes Hyde Park, the South Side and the University of Chicago. Unfortunately, it was at the cost of some political sore feelings. He had entered the race because the would-be incumbent, Democrat Alice Palmer, decided to run for a Congressional seat rather than for re-election as a state senator. Obama initially had her blessing to run for her state senate seat. When she lost the Congressional race, however, she decided to run for re-election in the senate and asked Obama to step aside. He refused, and she withdrew. Obama later called it “an unfortunate situation.”

Obama admits to a fiercely competitive streak, yet he hasn’t made any apparent enemies. In addition to being personable, he is tall and athletic, with a dazzling smile. In Springfield, the seat of Illinois politics, he joined in a regular 6:30 a.m. basketball game and took part in a long-running bipartisan poker game with other legislators. He has taken up golf in recent years and honed his skills so as not to be beaten too easily, an associate says. He is known for remembering things, large and small, and he doesn’t like to disappoint anyone. He is a charmer, for sure, whose only obvious defect might be that he hasn’t been able to give up smoking (cigarettes, that is).

|

|

|

Obama speaks at

the Chicago Federation of Labor's rally on Labor Day at Navy

Pier. |

Obama is a longtime member of the congregation of Trinity United Church of Christ. His pastor was the first person he thanked by name in his election night victory speech last November. Obama’s wife is the director of the office of community affairs at the University of Chicago Hospitals, and they have two daughters, Malia (6) and Sasha (3). Obama says that his favorite leisure pursuit is “rolling on the floor with my 3-year-old and 6-year-old and spending time with my family.” He takes time out for movies and is “looking forward to the time when I’ll again be able to read a book, and not just a policy brief.”

As a state senator, Obama chaired the Public Health and Welfare Committee and championed a number of social justice issues. One of his first efforts was working on the state’s implementation of the federal welfare reform of 1996. “At the time, he was close to being a freshman, and was in the minority in the state senate, and yet he managed to be extraordinarily important and influential on that issue,” says Bouman, advocacy director of the Shriver National Center on Poverty Law in Chicago. Obama subsequently sponsored a bill, which passed into law, to require the state to share its data on the welfare program with researchers. (Some states won’t disclose such data.) “It isn’t all that sexy, but if you’re a serious, thinking person who cares about public policy as well as politics, it was a forward-thinking thing to do,” Bouman says.

The state senator also took on the issue of curbing racial profiling, advocated expanding health insurance coverage for the poor, and sponsored a bill to require videotaping police interrogations in homicide cases. Obama was among the lawmakers recruited by prosecutors to reform the juvenile justice code. “He was one of the few legislators who had 1) read the proposed legislation, 2) understood the major issues and 3) was willing to sit down and discuss the substantive points,” says Devine, Cook County prosecutor.

Obama’s agenda is liberal. He’s not interested in sacrificing his values, nor will he be swayed by public opinion polls, those who work with him say. Yet he is a pragmatist. Bouman says Obama is the man to manage the situation “when there are competing interests and entrenched opinions or real battle lines drawn. Some things got done in Illinois because Barack got the sides to sit down and talk to each other and hammer something out.”

On Meet the Press after the election, host Tim Russert asked Obama if it is possible to negotiate on divisive issues such as abortion. “Well, look, I think some are more difficult than others,” Obama replied, and went on to give an example of finding common ground. “There’s no doubt that on the issue of abortion, oftentimes it’s very difficult to split the difference,” he said, “although we can agree on the notion that none of us are pro-abortion, and all of us would like to see a reduction in unwanted pregnancies, for example, and we could focus on those issues.”

Obama criticizes the nastiness of politics, trumpets positive messages and likes to say that Americans are ready for politicians who “can disagree without being disagreeable,” a phrase he adopted from the late Illinois Senator Paul Simon.

Not many skeletons have been exhumed from Obama’s closet. Salon.com’s “Muckraker” columnist went on a mission to harvest some dirt on Obama’s environmental record, but ended up declaring, “This guy is a bona fide, card-carrying, bleeding-heart greenie.” Despite openly fretting about his family’s financial stress, Obama apparently hasn’t accepted any side payments from special interests. “He’s absolutely clean,” Bouman says. “Nobody can pay for as much as a Coke for him, and that’s not the culture in Springfield, Illinois. It’s pretty much no holds barred.”

|

|

“I got into politics because I saw

the law |

Raising money for campaigns, which includes the necessity of appeals to personal friends and deep-pocketed community figures, was until recently a trying experience for Obama. “He wasn’t comfortable with the process,” Mikva says, “but he learned to be really comfortable with it.”

Not, however, before insufficient funds was one factor that sank a bid for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 2000, against the advice of some more experienced politicians, Obama challenged the Democratic incumbent, Bobby Rush. “A lot of people were frustrated with the incumbent and came to Barack and asked him to run,” says Dan Shomon, who managed that campaign. They raised $535,000, not enough for television ads, Shomon says. Obama was stomped in the primary; he said he learned from the experience, and went back to the state senate.

Two years later, Obama announced he was running for U.S. senator. The incumbent, Republican Peter Fitzgerald, was retiring. It was a long shot. “The announcement was received respectably, but people didn’t believe we could win,” Axelrod says. “There were many turns of fortune in this thing.”

The first challenge was fund raising. “It was an uphill battle at the beginning,” Jarrett says. “State senate is very different from statewide office.” Obama didn’t have much name recognition outside of his district, and with a crowded field of seven candidates in the primaries, there were other places for Democrats to send their money. Even many of those who did contribute, Jarrett says, did so saying that while they wanted to support him, they didn’t think he could win the race. “It was discouraging at times, because people who should have been with us — funders, labor and political leaders — weren’t with us,” Axelrod says.

Among the competitors were a popular state comptroller and a businessman who spent $29 million on his campaign. Obama raised $6 million in the primary, enough to get on TV and introduce himself to a broader constituency. His message got across. On March 16, he won the primary with 53 percent of the votes — more than his six rivals combined. That’s when the national attention started and money began to flow more easily; the campaign raised another $15 million for the general election.

“Every single break that Obama didn’t get in the Congressional race, he got in the Senate race,” says Shomon, political director of the Obama campaign. “There were a lot of factors aligned to our benefit.”

One big break came in June, when Obama’s would-be formidable Republican opponent, Jack Ryan, a wealthy former Goldman Sachs partner, withdrew from the race amidst news of a sex scandal. That sent Republican Party leaders scrambling to find a replacement candidate, and Obama later joked on The Late Show With David Letterman that the Republicans “couldn’t find anyone out of the 12 million people in Illinois to run against me.” Ryan was replaced by Marylander Alan Keyes, an African American who worked in the Reagan administration and has run for president.

More good fortune came in the form of the Kerry campaign inviting Obama to deliver the convention’s keynote address. “They wanted somebody to represent the diversity of the party, and people knew he was a good speaker,” Shomon says.

|

|

|

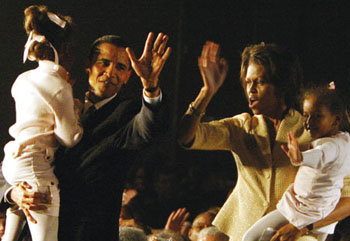

| Obama and his wife,

Michelle, wave to supporters during the Wheaton Independence

Day Parade. |

Obama is a natural and polished orator. What he has had to work on, those who know him say, are his one-on-one connections. During his eight years in the state senate, Obama spent more time with his constituents and learned to be an attentive listener, they say. Those skills were essential in connecting with statewide voters during the Senate campaign. Obama successfully appealed to inner-city blacks and suburban professionals as well as downstate farmers and factory workers. When he reached out to the state’s rural areas, he was able to relate to the farmers there because “those folks were very much like the grandparents from Kansas who raised him,” Axelrod says.

Obama drafted the convention speech on paper during two nights in a hotel room during the campaign. He writes all of his speeches, bills and other important documents, according to Shomon. When Obama finished the draft of the speech, he faxed a copy to Axelrod, who says, “I was reading it and handing each page to my wife, and my mouth was agape, because it was beautiful and profound. How many people in public life can write like this?” Axelrod says the consultants and the Kerry camp recommended few changes, and 80 percent of the final speech was the same as the original draft.

It was a hit. What first struck the audience was Obama’s family’s story. He said his foreign father “grew up herding goats, went to school in a tin-roof shack.” He described his paternal grandfather working in the kitchen as a servant to the British. Obama talked about his maternal grandfather “working on oil rigs and farms through most of the Depression,” enlisting to serve in World War II the day after the Pearl Harbor attack and coming home after the war to study on the G.I. Bill.

“[My parents] would give me an African name, Barack, or ‘blessed,’ believing that in a tolerant America, your name is no barrier to success,” he said. “They imagined me going to the best schools in the land, even though they weren’t rich, because in a generous America you don’t have to be rich to achieve your potential.”

|

|

“The American people are looking for common-sense, practical solutions.” |

Obama delivered a positive message of diversity and unity and described “the true genius of America” as being “that we can say what we think, write what we think, without hearing a sudden knock on the door. That we can have an idea and start our own business without paying a bribe. That we can participate in the political process without fear of retribution, and that our votes will be counted, at least, most of the time.”

He addressed “fellow Americans, Democrats, Republicans, Independents … ” His attacks on the Bush administration were descriptive rather than combative. He said, for instance, “If there’s an Arab-American family being rounded up without benefit of an attorney or due process, that threatens my civil liberties.”

Obama said he had a message for “the pundits [who] like to slice and dice our country into Red States and Blue States … We worship an awesome God in the Blue States, and we don’t like federal agents poking around in our libraries in the Red States. We coach Little League in the Blue States and yes, we’ve got some gay friends in the Red States. There are patriots who opposed the war in Iraq and there are patriots who supported the war in Iraq.”

The message seemed to work, for the Democratic Party and, especially, for Obama himself. “He was shot out of a cannon,” Axelrod says. Seemingly every media outlet wanted to do a story about him, his ratings in his senatorial race jumped and he received thousands of invitations to events and to podiums. He became, while still running for his first national office, a national celebrity. “He’s really on stage 24/7 now,” Shomon says. “He can’t go to the bathroom without someone recognizing him.”

Friends and supporters have grown mildly concerned at the amount of attention that Obama has received. “He’s risen so fast that it’s very hard, for anyone, not to inhale some of this marvelous national press he’s been getting,” says Mikva, his friend and political mentor. “If you start to believe that you can’t do wrong and that you walk on water, you stop asking for advice, and it will be your downfall.”

Mikva and others close to Obama say, however, that they believe he can handle it as well as anyone. And if he should stumble over his ego, his wife can be relied upon to prune it.

“I’ve been blessed with a relatively calm, steady temperament and am someone who reminds myself that it’s never as good as it seems and never as bad as it seems,” Obama says.

|

|

|

| Obama, his wife, Michelle,

and their daughters wave to supporters following his victory

speech at the Hyatt Regency in Chicago on election night. |

With a campaign motto of “Yes we can,” Obama won 70 percent of the vote. He likes to point out that he shared one million voters with Bush, confirmation of his theory that the Red and Blue America characterization is an oversimplification and that many individuals are conflicted about which party to identify with. “The American people are a non-ideological people,” Obama said after the election on Meet the Press. “They very much are looking for common-sense, practical solutions to the problems that they face.”

Obama is eager to solve problems, yet realistic about his place in the Senate. “I rank 99th in seniority and I’m in a minority party that took some hits in the last election,” he says. “There’s a large gap between the power that I’ll wield in Washington and the enormous needs that I see in Illinois, such as healthcare, lack of well-paying jobs and need for education reform.

“What I do expect to be able to accomplish is where there are issues that everyone agrees need to be worked on, I’ll be able to insinuate myself into the debate and see that voices that otherwise would be left behind are introduced into those negotiations.”

As for speculation that he could be the country’s first black president, Obama says that he will not run for anything in 2008. He is quick to temper high expectations and scrying about his lofty political future with quips about how he doesn’t yet know where the Senate bathrooms are, and how he’ll be “sharpening pencils and scrubbing floors” for the first few years.

“He says that the first thing is for him to learn to be a first-rate senator,” says Jarrett, the finance committee chair. “If that leads to something else one day, fabulous. But first things first.”

Contributing writer Shira Boss-Bicak ’93

is writing a book about money that tells the Joneses' side of the

story, showing that we are all better off with more honesty and

contentment and less comparison and envy. Tentatively titled The

Money Next Door, it is scheduled to be published next year by

Warner.

| || | || |

CCT Home |

|

|

CCT Masthead |