|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FEATURESOriginal Cable GuyBob Rosencrans ’49 Changed the Way We Watch TelevisionBy Jonathan Lemire ’01

Imagine settling down in front of your television, remote in hand, and flipping channels. As you race through the dial, you realize that you cannot watch Stephon Marbury and the Knicks on MSG. Or Tony Soprano on HBO. Or OutKast videos on BET. Or even the day’s Congressional hearing on C-SPAN. Fortunately, Bruce Springsteen’s prophecy of “57 channels and nothing on” (or, in some markets, more like 257 channels) has not come true, thanks in large part to Bob Rosencrans ’49, who helped to create several of today’s most popular networks and paved the way for countless more. Indeed, Rosencrans was one of the original “Cable Guys.” Couch potatoes everywhere should be grateful. “He is much more important to what has happened in cable TV than he will ever get credit for,” says Brian Lamb, CEO of C-SPAN, which Rosencrans helped get off the ground. “There is not a promotional bone in his body, and he is about the classiest, most decent person I’ve ever worked with.” The second of two sons, Rosencrans inherited his entrepreneurial genes from his parents. His mother, Eva, was a talented dress designer with a flourishing Seventh Avenue shop, while his father, Alvin, was a successful importer who specialized in ladies’ hats. Both were immigrants (Eva from Russia, Alvin from Austria) who came to the United States with next to nothing; the New York City household that Rosencrans was born into in 1927 was one where hard work and creativity were the rules of thumb. Moving to the suburbs before the term had been invented, the Rosencrans family relocated during the Depression to Woodmere, Long Island, where Rosencrans was enrolled in a small, ethical culture school. However, his near idyllic life of playing sports and studying hard was harshly interrupted in February 1945 when his family was devastated by the news that its oldest child, Herbert, was killed in the war in Germany. Rosencrans immediately enlisted in the Air Force, though he was kept stateside during the end of the war. He returned home, realizing that one of the most important decisions of his life was already made for him. “I had thought of leaving the area for college and enrolling in Dartmouth, but my brother’s death changed that,” Rosencrans says. “I wanted to be closer to home and still get a great education, and Columbia College was the ideal fit for me.” “With a shortage of students because of the war, the College was desperately trying to fill the Class of ’49,” he says. “I remember walking up the steps of Low Library, shaking hands with the dean of admissions, and I was in.”

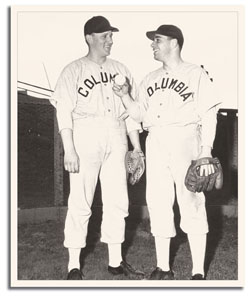

An economics major, Rosencrans signed up for a professional program in which he took three years of classes in the College and the fourth at the Business School. He fondly remembers several classes he took on Morningside Heights and singles out American history professor Dwight Miner ’26’s famous lectures on Teddy Roosevelt. Miner would act out significant portions of the Bull Moose’s career, complete with costumes, and create such a buzz among students that they would sit in non-air-conditioned classrooms for an hour afterward talking about what they had experienced. “It was like a stage show, and [Miner] was both teacher and performer,” Rosencrans remembers, laughing. “He affected a lot of students, and certainly me.” A right-handed pitcher on the school’s “middling” baseball team, Rosencrans graduated with no clear idea of what to do next. First came a brief stint in retail at Bloomingdale’s, followed by an even briefer stint at Macy’s, neither of which satisfied Rosecrans’ creative impulse. After a year in the military reserve during the Korean War, and then a second year at the Business School (he earned a master’s degree in 1952), Rosencrans was ready for a change, and a challenge. A phone call from a family friend provided him with that opportunity. Box Office Television (BOT), with the backing of the legendary Sid Caesar, wanted to produce programs to give movie houses a chance to compete with the suddenly booming home television industry. Harlem Globetrotter games and Saturday afternoons of Notre Dame football highlighted BOT’s roster, but its bread-and-butter events were industrial shows (precursors to infomercials) often used to trot out new products in theaters in major cities. Rosencrans took the wheel — literally — for a show that rolled out the Edsel and prominently featured Robert McNamara, then a Ford wunderkind and later the very-controversial Secretary of Defense. “McNamara and the Edsel,” Rosencrans recalls, chuckling at the thought. “Good thing I don’t believe in omens.” Not long afterward, Rosencrans rubbed shoulders with another corporate pitchman-turned-politico: General Electric spokesman Ronald Reagan. “He was a charming guy, and we got along nicely,” Rosencrans noted. “But no one among us would have ever guessed he’d end up where he did.” In 1956, BOT was purchased by TelePrompTer, which used its new acquisition — and Rosencrans, who was named v.p. — to distribute closed-circuit broadcasts of sporting events, mostly prize fights, to theaters across the country. Before one of those fights, Rosencrans received a call from Bill Daniels of Casper, Wyo., who asked to broadcast the bout on his cable system. Rosencrans remembers his reaction. “Cable system? What’s a cable system?” he asked. The answer would change his career. After negotiating to get the fight’s signal beamed from Denver to Casper, Rosencrans began to study what Daniels had deemed “the business of the future.” Rosencrans liked what he saw. “At the time, cable was used almost exclusively in small towns and rural areas, since big cities used the network broadcast signals,” he says. “I wasn’t satisfied with the closed-circuit industry, and I knew this was where I wanted to go.”

Rosencrans put together a team of investors to purchase a small cable system in Washington State in 1962 for the bargain-basement price of $580,000. The system, which was based in towns along the Columbia River near the Oregon border, was dubbed Columbia Cable Systems. (“Sure, a slight nod at alma mater,” Rosencrans says.) Others followed: Systems in small towns in Arizona, Oregon and California were snatched up, and “all of a sudden, we had a company,” Rosencrans says. Multi-million-dollar agreements in Florida and Texas were next. The company went public in 1969. Columbia Cable suddenly was a player, and others noticed. After a potential merger with Viacom fell through, United Artists Cablevision — a subsidiary of United Artists Theaters — came calling with a deal that created a 135,000-subscriber company, the 10th-largest in the country. It had been a whirlwind 10 years, but Rosencrans was far from satisfied. A lifelong sports fan whose passion was the New York Giants baseball team (he attended the one-game playoff in 1951 that featured Bobby Thompson’s dramatic home run), he was intrigued with the idea of bringing live sporting events into people’s homes through cable. Though armchair quarterbacks today view the ability to watch sports 24-7 on cable as a birthright, it was then seen as a risky proposition. But, using his newly-acquired New Jersey systems as a starting point, Rosencrans approached the brass of Madison Square Garden and walked away with a deal to broadcast 82 Knicks and Rangers games a season. A new era was born. Chris Berman, you’re welcome. “For the first time, everything from hockey to basketball to dog shows was on cable as basic programming,” Rosencrans says. “We sold national advertising and our format became the industry standard for everything from ESPN to CNN.” His eyes open to the programming possibilities of cable, Rosencrans gave the green light to participate in the satellite broadcast of a heavyweight boxing match scheduled for September 30, 1975. The classic “Thrilla in Manila” between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier was broadcast on the then-fledgling HBO, via satellite from United Artists-Columbia. Rosencrans threw the switch to get it started. “When you looked at the close-ups, the fighters looked like they were in the next room, the picture quality was that extraordinary,” he says. “We knew we had a winner. We knew this was a big day.” (He was right. The fight’s success convinced Time, Inc., to hold off on plans to shut down HBO.) Inspired, Rosencrans wanted to broadcast his own Madison Square Garden events by satellite, but he realized that cable needed to offer subscribers more than pay movies and sporting events. Working with Joseph Cohen, an executive at MSG, Rosencrans came up with a plan that mixed fees and advertising, which became the model for cable networks from coast to coast. In fall 1977, their dream was realized and MSG Sports Network launched as the nation’s first satellite-delivered basic cable service.

“No matter who had which idea, Bob had everyone feeling like they had come up with the idea,” Cohen told the audience at the annual dinner of the Cable TV Hall of Fame, when Rosencrans was inducted four years ago. “He had a wonderful way of making you feel good about the venture you were in.” But the network didn’t use all of its transponder time, so Rosencrans saw room for expansion and diversity. Calliope, a block of children shows for daytime television, was up and running before long, and the network later merged with MSG and adopted a much more familiar name: the USA Network, still one of cable’s most successful channels. Then, an opportunity arose to create what Rosencrans would years later deem “the best thing I’ve ever done.” Lamb, then Cablevision magazine’s Washington, D.C., bureau chief, pitched an idea to a cable conference about a nonprofit network that would provide gavel-to-gavel coverage of the House of Representatives. No talking heads, no analysis, just the speakers on the floor, and the chance for voters to decide for themselves. No one was interested. Except Rosencrans. He wrote the first check ($25,000), and then rallied the cable industry for support. “Out of the 40 industry leaders, only Bob said he liked the idea, and he got right behind it,” says Lamb. “And, for me, the network became a success only years later, when C-SPAN was picked up on the cable system that Bob got at home, and he called me and said he enjoyed the hearing we had on that night.” The idea was met with resistance by broadcast and local channels, which held tremendous influence in Congress and the FCC, but meetings with the House leadership, including legendary Speaker Tip O’Neill (D-Mass.), at which Rosencrans and Lamb pledged that the new network would be non-political, paved the way for its inception. “Bob saw the value in having an unfiltered flow of information about policies and politics available to the public,” Lamb says. “Without his help, that wouldn’t exist.” Today, C-SPAN has two sister networks, C-SPAN2 and C-SPAN3, and provides unmatched access to Congress, election campaigns and events such as the September 11 Commission hearings. A self-described political junkie, Rosencrans serves on the network’s board as chairman emeritus. Mindful of the need for variety on the dial, Rosencrans followed up C-SPAN with something different: He gave a young businessman a few hours of network time on Friday nights for programming geared to young African Americans. That programming evolved into Black Entertainment Television (BET). The businessman was Bob Johnson, now owner of the NBA’s Charlotte Bobcats. The cable game, however, was growing cutthroat. By 1984, big money had crept in, major corporations (G.E., Getty) were snapping up networks and sports leagues were selling their broadcast rights to ESPN. UA-Columbia was caught in the middle. Rosencrans was assigned the thankless task of dividing his company into two, one half for United Artists, the other to Toronto-based Rogers Cablevision. He grew unhappy. “We were entrepreneurs but were treated like employees, and I wouldn’t have it,” he recalls. “It got to the point when, on the eve of consummating a profitable merger that I created, they [Rogers] fired me.” The company’s method was almost unheard of in its coldness: Rosencrans was paged to a pay phone while he was at a charity dinner and given the news. His friends and allies were furious and demanded retribution. He took a different approach. “It was the best thing that ever happened to me,” he says. “I was free again.” Namely, free to form a new company, Columbia International. With several of his long-term associates along for one last ride, Rosencrans spent the next decade skillfully navigating the expanding world of cable and media, purchasing cable systems throughout the country.

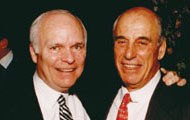

In 1995, he said goodbye, selling Columbia to TCI, Jones Intercable and Continental Cablevision for an estimated $600 million. Surprising no one, Rosencrans had gone out on top. “Columbia International gave me a chance to finish my full-time career in a manner that was true to my principles,” he says. “I couldn’t have asked for more.” Stepping away from the cable industry didn’t mean retirement for Rosencrans. He’s stayed active with C-SPAN and its “Public Affairs” publishing company and works tirelessly with several charities in Greenwich, Conn., where he and his wife of 48 years, Marjorie, make their home. And, of course, there’s always time for his four adult children and his 11 grandchildren, one of whom is a first-year student in the College. “I had nothing to do with it,” Rosencrans says of his granddaughter following him to Morningside Heights. “She doesn’t need my help at all.” But she might bump into him on campus. Rosencrans is an active alumnus who is a member emeritus and former chair of the College’s Board of Visitors. During his tenure as chair, his mission was to ensure that the College stay at the center of University life. “I came in during a time when there seemed to be a diminution of the College’s role at Columbia,” says Rosencrans. “We did our part, and I’m so encouraged now by the direction in which Dean Austin Quigley and President Lee C. Bollinger are taking the school.” Honored for his work and vision at his alma mater and in his profession, Rosencrans received a pair of awards he describes as “humbling” in 2000: the John Jay Award for distinguished professional achievement from Columbia College, and his induction into the Cable Television Hall of Fame. “They are nice indications that people out there think you made some sort of difference with your life,” Rosencrans says. “I am certainly grateful.” Jonathan Lemire ’01 is a frequent contributor to Columbia College Today and a staff writer for The New York Daily News.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||