Swimmer Katie Meili ’13 sets her sights on Rio’s Summer Olympics.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Swimmer Katie Meili ’13 sets her sights on Rio’s Summer Olympics.

Photographs By Corey Fox

Headed into the star-studded Duel in the Pool meet in December, Katie Meili ’13 was nervous, she told her coach David Marsh. She was fatigued from months of hard training, her limbs felt leaden and her muscles ached — not atypical complaints for an elite swimmer, but not a reassuring sensation going into a competitive meet. The American squad was gunning for its seventh consecutive victory at the biennial, trans-continental matchup, but as the meet unfolded, the European swimmers were keeping things close.

It was time for a pep talk. “I told Katie, ‘Here’s the truth of the matter: You’re training better right now than at any time last year,’” Marsh recalls. “‘Last year, at your best, you weren’t able to do what you’re doing right now.’”

As it turns out, no one at their best could do what a tired Meili was about to do. Pushing exhaustion aside, she emerged from the meet with an American record in the 100-meter breaststroke, her prime event, and gave her world-record-setting 400m medley relay team the edge it needed to pull out the win.

Riding the wave of a breakthrough season that included a gold medal at the Pan Am Games, Meili cemented her standing as the United States’ top sprint breaststroke prospect at the Duel. Her standout summer had not been a fluke: Over the course of several months, Meili shot from a middle-of-the-pack, dark-horse candidate for the U.S. national team to a legitimate medal contender at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics, coming up in August.

But talking about medals is premature; first, she needs to make the U.S. Olympic team, a task said by some to be even harder than medaling at the Olympics. This summer, America’s most competitive swim meet will light up (perhaps literally — in 2012, it featured flames spurting from the deck) Omaha’s CenturyLink Center from June 26 to July 3, drawing Meili and more than 1,000 other swimmers, most of whom grew up dreaming of reaching that elite level.

Meili spent her childhood in Colleyville, a suburb of Fort Worth, Texas, where, at 8, she met her initial summer forays into competitive swimming with disinterest and consternation. Ribbons proved to be the key incentivizer, and, eye on the prize, Meili went from a non-finisher to third place in a single meet, and subsequently from summer league to a year-round club team.

She was a serious student and a dedicated swimmer throughout high school. It was at the 2008 Junior Nationals, the top annual meet for swimmers under 18, that she was first scouted by Diana Caskey, Columbia’s longtime head coach for women’s swimming. “She was good, but she wasn’t, ‘Oh my gosh, she’s going to blow the doors off at championships,’” Caskey says. “It was more like, ‘She’s a great match [for Columbia] — her personality, the commitment of her parents, all those things that go into recruiting the Ivy athlete.” Though obviously talented, Meili’s focus didn’t really sharpen until halfway through her collegiate career. “She lived the college life for her freshman and sophomore years, and then she decided she wanted to turn up the heat and really make her mark [in swimming],” Caskey says. “College is tough. There’s so much to do and so many different ways to spend your time. It takes a lot of sacrifice to fully invest in yourself and your sport.”

From there, Meili’s swimming career took off as she posted school and Ivy League records, won “Swimmer of the Meet” honors at the 2013 Ivy championships and the Connie S. Maniatty Outstanding Senior Student-Athlete Award, awarded to the top graduating male and female Columbia athletes. She capped her college career on an even larger stage, snagging a bronze medal and All-American honors in the 100-yard breaststroke at the 2013 Division I NCAA Swimming Championships, a feat almost unheard of for an Ivy Leaguer, not to mention a swimmer who didn’t even make NCAAs until the year prior.

It’s impossible to touch on Meili’s success without mentioning Cristina Teuscher ’00, a larger-than-life presence in the annals of Columbia athletics and especially Columbia swimming. Teuscher — the last female Olympian swimmer from the Ivies — entered Columbia having already won gold at the Olympics and exited a multi-time NCAA champ and Honda Sports Award winner, with more pool, school, Ivy and NCAA records to her name than is reasonable to count.

“There is no one in the league like her, past or present, and there will most likely be no one like her in the near future,” a Spectator sports reporter wrote the November following Teuscher’s graduation, and indeed, her name dominated the Uris Pool record board for years after her departure. But less than a decade later came Meili, who started threatening the records that were supposed to stand for time immemorial, before making waves at NCAAs.

The podium finish at NCAAs would have made a storybook ending to an unlikely career, but Meili didn’t stop there. Instead, she moved on to Act II. Taking a gamble, she plunged into the world of professional swimming — hardly a secure career move for anyone not named Michael Phelps or Ryan Lochte — and moved to Charlotte, N.C., to join Marsh’s invitation-only swimming group Swim- MAC Carolina Team Elite (which includes Lochte, an 11-time Olympic medalist).

“It’s a serious longshot,” says Caskey of the leap of faith it takes to pursue a pro career. “There are a lot of people gunning for that type of success, and it’s very challenging, very difficult, on many levels.”

“When I was coming to the end of my [college] career,” says Meili, “I had had so much fun that I wasn’t really ready to give it up.” Given the go-ahead to join Marsh’s post-grad group and a little logistical luck, “It was like, ‘OK, this is too perfect, I think the universe is trying to tell me something.’”

The podium finish at NCAAs would have made a storybook ending to an unlikely career, but Meili didn’t stop there.

Marsh’s team set her up with a host family that allowed her to live with them rent-free, and through family connections she found a job flexible enough to accommodate her practice schedule.

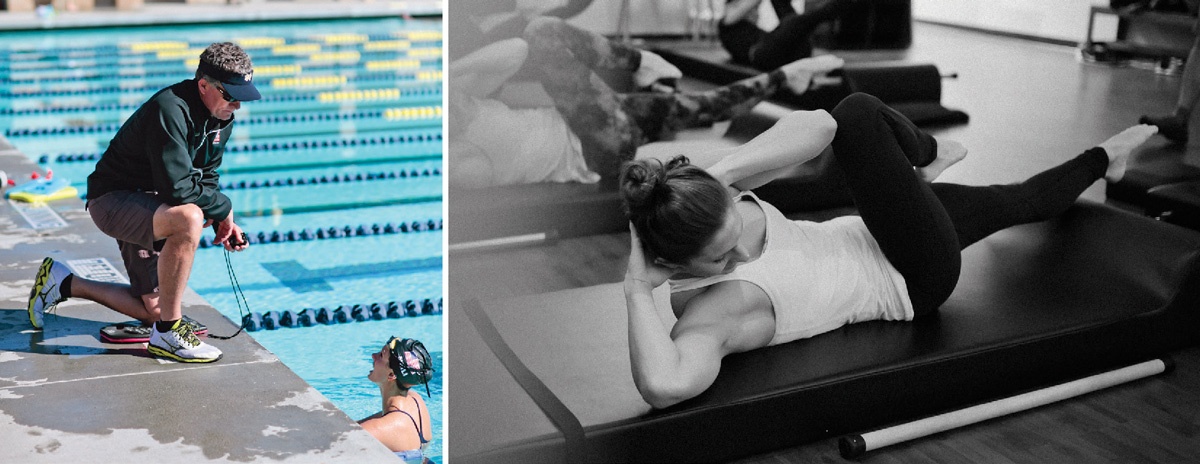

When she finally arrived at SwimMAC Carolina’s loaded Team Elite — Marsh (above left, with Meili) won’t even take on a swimmer unless he believes he or she has a serious shot at an Olympic Trials final, and most are aiming for an Olympic medal — Meili had the unusual experience of feeling, for once, like a fish out of water.

“I thought, ‘Oh, I don’t really belong here, I’m not the best, I’ve never made the Olympics and I’ve never made a national team.’ I was walking around with this ‘I don’t belong’ attitude,” Meili says.

And, at least at the beginning, Marsh agrees that her talent didn’t set her apart. “Swimming-wise, I would say she was very average, so she didn’t stand out at all in the water,” he says. “She just worked hard every day and came in with a smile.”

The workload that goes into being a part of Marsh’s elite group is daunting. As a professional swimmer, Meili can spend up to six hours a day in the pool and weight room during double-practice sessions. Marsh, who developed dozens of Olympians while coaching at Auburn, is famous for his demanding workouts, which can involve anything from Pilates to rope-climbing and always involve a “no pain, no gain” mindset. Because of Meili’s laser focus and dedication, Marsh says he more frequently has to warn her to back off from training too hard than anything else.

“If I hadn’t have gone to Columbia, I wouldn’t be the person I am today and I don’t think I’d still be swimming.”

As promised in Rocky montages, the grueling work began to pay off, and Meili started gaining momentum, both in the pool and out. Her rising profile brought in endorsement deals, which enabled her to leave her day job at Direct ChassisLink (the firm continues to support her through sponsorship). She also was able to get a place of her own, which she shares with teammate Cammile Adams and their one-eyed cat, Boo.

The international meet rosters for this summer were based on the results of the 2014 U.S. National Championships, where Meili finished fifth in the 100m breaststroke — not enough for an invitation to the FINA World Championships, but enough to earn her a bid to the Pan- American Games, to be held the week prior in Toronto.

There, Meili won the 100m breaststroke in an attention- grabbing 1:05.64, bettering her personal best by nearly a second and breaking the meet record by two seconds. It was the third-fastest time in the world last season and would have been enough to win the gold at the World Championships the next week.

“It made me feel like what I was doing was justifiable and it wasn’t a delusion — it was a reality,” she says. “That was more of a relief than anything, because I thought, OK, I’m here, I can do this, and now I can really focus on getting better instead of focusing on convincing other people I belong.”

According to her friends, though, she’s still trying to grow into the role of world-class swimmer rather than Ivy-educated underdog.

“Katie has had to remind herself that she has done the work, and she is as good as she is,” says Adams, a 2012 Olympian. “Sometimes I have to say, ‘Katie, come on, you’re one of the fastest swimmers in the world — how cool is that?’”

Even now, having made a national team, Meili recognizes that she sticks out because of her unusual pedigree, but says she’s proud to represent Columbia. “I love telling people if I hadn’t have gone [to Columbia], I wouldn’t be the person I am today and I don’t think I’d still be swimming.”

With arduous daily workouts, Meili is the first to admit that following her dream isn’t easy. And it’s not as if she’s never thought about what would have happened if she hadn’t traded her cap and gown for a swim cap and training suit.

“Of course, I can imagine it,” Meili says. “I miss the people I went to school with, and I really miss New York.

“This is hard. I get to do incredible things, but it is very stressful, physically and mentally. I am really happy I did what I did, but I also do miss the life that I probably would have had.”

In the end, the sacrifices Meili has made will hinge on a narrow window at the Olympic Trials — about a minute, give or take, the time it takes to swim two laps in a 50m pool. While Meili intends to swim a full program, the 100m breaststroke is her signature event and her best chance at a trip to the Olympics. Aside from that, an impressive performance at the Austin Grand Prix in January put her in contention for a 200m breaststroke berth, and she’ll also be vying for one of the 400m freestyle relay slots that are awarded to the top six finishers in the individual 100m free.

“You only have one certain day, and you either win or you don’t,” Adams says. “She has to show up on race day.”

As a make-or-break moment, the Olympic Trials are a perfect stage for upstarts, and it wouldn’t be the high-stakes meet it is without some upsets. The wise know to temper their expectations, especially in a sport where the difference between medalists and losers often lies in fractions of seconds. “It’s possible I’ll have the best swim of my life and still not make the Olympic team,” Meili says matter-of-factly.

What’s more, there’s always the unforeseen. At the 2012 Trials, Meili broke her hand while warming up and lost her chance to qualify for the London Olympics.

Regardless of the outcome in Omaha, Meili plans to continue competing on the professional circuit through the 2017 season, after which she’ll decide whether to keep swimming or go back to school — right now, she’s thinking about earning a law degree.

In any case, she has no regrets about her choice.

“Most swimmers will tell you that the Olympics are the ultimate goal,” she says. “But I think it’s important to find ways to keep it valuable, even if you don’t consider the Olympics … Every day I want to feel like I’m really invested in and learning as much from the process, and getting as much happiness out of every single day as I would making the Olympic team.

“If it weren’t to happen, of course I would be disappointed, but I wouldn’t leave feeling like I had just wasted two years of my life. I really think I’m at the point where I’m never going to say that. This journey has been incredible.”

Charlotte Murtishaw BC’15 is a Student Conservation Association intern in Nebraska, where she is a volunteer coordinator for the National Park Service.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu