The singer who shaped a generation looks back on his life before and after Paul Simon.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

The singer who shaped a generation looks back on his life before and after Paul Simon.

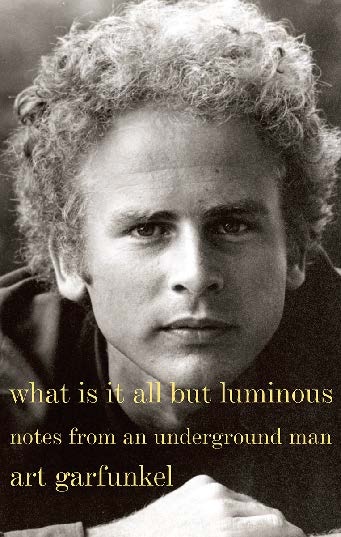

It’s this sort of ethereal, almost angelic mindset — combined with his halo of blond curls, and the soaring glory of his countertenor voice — that led Rolling Stone to dub Garfunkel “the choirboy of pop music.” But then Garfunkel has always been a bit of an anomaly. “I think of myself as a little bit of a misfit in today’s times,” he told Forbes. “Modern America looks goofy to me. Maybe I’m different. Maybe I’m the goofy one.” This appealingly thoughtful outsider’s stance infuses Luminous, a highly personal look back at a life lived through music.

With Paul Simon, his childhood friend from Queens, Garfunkel achieved early musical stardom, hitting the national charts in 1957 as Tom and Jerry, with the song “Hey Schoolgirl.” After changing their name to Simon & Garfunkel, the duo went on to create generation defining songs, including “The Sound of Silence,” “Homeward Bound” and “Mrs. Robinson,” before splitting in 1970.

As Garfunkel sees it, his existence (so far) falls into two acts: Before and after the final Simon & Garfunkel album, Bridge Over Troubled Water. Garfunkel’s years at Columbia — he enrolled at the Architecture School before switching to the College to major in art history — formed a vital and sustaining part of that first act. After that first ’50s hit, the friends’ music failed to sell, and each went back to school (Simon graduated from Queens College). Garfunkel’s middle-class upbringing had shaped him to seek a conventional life: “I was the kid who was going to go to college and find some way to make a decent living,” he says.

“Sweet memories” sums up the time he spent on Morningside Heights, including singing a cappella with the Kingsmen and reading textbooks to his roommate Sandy Greenberg ’62, BUS’67, who was stricken with glaucoma. Perhaps most extraordinary for Garfunkel was the ubiquity of books at Columbia, and the seriousness with which they were treated. “People would sit around at dinner and talk about books, and I thought that was just fabulous,” he says.

Garfunkel and Simon revived their act in 1964; Garfunkel remembers Simon bursting into his room with the lyrics of “The Sound of Silence.” Columbia has a bit part in their later musical history, as well — the big sound of their hit “The Boxer” was partly recorded in an illicit late-night session within the high stone walls of St. Paul’s Chapel. After smuggling in equipment, the pair “stayed there all night, singing all 16 ‘li-la-lis,’” Garfunkel recalls.

Since those early days, Garfunkel has recorded his own songs (“All I Know”) and successful solo albums (Angel Clare, Breakaway), and has acted in such films as Catch-22 and Carnal Knowledge. The following excerpt from Chapter One of Luminous describes his childhood infatuation with music and the early years of his tight-knit friendship with Simon.

— Rose Kernochan BC’82

Singing is a tickle in the back of the throat, a flutter of the abdomen, the vocal cords, called vibrato. It’s sent from God through the heart, and it is un-analyzable. Some people can just do it. They listen to the radio and begin to emulate. At five or six, I was doing the inspirational songs that I heard, like“You’ll Never Walk Alone.” I heard my parents singing “Bye Bye Blackbird” in the living room — in two-part harmony. That I could do it too was a delight that took me to places where echo put tails on my notes — lovely extensions of sound. I fell in love with the magnifying effect of tiled rooms, hallways, and stairwells. When no one was listening, I sought to make beautiful vowel sounds for my own ears’ sake. It was my private joy. Walking in rhythm over sidewalk cracks, I sang my tune.Th en did it again in the next higher key. I was on my way to first grade.

Write the poem out loud

Authorize the heart

Burn the Bridge and

Be the work of art

My singing was a serious gift that I respected all through my childhood, my life. I was skinny, a lefty, a Scorpio. My father called me “Whitey Skeeziks” but I identi ed with the “A” of Arthur. It was steeple-shaped, upward aspiring, hands in prayer. I loved my white satin collar when I sang in the temple. I was the angel singer and I felt “touched.”

I went for the songs that had the goose bumps. “If I Loved You,” from Carousel, did it for me, Nat Cole’s wonderfully different “Nature Boy.” And I went to singers I just knew could sing: How easy was Bing Crosby’s “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas.” How brunette smooth was Jo Stafford’s “Fly the ocean in a silver plane.” How open-throated Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me.” How extraordinary “It’s Not for Me to Say” (Johnny Mathis). I saw Little Richard at the Brooklyn Paramount in ’55 stand on the piano in a purple cape. He ripped through “Long Tall Sally” and took the night. I fell for the great groove records. “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” had it (Jerry Lee Lewis). So did “Don’t Ya Just Know It” (Huey “Piano” Smith). Frankie Ford’s “Won’t you let me take you on a Sea Cruise” was as good as it got for me.

On Saturday mornings, in 1953, in Keds sneakers, white on white, I took my basketball to P.S. 165. We played half-court ball, three on three. Or else I listened to Martin Block’s Make Believe Ballroom on the radio. I loved to chart the top thirty songs. It was the numbers that got me. I kept meticulous lists — when a new singer like Tony Bennett came onto the charts with “Rags to Riches,” I watched the record jump from, say, #23 to #14 in a week. The mathematics of the jumps went to my sense of fun. I was commercially aware through the Hit Parade, as well as involved in the music. Johnnie Ray’s “Cry,” the Crewcuts’ “Sh-Boom,” Roy Hamilton ballads, “Unchained Melody” reached me. Soon the Everly Brothers would take me for The Big Ride.

As I entered Parsons Junior High where the tough kids were, Paul Simon became my one and only friend. We saw each other’s uniqueness. We smoked our first cigarettes. We had retreated from all other kids. And we laughed. I opened my school desk one day in 1954 and saw a note from Ira Green to a friend: “Listen to the radio tonight, I have a dedication to you.” I became aware that Alan Freed had taken this subversive music from Cleveland to New York City. He read dedications from teenage lovers before playing “Earth Angel,” “Sincerely.” When he played Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally,” he left the studio mic open enough to hear him pounding a stack of telephone books to the backbeat. is was no Martin Block.

Maybe I was in the land of payola, of “back alley enterprise” and pill-head disc jockeying, but what I felt was that Alan Freed loved us kids to dance, romance, and fall in love, and the music would send us. It sent me for life. It was rhythm and blues. It was black. It was from New Orleans, Chicago, Philadelphia. It was dirty music (read “sexual”). One night Alan Freed called it “rock ‘n’ roll.” Hip was born for me. Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis. Bobby Freeman asked, “Do you wanna dance, squeeze and hug me all through the night?” and you knew she did.

I was captured. So was Paul. We followed WINS radio. Paul bought a guitar. We used my father’s wire recorder, then Paul’s Webcor tape machine. Holding rehearsals in our basements, we were little perfectionists. We put sound on sound (stacking two layers of our singing). With the courage to listen and cringe about how not right it was yet, we began to record.

We were guitar-based little rockers. Paul had the guitar. I wrote streamlined harmonies whose intervals were thirds, as I learned it from the Andrews Sisters to Don and Phil and floated it over Paul’s chugging hammering-on guitar technique. It was bluesy, it was rockabilly, it was rock ’n’ roll. We took “woo - bop - a - loo - chi - ba ” from Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-A-Lula.” We stole Buddy Holly’s country flavor (“Oh Boy”), the Everlys’ harmony (“Wake Up Little Susie”). Paul took Elvis’s everything (“Mystery Train”). As he drove the rhythm, I brought us into a vocal blend. We were the closest of chums, making out with our girls across the basement floor. We showed each other our versions of masturbation (mine used a hand). “The Girl for Me” was the first song we wrote — innocent, a pathetic “Earth Angel.” In junior high we added Stu Kutcher and Angel and Ida Pellagrini.

All the while, I did a lot of homework, the shy kid’s retreat. My geometry page was a model of perfection. Anything worth doing is worth doing extraordinarily well — why not best in the world?

My mother could prettify anything. If Darth Vader appeared in my bedroom, live at 3 a.m., and I was nine — my mother would say to him, “Dorothy, put down the mask, you’re no Lancelot, then come down for mah-jongg and crumb cake.” And the girls called him “Dot.”

At twelve I was in my seventh year of being a singer when Paul and I got together. We became rehearsal freaks of fine exactitude. We did our version of doo-wop, copying Dion and the Belmonts. We wrote “A Guy Named Joe.” We fused rock ’n’ roll with country (rockabilly), the way Buddy Holly did. But it all took flight when Don and Phil Everly started having hits in 1956. We fell out over their sound. Every syllable of every word of every line had a shine, a great Kentucky inflection, charisma in the diction. From moment to moment they worked the mic with star quality. The Everlys were our models. Paul and I wrote our songs together and practiced getting a tooled, very detailed accuracy in our harmony. We came together, with mouths, a foot apart, under a dome of very fine listening, and fashioned a sonic entity of its own.

Excerpted from: WHAT IS IT ALL BUT LUMINOUS: Notes from an Underground Man by Art Garfunkel. Copyright © 2017 by Art Garfunkel. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu