Informed by history, Nishant Batsha ’10’s latest novel combines romance and revolution

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Informed by history, Nishant Batsha ’10’s latest novel combines romance and revolution

LIBBY MARCH

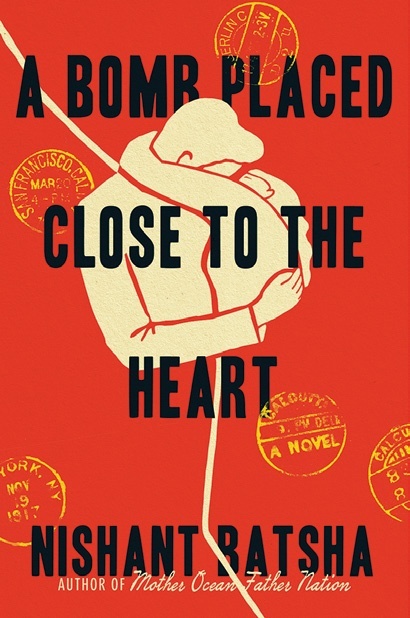

He decided to stick with both pursuits, and while working toward his Ph.D., he began to write historically informed fiction. Amidst his research Batsha chanced upon stories about a small band of South Asian revolutionaries who lived in California in the early 20th century and were starting a movement to overthrow the British empire. Batsha was intrigued enough to look for a narrative hook and learned of the passionate real-life romance between an Indian nationalist and an American graduate student. An adaptation of their love story, set in 1917 at Stanford and in New York City, is the backdrop of his second novel, A Bomb Placed Close to the Heart (Ecco, $27.99).

The characters Indra Mukherjee and Cora Trent are based on Manabendra Nath (“M.N.”) Roy, an activist and political theorist who founded Communist parties in Mexico and India, and his wife, feminist and idealist Evelyn Trent. Mukherjee and Trent meet in Palo Alto and sparks fly; their love story deepens as they attend protests alongside anticolonial dissidents and socialize with bohemian thinkers in the Bay Area. As the United States is drawn into WWI, the hastily married couple is forced to flee to NYC to avoid the attention of British and American authorities.

Batsha set A Bomb Placed Close to the Heart near his hometown in the San Francisco Bay Area as a way to explore the area where he grew up. “When you think about the Bay Area, most people think about innovation and technology, but this is a very different Palo Alto in the novel,” he says.

Batsha went east for the first time in 2006 to attend the College, and says he fell into studying history by chance. He became suddenly and seriously ill during the spring of his first year, which “broke any momentum I had had,” he says. After taking a semester off to recover, he wanted to try different courses in order to decide what he might major in. “Latin American History I,” taught by associate professor Caterina Luigia Pizzigoni, set him on his path. He went to Oxford as the 2010 recipient of The Jarvis and Constance Doctorow Fellowship, and completed a master’s there before returning to Columbia for his Ph.D. His thesis about labor migration formed the basis of his first novel, Mother Ocean Father Nation, which was a finalist for a Lamda Literary Award and was named one of the Best Books of 2022 by NPR.

Batsha doesn’t like having down time when it comes to his writing, and began work on A Bomb Placed Close to the Heart just weeks after wrapping Mother Ocean in late 2021. “I found the story of M.N. and Evelyn, and I knew what I wanted to do with it,” he says. “The characters of Indra and Cora came out of my own surmising of what they would look like together and what emotions they would navigate.”

In the chapter excerpted here, narrated by Cora, the pair travel from Palo Alto to Berkeley and get to know each other better. As Indra talks about his life in India under British rule and his desire to take direct action that might crush the empire, Cora begins to wonder if Stanford might be too pastoral for her.

Batsha himself enjoys “a charmed writerly life” in Buffalo, N.Y., with his wife, a professor of art conservation (“We call her job ‘the puppy dog’ because whenever it comes up, people fawn over it,” he says with a laugh) and their two children. He spends half his time as a ghostwriter for CEOs, the other on his next book, about a disillusioned Civil War veteran who joins a Shaker community in rural Maine and forms a meaningful relationship with a young orphan.

“I really want to take my time with this one,” Batsha says. “Writing a novel feels like this antiquated art that really doesn’t jive with how the world works anymore — but sometimes you’ve got to luxuriate in that.”

— Jill C. Shomer

The conversation with Indra moved as easily as the steam and fire of all the forms of transport that took them to their destination. They told each other stories of their youth — she enjoyed recounting to him how she grew up in the hardscrabble mines. He couldn’t believe that she had lived for so many young years in such desolate places, and he had such great pity for the loss of her mother. He seemed sadder about it than she ever felt, but she soon learned that his own mother had passed away a year or so ago, and he was speaking of his grief through her loss.

He spoke of his upbringing in India, particularly his brief wanderings as an ascetic. Indra’s grandfather had been the village priest, which meant that there was some sort of manhood ceremony when he was ten years old where he had to become a peripatetic mendicant. Temple to temple, he wandered, gurus waiting to tell him the same tenets over and over: see the world that passes by for what it is, a story, an illusion.

Reading gave way to action, she learned. Indra gave up his religion when he was eighteen and the British announced their plan to partition Bengal in two, to take the power of that region and neatly divide it upon an invisible border. It was an outrage to divide a place upon a simple religious line, one Hindu, one Muslim — he joined the street marches to protest, and in him grew a desire for direct action, a fist that could rise above a simple collection of voices upon the street to grab at and crush the heart of empire.

“These men in Berkeley, they feel the same thing,” he told her. “They’ve made a political party called the Ghadar.”

“What does that mean?” Cora asked. She said the word internally: Gha-dar. It sounded all wrong, nothing like how he said it.

“It means the revolution. They’re the Party of Revolution. They organized about five years ago. Their members move between here and the Punjab, mainly. They want the same thing I do: total liberation of India from foreign rule.”

“Are there many Indians in the Ghadar in California?”

“There were more a few years ago. Now it seems to be mainly students and writers. They’ve made inroads with the Sikh Punjabis working the farms in the state.”

“I didn’t know there were Indians farming in the Central Valley,” she said, curious about a history and people that seemed hidden from her. “Why are they here?”

Indra shrugged. “Why is anyone anywhere? One man has an idea and takes a boat. If he’s able to find some sliver of a good life, he writes home. His cousin, his uncle, his nephew, and maybe even his best friend’s brother’s son’s brother arrive soon enough.”

Cora chuckled. “Is that why there are men studying at Berkeley as well?”

“For the most part. One man found he could come here and learn without having to bow down to the British at Oxford or Cambridge. The men reading for degrees at Stanford and Berkeley are the same. They don’t want to beg their lords and masters for an education.”

This seemed, to Cora, entirely different from the countless editorials and articles at the Union about the Asian menace creeping across the state, a tide of workers seeking to undercut the wages of good white men.

The two finally arrived in Berkeley near two in the afternoon. As they walked from the edge of the Cal campus to their destination, Cora wondered why she had chosen to attend Stanford over Cal, as the former seemed to be a pastoral destination, cloistered off from greater society. This was a place where city and school moved together, filled with a life that emanated from the Campanile chiming in the distance. As they walked down Telegraph Avenue, she overheard conversations in French, in German, and outside a teahouse, a man slamming down his hand on a table, exclaiming, “Cubism will not survive the war in Europe!” This wonder was not limited to her attention: she saw how Indra too let his eyes wander this way and that with the look of a traveler newly arrived in a strange land, a moving and unfocused stare that confessed there was too much novelty to behold in a single moment.

From A Bomb Placed Close to the Heart by Nishant Batsha. Copyright © 2025 by Nishant Batsha. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu