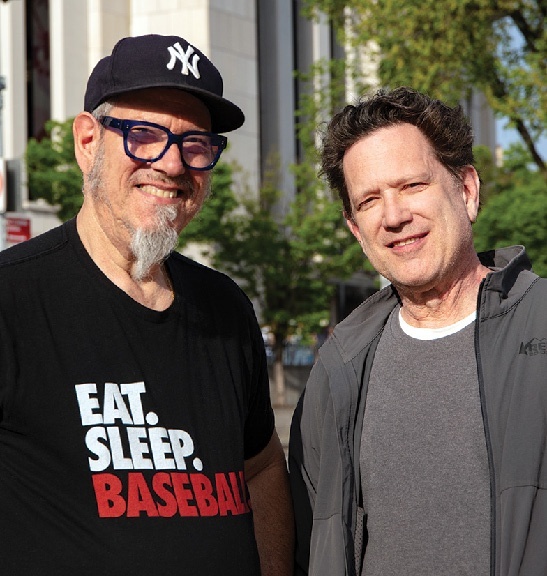

Michael Hickins ’83 and Michael Granville ’83 cemented their long friendship while rooting for the home team.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Michael Hickins ’83 and Michael Granville ’83 cemented their long friendship while rooting for the home team.

Michael Hickins ’83 (left) and Michael Granville ’83

JÖRG MEYER

These days, a different set of M&M Boys have made the stadium their second home, but instead of swatting home runs, Michael Hickins ’83, SOA’86 and Michael Granville ’83, GSAPP’92 swap stories — about their careers, their kids, their time on Morningside Heights — in Section 227, Row 7, Seats 15 and 16, of the park’s upper deck. It would take a colossal Aaron Judge foul ball to reach them, but distance doesn’t matter to the two Michaels. Closeness does. And baseball — Yankee baseball — is the magnet that keeps pulling them together, from spring to fall, cementing a friendship kindled by a chance meeting during Orientation 46 years ago.

“Michael is my closest friend; he’s irreplaceable,” Hickins says. “If we didn’t have [Yankee games], it would be really hard to get together, and I would miss him a lot.”

Since 1999, when Mariano Rivero was still mowing down batters and Derek Jeter was still slapping clutch hits the opposite way, the modern-day M&M Boys have shared a partial Yankee season-ticket plan. The package gets them 16 games (mostly Friday nights), access to postseason tickets and, best of all, a chance to keep their friendship sharp while witnessing baseball history.

They leaped and high-fived and belted “New York, New York” together after escaping Game 1 of the 2000 World Series against the Mets with a gripping 12-inning win. They “Holy cow!”-ed together when Scott Brosius tied Arizona with a two-out, two- run, ninth-inning homer, giving the Bombers life in Game 5 of the 2001 World Series. And they winced and ugh-ed together watching Pedro Martinez of the archrival Red Sox masterfully strike out 17 Yanks on a September night in 1999. Along the way, they’ve sung “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and “YMCA” more times than two off-key 64-year-olds should be allowed.

“Michael’s voice is as bad as mine,” Granville confides, trying to hold back a smile. “The only reason I sing is because he does.”

The Mikes from Queens were 18-year-olds when they met in John Jay Hall on the first night of Orientation in 1979. (Yes, they’re from Queens, and not Met fans. More on that to come.) A day or so later, outside Chock full o’Nuts on Broadway, they bonded over poetry and prose. Their own. “I had a folder of my high school fiction, a lot of Beat generation mimicry. Garbage, really,” recalls Granville, who today is a limited partner in a Manhattan architecture firm. “Mike was writing a lot of poetry at the time. We were standing on the corner basically handing each other our writing.”

For much of their College years, classics, not curveballs, connected them. The two English and comparative literature majors shared several classes, including “Eliot, Joyce, Pound,” which led to meet-ups at Symphony Space for readings of Ulysses. But after graduation, in those dispirited Yankee years of the mid-1980s, the pair headed to 161st Street and River Avenue for a different kind of drama. Hickins initiated the trips. Even though he grew up along the 7 line, a few stops from Shea Stadium, he’d become a Yankee fan by osmosis.

“Michael is my closest friend; if we didn’t have [Yankee games], it would be really hard to get together, and I would miss him a lot.”

“My parents listened to WQXR, the classical music station,” Hickins says. “And every hour there was a news report with a very serious voice talking about world leaders like Henry Kissinger, and every once in a while he would evoke the name of Mickey Mantle with the same reverence. It dawned on me that Mickey Mantle was a real person who played baseball for the New York Yankees.” Once The Mick retired, Hickins latched onto the likes of Celerino Sanchez, Horace Clarke and, for sure, Ron Blomberg. “Oh, I loved him — I mean, a Jewish ballplayer!” Hickins gushes. “But he was always hurt.”

In the bleachers, over sausages and bad beer, Hickins — who nearly made the Columbia baseball team as a walk-on pitcher — would lead a tutoring session, telling his buddy when the Yanks needed to hit and run or get the bullpen up. Then, like now, Granville says, going to the stadium with Hickins was a “deep dive” into the game, so much so he converted from Met to Yankee fan. As Granville puts it, “The game is so engaging when you have someone with that knowledge.”

The friendship withstood a nearly 12-year separation. Hickins moved to France in 1985, living first in Paris and then later in the western port city of La Rochelle, where he owned a restaurant and, on the side, coached a French baseball team. A fine life, with one major drawback: When the Yankees finally returned to the World Series, in 1996, Hickins had a hard time keeping up with their games from across the Atlantic. The French broadcaster airing the series often killed the feed well before the seventh-inning stretch. “I was pulling my hair out with anger,” Hickins recalls. His solution: He’d call Granville in New York, begging his friend to be his per- sonal John Sterling. “I was kind of annoyed,” Granville now admits, “so maybe it wasn’t the most gracious play-by-play he ever heard.”

The long-distance calls did enhance Granville’s ardor for the game, and when his friend returned to the metropolitan area, he suggested they team up for season tickets. “We got the cheapest 16-game plan you could get,” Granville says, “and still have the right to get postseason tickets.” A Friday night ritual was born.

Most nights they get to the stadium 45 minutes before the first pitch, Granville via the D train from Manhattan, Hickins on Metro-North from his home in northern Westchester County, where he works remotely in communications for Oracle Corp. They get a poke bowl. (“This is a recent-year thing,” says Granville. “You got to start eating a little more healthy.”) In their seats the talk is mostly strategic, the ebullient Hickins dissecting outfield alignments or predicting which pitch should come. But through the years they’ve shared the ups and downs of, well, life.

Granville has lamented about a work project gone wrong; Hickins has confided about a romance or two that soured. But it was also in the upper deck where the friends, first united by a shared interest in storytelling, talked about Hickins’ parents and their unlikely escape from the Holocaust. The conversations helped distill what became Hickins’ most recent of five authored books, The Silk Factory: Finding Threads of My Family’s True Holocaust Story. “[Michael has] written a lot of brilliant fiction, gobsmackingly intense work,” Granville says, “but this was something else. The humanity in this book ... it was really powerful. I’ve never been prouder of anybody than I was of Mike writing that book.”

They usually wait for the last out, for Sinatra to start crooning. Steadfastness often pays off; witness a Friday night in 2002. With the centerfield clock inching toward 1 a.m. and only a smattering of drenched Yankee fans remaining in the park after nearly six hours, the Yankees’ Jason Giambi crushed a grand slam, in the 14th inning, to beat the Minnesota Twins, 13–12. The only blemish? Hickins had no one to high-five. His buddy had gone home a few innings earlier. “To my shame,” Granville admits, “I wasn’t there for the walk-off.”

It’s a memory, like so many others, that fuels a friendship, keeping two pals coming back to the Bronx after all these years.

Charles Butler ’85, JRN’99 is a journalism professor at the University of Oregon. He is researching a book on Lou Little.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu