Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

A Street Burns in Brooklyn

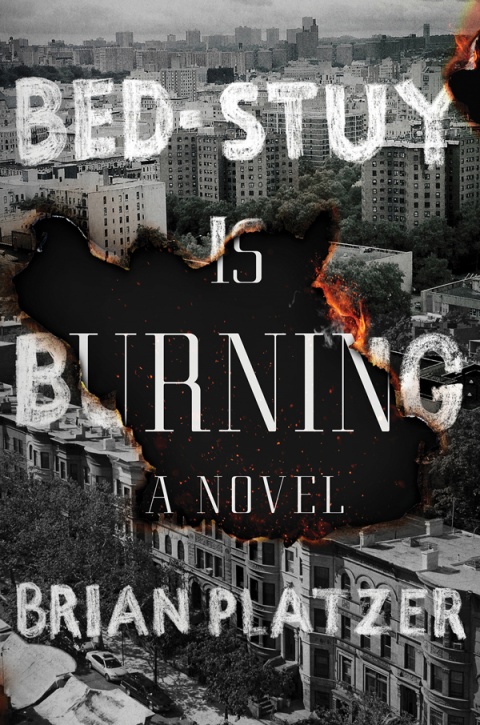

It would be a bold choice to unpack topics like gentrification, white privilege and police brutality in your first novel at any time; at this particular moment, it’s downright audacious. But Brian Platzer ’04 went there, and his debut, Bed-Stuy is Burning (Atria Books, $26), has drawn praise for walking a fine line. Kirkus called it “eminently readable” while The Wall Street Journal noted his deft navigation of clashing points of view. Author Alice McDermott even declared the book “a Bonfire of the Vanities for Millennials.”

Lauren Silberman

Bed-Stuy is Burning tells the story of the escalating tensions that follow the fatal police shooting of an unarmed 12-year-old in the eponymous Brooklyn neighborhood, in the voices of a mixed group of residents: Aaron and Amelia, brownstone owners new to the block; their tenant, Daniel; their nanny, Antoinette; a neighbor, single father Jupiter; and rebellious local teenager Sara. Though it’s a work of fiction, actual streets, subway stops and restaurants are named; writer and educator Ta-Nehisi Coates is referenced; and former NYPD commissioner William Bratton even narrates a few chapters.

The real-life inclusions came naturally to Platzer, who lives in the neighborhood he’s writing about and was motivated by what he saw happening around him. “Around 2010 I began to notice black teenagers, with increasing frequency, being handcuffed by police on the subway platform near my home,” he says. “I couldn’t shake the thought that something was going to explode out of these fraught interactions.” Though he is outwardly most like his character Aaron, a lapsed rabbi, Platzer spent two years doing extensive research to ensure he could properly speak in other voices. The background work included interviews with a diverse group of neighbors, police, local high school kids and teachers.

Still, the book has raised a few eyebrows, and Platzer has had to respond to pushback that he isn’t the right person to tell this story. “I get that people don’t want a white person to tell the story of groups that white people have oppressed,” he says. “I respect that argument but I disagree — to say that there is a certain story that only a certain type of person is qualified to tell, you’re creating divides. That someone is so much the ‘other’ that I can’t invent or imagine their thoughts — it strips the humanity away from them. That would mean literature can’t be an exercise in empathy, that you’re forced just to focus on your own experience.”

Platzer, a native New Yorker, deferred Columbia for a year after high school and spent six months teaching English in Thailand and six months working at a fashion magazine in Paris. He found that city “devastatingly lonely”; to pass the time, he wrote.

At the College, he double-majored in French lit and English lit and continued to write. “The intellectual excitement was unbelievable,” he says. “It was a wonderful time. I’ve tried to prolong that life as a creative person.” He read constantly; he says he particularly enjoyed contemporary American fiction. “A lot of people read books to escape and experience other worlds,” he says, “but I like novels that describe people and worlds I know, and that get deep and honest into people’s minds. I fell in love with James Baldwin, Dave Eggers, Denis Johnson, Philip Roth.”

Platzer found focus in a personal essay class taught by Leslie Sharpe GSAS’73: “I wrote from the standpoint of a distorted version of me, and it opened my eyes to the way I wanted to be writing. I am interested in fictional characters that are slightly more extreme in their decision making.” To that end, some of his Bed-Stuy characters could be considered unlikeable; or as he says, “not the type of likeable that people who are accustomed to reading first novels written by Brooklynites are anticipating…. But I wanted everyone to be recognizably selfish. The ugly hidden thoughts interest me more.”

Platzer met his wife, Alexandra Hardiman ’04, in his first year at the College, when they were both living in John Jay. They have two children, ages 2 and 4.

Platzer teaches part time, at the Grace Church School in Manhattan. His students are middle schoolers, ages 12–14; he says he especially enjoys teaching that age group. “They are the most excited to be taught,” he says. “They want to be taken seriously and I present them with serious material. Right now I’m teaching them Night by Elie Wiesel.”

He is also at work on a new novel; like Bed-Stuy is Burning, this tale takes place close to home — in his own body. In 2010, Platzer started experiencing constant dizziness; a year later he was diagnosed with vestibular migraines. Though his symptoms are mostly relieved with medication, he still struggles and can only write for short periods. The novel, to be published by Simon & Schuster, is told from the point of view of the wife of a man dealing with a debilitating neurological disorder.

When not writing or teaching, Platzer has been doing readings from Bed-Stuy in schools, bookstores and Jewish centers. “This whole thing has been a dream,” Platzer says. “I’ve been trying to create the architecture for this life for more than a decade.”

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu