Anxiety on campus is a national concern.

How are colleges supporting students’ emotional well-being?

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Anxiety on campus is a national concern.

How are colleges supporting students’ emotional well-being?

Cristen Scully Kromm, dean of undergraduate student life, has worked at Columbia for 18 years — first for Barnard, and now at the College. Since 2006 she has lived with her husband and family (two children and a rescue pup) in an apartment on the ninth floor of Wallach Hall. This means she also lives alongside approximately 240 under- and upperclassmen. Her presence has a certain warmth; she hosts dinners and study breaks and, every October, goes door to door with gift bags: tea for a cold day, a granola bar for a healthful snack.

On the day I visited Kromm’s office in Lerner Hall, in early September, she and Matthew Patashnick, assistant dean for student and family support, were recovering from the rigors of Orientation the prior week. Helping close to 1,100 first-years adjust to life at the College — along with helping families adjust to a life that doesn’t involve seeing their teenagers every day — is no mean feat. An abridged list of student activities includes meetings with residence hall and Orientation group leaders; group trips to Bed, Bath & Beyond; a campus resource fair; the first Lit Hum lecture; financial aid 101; lessons in library use; a cross-borough tour to Brooklyn; a Yankees-Red Sox game.

Of all the moving parts of Orientation, what the pair is most concerned with is perhaps the least visible: how students are faring in mindset and mood. The transition from high school to college can be fraught, rife with opportunity for expectations to clash with reality, and students can be sent reeling. “The message that we made clear throughout was ‘Ask for help when you need it,’” Kromm says. “It is OK to not have everything the way that you wanted it or thought it would be all of the time.”

The challenges extend into every corner of a new student’s experience. By and large they are living independently for the first time, responsible now for the instrumental decisions of daily life — when to wake up, what to eat, when to study, with whom to socialize. They might feel pressure to compete academically. They might feel pressure to load up on extracurriculars. They might feel lonely. Such massive change can be stressful to manage in and of itself; add to that the fact that 17- to 22-year-olds are developmentally at an age when mental health issues can start to manifest. “It’s this interesting moment in time when all of these things collide, and it’s right when they’re here and right when their parents are not,” Patashnick says.

That we are even having this conversation reflects a shift that’s occurred not just at the College, but also nationwide, as increasing numbers of college students grapple with mental health issues. And it’s not limited to first-years. The National College Health Assessment (NCHA) — the most comprehensive known survey on the health of college students — in spring 2017 found that nearly a quarter of all college students experienced anxiety that affected their academic performance; almost 16 percent cited depression. More than 10 percent had seriously considered suicide in the last 12 months, and 1.5 percent attempted it.

“One of the hardest things to teach, and that we strive to encourage, is that asking for help isn’t a sign of weakness — asking for help is a sign of strength.”

These statistics and others like them cap almost two decades of rising anxiety and depression rates in college students. The timing suggests a generational phenomenon — one that maps to the Millennials as they began arriving on campuses, in the late 1990s, and has continued with their successors, the so-called iGeneration. The possible reasons for their struggles are complex, involving the times these students were raised in, the way they were raised and changes in how we communicate. Colleges and universities, meanwhile, are being called on to understand and evolve to meet the needs of their newest charges.

At the College, expanding support for students and encouraging a culture of wellness has been a priority in recent years. “It feels like students are paying more attention to one another,” Kromm says. “With mental health [issues], they want to know how to help. That hasn’t always been a conversation here; the students can get very self-focused and driven; they have their small niche and their small community, and that’s who really matters. Now, for really the first time, it has seemed like people care beyond their own little bubbles.”

Still, the challenges are many. “There’s this stigma that a lot of our students feel — if you admit weakness, if you admit that something isn’t going right, then you’re different from your peers,” says Patashnick. “One of the hardest things to teach, and that we strive to encourage, is that asking for help isn’t a sign of weakness — asking for help is a sign of strength.”

The research field of campus mental health has largely emerged in the past 20 years. Prior to that, college counseling services were generally smaller operations, thinly staffed and with less funding. In 1964, psychiatrist Dana Farnsworth — director of Harvard University Health Services from 1954 to 1971 and an authority on students’ emotional problems — notably estimated that of the millions of college students in the country, one in 10 had emotional problems severe enough to warrant professional help. Farnsworth’s work, however, didn’t focus on direct research. And while there are exceptions, minimal analysis was done prior to the early aughts.

That’s when psychologist Sherry Benton, then at Kansas State University, authored a study that cracked open the field. Conversationally, people had been talking about “how ‘the problems are getting worse’ — noticing they were seeing more severe pathology in college counseling centers — since the late 1990s to 2001,” Benton says. “But no one had any actual data to verify it.”

Speaking by phone from Florida, where she is now the chief science officer for Therapy Assistance Online counseling, Benton also recalls a prevailing attitude toward student mental health that at the time was limited to homesickness, relationships and career decisions. “That was the illusion out there, that that’s what you got if you worked in a counseling center,” she says. “But if you think about it, most college mental health centers or counseling centers are basically serving the population of a small city, especially on larger campuses — so you see the full range of problems that you would anywhere else.”

Benton and her colleague Fred Newton analyzed more than a decade of data about students who visited Kansas State’s counseling center between 1988 and 2001 — more than 13,000 students, making it then the largest study of its kind. The findings, published in 2003 and widely reported in the media, were eye opening: In 13 years, the number of students seen with depression doubled, while the number of students with suicidal thoughts tripled. (Notably, instances of problems like substance abuse, eating disorders and chronic mental illness remained relatively stable.) Until 1994, relationship problems had dominated as the most frequent issue among students; in the years after, stress and anxiety issues prevailed. As a microcosm of college students nationwide, the findings suggested a trend worth examining further.

By the time Benton’s work was making headlines, the American College Health Association was a few years into administering its NCHA to college students nationwide, although it would be some time before its semi-annual collection of data could be parsed for trends. As more funding became available, other organizations affirmed and expanded what Benton uncovered.

Today’s leaders in campus mental health research include the Healthy Minds Network, a consortium of scholars working in public health, education, medicine and psychology, and the similarly multidisciplinary Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH). HMN launched its Healthy Minds Study nationally in 2007; like the NCHA, it asks about a range of health issues — topics like eating disorders, drug use, sexual behavior, nutrition and exercise — and seeks input from a general population of college students nationwide. CCMH, on the other hand, gathers input from college and university counseling centers, which means it focuses specifically on students who have sought treatment. It began gathering annual data sets during the 2010–11 academic year.

The research accumulated by these organizations paints a picture of college students’ increasing struggles with anxiety and depression. Take the NCHA: In spring 2009, almost 50 percent of students reported overwhelming anxiety, compared with 60.8 percent in spring 2017. (The survey was revamped in fall 2008, so earlier data can’t be used for comparison.) In 2009, nearly 31 percent of students said they were so depressed “it was difficult to function”; by 2017 that number had climbed to 39.1 percent. The number who seriously considered suicide rose from 6 percent to 10.3 percent in the same time frame.

CCMH, meanwhile, has seen slow but steady increases in the intensity of students’ self-reported anxiety and depression every year from 2010–11 to 2015–16 (the most recent data available) and the two were the most common concerns for students in 2015–16. CCMH also has seen slow increases each year in “threat-to-self” characteristics such as non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation. The number who seriously considered attempting suicide — 23.8 percent in 2010–11 — reached 33.2 percent in 2015–16.

So, how did we get here?

The answer is complicated. Cause is difficult to prove, though correlations can be found. Still, during the course of my conversations with experts and college administrators, several factors came up again and again — a stew of forces that have been at work on today’s college students since they were very young.

There is, to begin, the effect of large-scale societal events. These young adults, Benton says, experienced the 2008 recession through the prism of their families and came of age in a country that has frequently been saturated with news of terrorism and violence: “It’s those kinds of things that yank away people’s sense of predictability in the world,” she says. Benton’s Kansas State study bears out this point, with bumps in students’ anxiety and depression following the floods and foreclosures that consumed the region in 1993, and again after the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. The confluence of events in the early aughts is even more extreme. “You have a generation who grew up with less of a sense of safety and security than a generation ago,” she says.

They are also a generation that grew up with more parenting — the phenomenon of the so-called helicopter parent — a cultural shift that continues today. Julie Lythcott-Haims, a former Stanford administrator and author of How to Raise an Adult, has explored the subject for more than a decade. As she describes it, overparenting takes many forms, from hypervigilance around safety and intervening in playground squabbles when kids are young, to managing the constellation of hobbies, sports, academics and extracurriculars that make up their teenagers’ lives. Such pervasive control, she has found, deprives children of a chance to build life skills and develop confidence in their ability to be self-reliant; it also correlates with higher rates of anxiety and depression. “If we’re overhelped our psyche seems to know, ‘Hey, I didn’t do that myself. I’m not sure I’m capable,’ or ‘I might not have chosen that if it were up to me,’” says Lythcott-Haims.

Especially toxic, she notes, is a widespread culture of competition, exacerbated by a too-narrow definition of success: “A childhood that is about accumulating accomplishment and achievement in furtherance of getting into the ‘right’ college, which is heavily managed by parents who have those goals in mind, ends up being a childhood that deprives a young person of developing a self,” she says. “However accomplished these kids are on paper, however magnificent their achievements, they are thin at an existential level. They have not been permitted to be themselves; they have been honed into a champion human who looks a certain way outwardly but might be feeling pretty bewildered inside.” What’s more, if they haven’t had experience with failure, they might have trouble coping with setbacks.

Lythcott-Haims references her home community of Palo Alto, Calif., which is struggling to combat a youth suicide rate four to five times higher than the national average. “I think what we’re seeing with this helplessness and hopelessness that leads a young person to do the unthinkable — to have a sense of, ‘I’m not sure this life is worth living’ — I think it is related to, ‘I’m not sure this life is even mine.’”

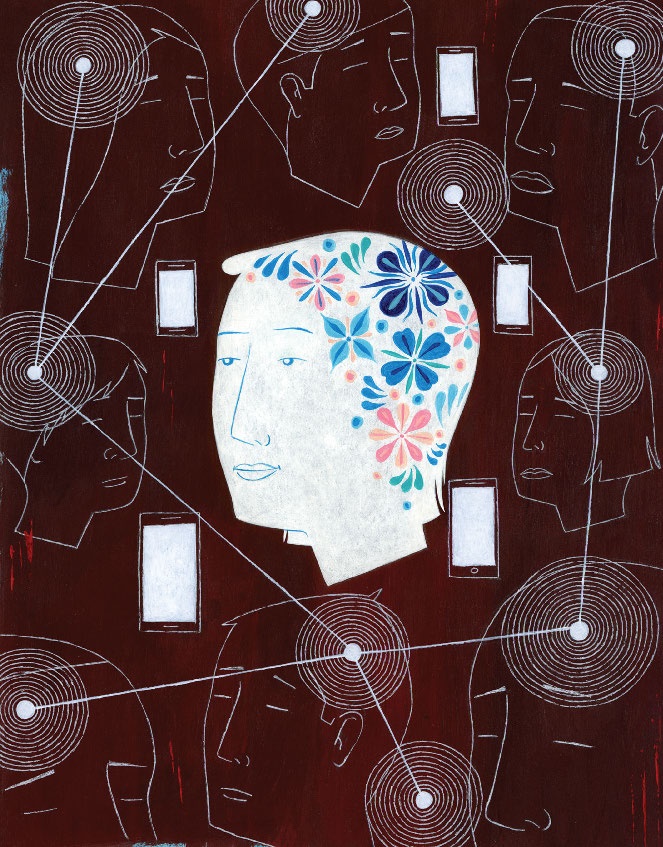

Then there is the smartphone. The now-ubiquitous technology has fundamentally changed the shape of young adulthood, from the way teens talk to one another to how they spend their free time. Jean Twenge, a professor of psychology at San Diego State University, examines the “earthquake” it and social media have unleashed in her recently published iGen. (The book’s title comes from the term she coined for the swath of young adults, born between 1995 and 2012, who will have spent the entirety of their adolescence in the age of the smartphone.) While the full psychological effects are still being determined, Twenge’s analysis, summed up in a September article in The Atlantic, suggests they are undermining teenagers’ well-being.

Among other things, Twenge cites the Monitoring the Future study — funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse — which asks teens about happiness and how much of their leisure time is spent on both non-screen activities (exercise, in-person social interaction) and screen activities (social media, texting, web browsing): “There’s not a single exception,” she writes. “All screen activities are linked to less happiness, and all non-screen activities are linked to more happiness.”

Her indictment continues: Loneliness is more common in teenagers who spend more time on smartphones and less time on in-person social interactions; the more time teens spend looking at screens, the more likely they are to report symptoms of depression; teens who spend three hours a day or more on electronic devices are 35 percent more likely to have a risk factor for suicide. Social media, meanwhile, has levied a psychic tax both on those who create posts (anxiously waiting for affirmation) and those who read them (who wind up feeling left out). The result, Twenge concludes, is a cohort of young adults who are “on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades.”

Have we really reached a crisis moment? Benjamin Locke, executive director of the Center for Collegiate Mental Health, pushes back against that characterization. He sees the statistics — at least in part — as a reflection of education around these issues, from the elementary school level on up, that has taken place during the last decade. “We’ve fundamentally changed the culture about mental health, help-seeking and stigma reduction,” he says. “And as a consequence of that we’re seeing growing demand.” The statistics also could reflect the fact that advances in diagnosing and treating mental illness have made it possible for more students with these struggles to attend college in the first place.

Locke resists the idea that students today are less resilient. “If you think about it, the students who are landing on campuses have been living in a competitive, self-comparative mindset for longer and more intensely than probably any prior generation of students,” he says. “They’re unbelievably resilient. But college is a massive life adjustment, and if there was anything that would bring out these maybe previously managed, normative experiences of depression and anxiety, it would be college.”

The college experience itself also brings stresses that students might feel more acutely today than in the past. Many face uncertainty around job prospects and what the economy will look like going forward. First-generation and low-income students might feel added pressure to succeed because of their backgrounds. High achievers, especially at top universities, can find themselves unmoored by the discovery that their intelligence and talent — an exception among their high school peers — is now the norm. The realization can set off something of an identity crisis: If I’m not “the smart one,” who am I? What do I have to offer?

As researchers continue to explore what’s influencing the well-being of our young adults, colleges and universities face an even more pressing question: What can they do to help?

“We want for everyone on campus to think that there’s a mutual responsibility to one another’s well-being.”

Ensuring the wellness of a campus is a big undertaking. So is wellness itself — an idea that encompasses all the ways people nourish their physical and mental health. For college students, yes, that can mean talking with a counselor when they feel overwhelmed — but also anything from eating right, exercising and getting enough sleep, to finding the right balance of studying and social time, to having a network of friends and engaging in positive relationships. Increasingly, Columbia and other colleges are looking holistically at how they can educate students about self-care, encourage them to prioritize it and create a culture that supports them in it.

“This growing concept of campus wellness is really about articulating value around all of the activities that we know promote wellness and helping students to value those because — historically — they probably haven’t been encouraged to value them,” Locke says. “They’ve been encouraged to value competition and taking on more and doing more and being successful, but actually, those things don’t lead to wellness.”

Confronted with a tide of anxiety and depression that has yet to turn, schools are responding in many ways. Some institutions have developed programs that teach students how to cope not only with academic stress, especially around failure, but also simpler setbacks like roommate difficulties or relationship frustrations. Examples include The Resilience Project at Stanford, Smith College’s Failing Well, the Princeton Perspective Project, Harvard’s Success-Failure Project and Penn Faces.

At Columbia College, a director of student wellness position has been created, and all staff now receive gatekeeper training, which teaches members of a community — including and especially non-health professionals — how to spot and respond to the warning signs of a mental health crisis. It also has partnered with The Jed Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting emotional health and preventing suicide among college students — founded by Phillip M. Satow ’63 and Donna Satow GS’65 — to review its undergraduate wellness services and programming, and develop a strategic plan for enhancing these efforts.

While programs like these allow students the opportunity to air out self-doubt, talk about their struggles and get out from under the façade of perfection, just as important is helping students understand that it’s normal to use mental health services when they’re having a hard time. “Nobody gets a clear sail through their entire life, at least no one I’ve ever met,” says Richard Eichler ’75, TC’87, executive director of Columbia’s Counseling and Psychological Services. “Stress can be associated with positive events as well as negative ones. Getting married, getting a new job, starting college, moving, having a baby — everything I’ve named is basically a wonderful thing, but they’re stressful in the sense that they place demands on a person. They challenge us. Some of what we [CPS] want to communicate is, it’s fine to get help if you’re dealing with those sorts of challenges, there’s nothing abnormal about it.”

Eichler has a long perspective on college student mental health, having worked at Columbia since 1986 and as the director of CPS — the only director it’s ever had — since its founding in 1992. In addition to its roster of psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers who meet with students, the center runs support groups and sponsors workshops that promote resilience and healthy coping strategies.

Eichler notes that the number of students who use the center’s services has more than tripled since its inception, but resists drawing a conclusion about whether that means students are more anxious or depressed today. “My strong sense is that whatever trends might exist in the general population, a big part of that [the increase] is people are willing to get help in a way that they weren’t 25 years ago, and the resources are much more robust and much more accessible … We — not just Columbia but all of our peer institutions and schools across the country — have devoted a lot more resources to building up these services and making them visible to students.”

CPS, for example, has established practice groups based on areas of special interest — topics like sexual and gender identity issues, multicultural concerns and trauma support. It has also made clinicians’ biographies available online, so students can easily read about their backgrounds and expertise. “All of this is a way of trying to be more responsive to students but also sending the message: ‘No matter who you are, you’re welcome here, and we have people who are likely to be able to understand your experience,’” Eichler says.

Though expansion and awareness of wellness-related services is critical, many health organizations believe that the psychological well-being of a campus is not the sole province of its mental health and counseling services. This more comprehensive, or “ecological,” approach calls for helping students develop independent living, social and emotional skills; fostering connectedness and belonging on campus; and reducing the sense of shame or secrecy that can come with personal struggle.

Eichler endorses the ecological model and sees it already in action around Columbia. “We want for everyone on campus to think that there’s a mutual responsibility to one another’s well-being,” he says. “And we want people on campus who become aware of a student in distress to feel that they have an awareness of the resources and the confidence to talk to that student about seeking out the resources they need.”

At the College, increased emphasis has also been placed on fostering connectedness. The Residence Hall Leadership Organization, for example, gives students an opportunity to get involved from the moment they arrive on campus, which can be especially important for first-years. And the group’s programming, in partnership with Alice! Health Promotion, includes social events on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights to help with community building.

“Small gestures of humanity and connection really go a long way,” Eichler says. “That’s some of what we’re talking about with a healthy campus. They can make people feel more at home and more connected.”

Back in Lerner Hall, the importance of helping the College’s newest students feel at home is acutely top of mind for Kromm and Patashnick. “We’ve been trying to build more programs that get smaller groups of students together during Orientation,” Kromm says. “So if you haven’t made your connection from your Orientation group or your residence hall floor, there might be another way to connect you.” She notes that the number of social identity mixers and “Community Unscripteds” — get-togethers focused around specific interests like music, activism or politics — both have been expanded.

Kromm also describes changes to the way the Orientation groups themselves work. In the past the small break-out groups met only twice; this year, they met six times, on the last day doing a reflection exercise. “These things aren’t mandatory, so you never know how many students are going to stick it out,” she says. “But on Friday as I was crossing campus, every group still had 10 or 11 students. It was a nice feeling of students really wanting to be part of that community.”

Feeling at home also means feeling supported, Patashnick says, pointing to the impact of gatekeeper training. “All our staff engage students on some level, so it’s important to us to make sure that everyone feels comfortable getting students connected to the right resource,” he says. “It’s a whole-community effort to care for the students.”

Kromm nods. “It has to be everyone.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu