|

|

|

|

|

COLUMBIA FORUMNicholas MiraculousExcerpts from Professor Michael Rosenthal’s biography of legendary Columbia President Nicholas Murray Butler (Class of 1882)

Michael Rosenthal Photo: Laura Butchy ’04 Arts

Few names are as synonymous with Columbia University as that of Nicholas Murray Butler (Class of 1882). Butler was University president from 1902–45 and died two years later, but not before transforming the University and earning himself an impressive level of national and international fame — and sometimes notoriety. To write the first substantial Butler biography, Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler, Michael Rosenthal, the Roberta and William Campbell Professor of Humanities, spent 12 years examining an enormous amount of research materials to create a definitive look at the man from his time as a student to the day he retired against his will. Although Butler’s name is heard on campus every day as students enter the eponymous library, few people today know much, if anything, about Butler and the ways in which he created much of Columbia as we know it. As Rosenthal notes (see page 29), Butler attained an impressive level of fame, then all but vanished into the collective history. Here, excerpts from the book highlight Butler’s time as an undergraduate; the pressure he felt to succeed and the effort he put into satisfying his family’s expectations; his election to Columbia’s presidency, succeeding Seth Low; and the pomp and circumstance that he brought to Morningside Heights.

A sketch of Columbia in 1891 with St. Patrick’s Cathedral in the background on the left.

The Columbia College that Butler found that fall [1878] bore little resemblance to the university he left behind him in 1945, physically, academically, or in any other way. Having moved north from Park Place in lower Manhattan in 1857, the School of Arts, as the liberal arts undergraduate division was then called, occupied the block between 49th and 50th streets, stretching from Madison to Fourth [now Park] Avenues, on a site purchased from the Lexington Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. Initially conceived of as a temporary location, it remained Columbia’s home for 40 years. Its neo-Gothic campus, completed during Butler’s four years there, included a library, a chapel, a house for the president, a building for the School of Mines, and one for the instruction of the School of Arts students. There were no dormitories and no playing fields. Although the surrounding environment had improved by the time Butler arrived, it was still not entirely salubrious. Before the bodies were removed during 1858, students coming across Lexington Avenue and 49th Street, one block to the east of the campus, could occasionally see the bones of the indigent sticking up out of Potter’s Field. The Bull’s Head Cattle Yards, several blocks south on Fifth Avenue, lent olfactory pungency to the academic enterprise when the climatic conditions were just right. Butler was one of 78 entering students in the Class of 1882; four years later, 48 graduated. We have become so accustomed to thinking of elite colleges as intellectually rigorous places, admitting only a lucky few from the hordes who apply, that it is important to realize that in Butler’s time — and for a number of decades thereafter — the problem facing colleges was not the contemporary challenge of deciding among qualified students, but rather the need to convince qualified, and even not so qualified, candidates to apply in the first place. Only a small number sought admission; of these, few were rejected. In Butler’s freshman class, for example, 100 initially applied, and 75 were accepted. Three additional students joined somewhat later. In the late nineteenth century, most undergraduates attended schools within 100 miles of their homes. The absence of dormitories guaranteed the parochial nature of Columbia’s student body. Of Butler’s original 77 colleagues, only 16 were not from Manhattan, coming instead from such exotic places as Brooklyn; Yonkers; New Jersey; Greenwich, Conn.; and even Tarrytown, N.Y. Once admitted, and for an annual tuition fee of $100, Butler and his fellow students immersed themselves in a required curriculum (with the exception of some senior-year electives) taught by a faculty consisting of 10 professors, two adjuncts (today’s equivalent of assistant professors), and a half dozen or so assorted tutors and assistants. The precise syllabus for each year, semester by semester, was set out in the informational handbook. The freshman studies Butler encountered in the fall, for example, included the Odyssey, Greek prose composition, Greek scanning and prosody, Horace’s Odes and Epodes, Latin prose composition, Latin syntax and prosody, Grecian history, Roman antiquities, geometry and rhetoric, with German as an optional choice. The spring continued Greek and Latin prose composition, Grecian history, rhetoric and Roman antiquities, but substituted Herodotus or Xenophon for Homer, algebra for geometry, and Cicero and Pliny for Horace.

Butler as a College senior in 1882.

If one actually had to know something to get into Columbia, little was expected after that. Classes ran for three hours a day only, from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., following the mandatory chapel service that started at 9:40. Students sat in alphabetical order in the chapel, and class officers specially appointed by the president took daily attendance. The four officers of the roll were each provided with a seat permitting a full view of his particular class. Anyone absent from more than one fourth of the chapel exercises for a term was “debarred from being any longer a candidate for a degree.” (Other infractions that could terminate enrollment included leaving the college premises before the end of the third hour and missing more than one quarter of the classes in any single department.) The classes themselves were never intended to be intellectually challenging. They consisted almost entirely of students spewing back in recitation sections that they had previously memorized from the textbooks or the professor’s lecture. Independent thinking was rarely a requirement, and academic standards were practically nonexistent. Whether standards should exist at all had in fact provided a legitimate issue of trustee inquiry some twenty years before Butler entered. In a report published in 1858, a committee of five trustees debated “whether public opinion would sanction a strict course, and whether, to avoid a large diminution of students, allowance ought not to be made for defect of intellectual capacity, imperfect elementary training and inattention or indifference of parents as to the studies of their sons.” Should standards be set too high, it was argued, “you might exclude students of dull or slow minds, who are yet faithful and diligent.” Such an exclusion would clearly affect the tuition revenues on which the school depended. On the other hand, although enforcing standards could result in a loss of potential students, it might also prove beneficial by convincing skeptical families that Columbia was actually trying to train their sons to some purpose, thereby attracting students who might otherwise have been sent elsewhere. A similar argument presented itself concerning admissions: Should Columbia admit even the deficient, on the grounds that they might improve, or should applicants be held to a serious level of preparation and achievement? In both cases the claim for some form of standards triumphed, but that these issues should have been debated at all raises disturbing questions about what sort of institution Columbia was at the time.

The reading room of the Columbia College Library on the 49th Street campus, circa 1887.

Into what he later characterized as “a very simple and naive sort of place,” Butler brought a prodigious memory and ferocious desire to succeed. The latter was nourished by family expectations. After the sudden death of his uncle Chalmers, the burdens of achieving Butler distinction passed to Murray. A letter from Uncle Chalmers’s father during the spring of Murray’s freshman year declared the responsibilities he was now expected to meet:

Murray took seriously his obligation to excel, working hard to remain always at the top of his class, even if it meant putting his health at risk. “Murray we see only on Sundays,” step-grandfather Meldrum reported in 1881. “He is thin, and troubled a good deal from nose bleeding, but sticks to his work as determinatedly [sic] as ever.” Butler’s obsession with getting the highest grades — a trait that earned him, in the student jargon of the time, the title of “champion bun-yanker” — did not, however, preclude his participation in a variety of collegiate activities. Despite the lack of facilities, undergraduate existence, according to Butler’s good friend Harry Thurston Peck, “was full of interest and color and animation,” and Butler enthusiastically engaged as much of it as he could. As an editor of Acta Columbiana, the college newspaper, he praised the freedom Columbia men could enjoy without the constraints of dormitory living, and he criticized coeducation for turning out “brazen, mannish and unfeminine females.” He served as sophomore class secretary; edited the Columbiad, the junior class yearbook; and created the fictitious S.P.Q.R., a nonexistent organization intended to draw attention away from the Gemot, a real club to which he had not been admitted. He was a member and officer of Peithologia, one of the two literary debating societies on campus. He drafted the 1882 class constitution and wrote a resolution passed unanimously by the senior class against admitting women to Columbia, which held that “it is the fixed opinion and firm conviction of the Senior Class of Columbia College that the coeducation of the sexes is undesirable from an educational as well as from a social and a moral standpoint, and that its introduction here would be a fatal blow to the future welfare and prosperity of the institution.” He played cricket (badly), was rejected for football and crew because he did not weigh enough, and acted as secretary of the college meeting to form a football association. (His role in helping form the association is particularly interesting in light of his presidential decision, in 1905, to ban the game.) Before he became appalled by its professionalism and violence, in fact, he seemed particularly to enjoy football. He wrote his mother with obvious relish in 1879 about a trip to Princeton to see Columbia play. As Princeton “ ‘runs the racket’ on football,” little was expected of Columbia, and Butler delighted in his team’s gritty effort: “Dave said he never saw such ‘tackling’ as Henry and DeForest could do; it was funny to see those comparatively little fellows catch Ballard & Pease round the neck & throw them ‘heels over appetite.’” Columbia’s inevitable loss didn’t diminish the expedition’s pleasure: “‘We went, we saw, we (got) conquered,’ but we got a good day’s fun.”

The farmland that Butler would turn into South Field after he became Columbia’s president in 1902.

Perhaps the most lavish event involving Butler was the annual sophomore “Burial of the Ancient” ceremony, whose origins dated back to 1860, in which the textbook deemed most hateful to the sophomores was consigned to flames amid much elaborate ritual. For a number of years the book so honored had been Bojesen’s Grecian and Roman Antiquities, but Butler’s class chose instead March’s Anglo-Saxon Reader. Butler was elected chairman of the burial committee in charge of the extensive preparations necessary for a successful burial. As the Acta cautioned in April — the event was scheduled for May — “The sophomores must take care to deck themselves out well at the burial. Every man should wear a high hat and a gown with emblematic figures attached. It gives more tone to the procession, and looks well to outsiders, besides the over-awing effect it has upon the freshmen. A burial is a grand thing when every minute detail even is carefully attended to, but if only the principal points are looked after, many things fail to harmonize, and the general effect is marred.” With Murray at his organizational best, everything proceeded flawlessly, particularly the two-hour march up Madison Avenue to the campus, including a platoon of police, a German brass band, a trumpeter, twelve mourners wearing academic gowns adorned with skulls and crossbones, four pallbearers chanting funeral songs and carrying in a small bier on their shoulders the loathed Anglo-Saxon Reader to be consigned, and three hundred torchbearing students wearing their coats inside out. Accompanied by masses of spectators waving, singing, and cheering, the procession arrived on campus at midnight, where the Deadly Orator addressed the crowd, expressing his feelings about the soon to be cremated text. At the proper moment, the Gravedigger committed March’s reader to the flames, after which the Poet, wiping his eyes with a huge black handkerchief, celebrated the many virtues of the recently departed. Following appropriate cheering and lamentation, people repaired to the Terrace Gardens, where the twenty previously purchased kegs of beer were consumed. “Thus,” commented the June 1 Acta, “passed off the best and most successful Burial that Columbia has ever seen, and it will be a long time before it is surpassed.”

More than simply a personal tribute to Butler, Roosevelt’s participation also spoke to the significance of Columbia.

Low [University President Seth] understood that accepting the [1901 New York City mayoral] nomination would mean leaving Columbia. In 1897, the trustees had agreed to defer action on his resignation until the outcome of the election was known, but he realized they could not be expected to do this a second time. As his resignation letter of September 25, 1901, to the trustees stated, with typical humility, “Columbia University cannot teach men to be patriotic if it will make no sacrifice in the public interest; and not even Columbia’s President can expect to be exempt from the obligation to illustrate good citizenship as well as to teach it.” On October 7, his resignation accepted, Low officially said goodbye to students and faculty in a packed University Hall. Stressing his deep feeling for the university, Low explained the pull of duty that required him to “burn his bridges behind him” so that he could function in the coming political campaign without compromising the institution that was so firmly embedded in his heart. After his farewell, with a cry of “Six Columbias for ‘Prexy Low,’ ” followed by “Low, Low, Low,” Seth Low left University Hall, his 12-year presidency over.

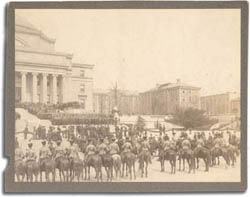

Squadron A accompanies President Theodore Roosevelt and former New York Mayor Abram S. Hewitt up Fifth Avenue to attend Butler’s installation as Columbia’s president, April 19, 1902.

The choice of acting president was no more complicated than had been the choice of the man to sign Low’s letters in his absence some 10 months before. Trustee conversations in September, as they contemplated Low’s impending resignation, had never seriously questioned that Butler was the obvious temporary replacement while a search was conducted for a permanent president. As chairman of the board William Schermerhorn wrote to John B. Pine, “Professor Butler is undoubtedly our best man, and indeed his qualifications for the higher office seem to be not a few.” Butler began his new job on October 8. Earlier in the week, Schermerhorn appointed a search committee consisting of himself, Morgan Dix as chairman, Edward Mitchell, George Rives and Pine to bring before the entire board one or more names to fill the vacancy caused by Low’s departure. All five were predisposed to Butler, but Pine, his college friend and clerk of the board, would have to be thought of as an active agent on his behalf. However judiciously Pine conducted himself with his colleagues, it was apparent from the beginning that he intended to guarantee that the search would end with the election of Nicholas Murray Butler as the next president. Even before the committee held its first meeting, Pine asked Low to help influence its deliberations in a way that almost bordered on the unethical:

Such support from Low at the start, Pine continued, would have the further benefit of enabling Pine “to be able to state when a conclusion is reached, that the Trustees have chosen the successor whom you yourself selected, not only as a mark of respect to you, but because such an announcement will be gratifying to the Trustees and to your successor.” On November 2, Low told Pine that he did not yet have the time to give his letter proper attention, but that his general principle was to refrain from becoming

Roosevelt’s procession arrives at Low Library.

Meanwhile, as Low skillfully avoided taking a position on Butler’s candidacy, enthusiastic letters of praise reached Pine from Butler’s friends around the country. And not just any friends, of course, but people like the freshly minted president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt; commissioner of education William T. Harris; Presidents Harper of Chicago, Eliot of Harvard, and Draper of Illinois; Newton C. Dougherty, superintendent of schools in Peoria, Ill.; and Irwin Shepard, secretary of the National Education Association. It is difficult not to feel the encouraging presence of Pine (and, of course, Butler himself) behind these “unsolicited” recommendations. In addition to the President of the United States and the commissioner of education, they happened to represent all the different educational constituencies of the country in whose opinions the trustees might be interested: public universities (Draper); private universities (Eliot and Harper); and the thousands of public school teachers, administrators, and educators involved in the grassroots problems of secondary education (Dougherty and Shepard). Hardly a random group supporting Butler’s candidacy. By late December, Low finally wrote to Dix, as Pine had requested he do in October, urging that Butler be appointed as soon as possible:

To delay, Low worried, would make it harder to fill Butler’s professorial place and would suggest that the trustees had entertained doubts about their decision. For Low, the sooner the better; he saw no reason why Butler couldn’t be elected in January. Low’s letter was decisive. Pine got it from Dix on December 28 and distributed it to the rest of the nominating committee in time for its scheduled meeting on December 30. Rives could not attend, but he permitted his name to be added to those of the other four in unanimously agreeing that after “mature deliberation and a full discussion … they have concluded to nominate Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler to the office of President, and accordingly, they now present his name for the consideration of the Trustees.” On January 3, 1902, Pine reported to Low the good news about the nominating committee, adding, “Your letter to Dr. Dix was undoubtedly influential in bringing about this happy result, and I have taken the liberty of sending copies of it to many of the Trustees as well as to members of the Committee.” Having heard that Low might not be free to attend the full trustee meeting on January 6, Pine expressed his hope that he would manage to stop by, if only during the early part, when the nominating report would be considered, “to help launch your successor.” Whether because of strict compunction about his mayoral duties, or whether he had at the last instant a twinge of doubt about his successor — or at least the propriety of voting for him — Low declined to miss or cancel a board of estimates meeting that same afternoon. In an oddly reluctant way, he advised Pine to “make my excuses. You are at liberty to say, if the report of the comtee. comes to a vote, that if I were present I should vote for Dr. Butler for the presidency, with pleasure.” Low’s absence notwithstanding, his pleasure at Butler’s election apparently was real. “The morning after Nick Butler was elected,” George McAneny reported, “Low came in rubbing his hands and was greatly pleased. He said, ‘It isn’t given to every man, McAneny, to be able to choose his own successor so well and so happily.’ ” With Low’s support, then, but without his actual vote or presence, Nicholas Murray Butler shed his “acting” title to become the twelfth president of Columbia on January 6, 1902. Saturday, April 19, 1902, was crisp and sunny, the perfect day for a garden party — or the inauguration of a new university president. The trustee committee responsible for choosing Butler’s installation date could not take credit for the lovely weather, but they did have a serious reason for selecting this particular Saturday. The decision, Pine laconically commented on February 3, “was influenced somewhat by the fact that the committee were able to obtain assurances of the presence of the President of the United States, the Governor of the State and the Mayor of the city at this time.” Roosevelt’s attendance, courtesy of his friendship with Butler, itself guaranteed the auspiciousness of the occasion. More than simply a personal tribute to Butler, Roosevelt’s participation also spoke to the significance of Columbia. As one editorial writer noted, it was most unusual to have a mayor, governor, and president sitting on the same platform celebrating a university that all three had attended. (Low had graduated from the college; Governor Benjamin Odell had taken an engineering course in the School of Mines; Roosevelt had spent a year in the Law School.)

Butler’s 1902 portrait as Columbia’s 12th president.

The formal ceremony was scheduled to begin at 2:30 p.m. in the University Hall gymnasium, but the day’s festivities began when Roosevelt, sporting a brand-new top hat and yellow spring coat, arrived in New York by ferry from Jersey City at 6:30 in the morning and went immediately to his aunt’s house on the East Side, where Butler joined him for breakfast. Shortly before noon, after Butler had left to deal with university business, Roosevelt, along with former mayor Abram Hewitt, entered a horse-drawn carriage to begin their procession up Fifth Avenue accompanied by four troops of Squadron A, a cavalry unit of New York’s National Guard, in full-dress uniform. Brandishing swords held stiffly upright against their shoulders, swaddled in tightly fitted double-breasted tunics, festooned with quantities of braid, and wearing large black fezlike hats jauntily displaying a kind of feathered cockade sticking out of the top, they looked like nothing other than extras from a Franz Lehár operetta. They inadvertently added a touch of useful old-world pomp as they escorted the carriage to Morningside Heights. Following three separate luncheons — one given by the trustees for Roosevelt and those speaking at the ceremony, one by the University Council for the participating college and university presidents and their representatives, and one for university marshals and the men of Squadron A — the members of the academic procession assembled in Low Library and shortly before 2:30 marched around the library to University Hall, located directly behind it. The Times pointed out that New York had never seen an academic pageant quite like it. In addition to the President — the first time since the first year of George Washington’s administration, it was noted, that a president of the United States had paid an official visit to Columbia — and the governor and mayor, distinguished marchers included Senator Chauncey Depew; the German ambassador; the British scientist Lord Kelvin; forty-eight college and university presidents; the U.S. commissioner of education; the postmaster general; William Howard Taft, then governor-general of the Philippines; and the librarian of Congress. Andrew Carnegie, not part of the procession, sat in the audience. Altogether, close to 3,000 people packed the beribboned and bedecked University Hall (whose preparation and dismantling cost $4,008) for the installation. They witnessed a dignified program, framed by opening and closing prayers and containing the presentation to Butler of the University Charter and Keys. Ten separate speeches were delivered (including Butler’s inaugural address) as well as greetings from the presidents of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Chicago, and Butler’s old friend William T. Harris. Throughout the proceedings Butler remained prominently seated, except when giving his address, in the “President’s Chair,” once the property of Benjamin Franklin. President Roosevelt did not speak but instead silently endured the two-and-a-half-hour ceremony, surely one of the few times that the President had been invited to attend a public event of this importance without being asked to say anything.

Butler at his last commencement, June 6, 1945. Photos: University Archives and Columbiana Library, Columbia University in the City of New York

At 5, after the singing of “My Country ’Tis of Thee” and a closing benediction by Bishop Horatio Potter, 500 selected guests left the proceedings for Sherry’s restaurant and an elaborate banquet hosted by the alumni for Butler. Amid much blue and white bunting — Columbia’s colors — and the flags of other American universities, more encomiums were lavished upon Butler. Songs were sung, oysters and filets of bass and boeuf were devoured, and of course more addresses — eight this time — offered. Here TR at last got his chance to orate, stressing his favorite theme of the importance of character over intellect. By the end of the evening, as the well-fed and well-talked-at alumni and guests dispersed, it would have been difficult for them not to have been caught up in a haze of warm feelings for Columbia and its new president. Butler accepted his new responsibilities without any discernible doubts or anxiety. Nothing appeared alien to him, and there was nothing, Butler made it seem, he couldn’t accomplish. Henry Fuller, Butler’s uncompromising enemy during New York’s public school wars of the 1890s, put it as well as anybody by suggesting that “if the Higher Powers would entrust him with the task of constructing a new universe, Professor Nicholas Miraculous Butler would enter upon that undertaking with equal confidence, unabashed and unaided.” It cannot be known whether Butler, if given the necessary materials, could have created a new universe, since for some unaccountable reason the Higher Powers decided not to risk it. What is clear is that the Columbia trustees were more daring than the Higher Powers. Handing Butler the materials of a small school, they watched admiringly as he made for himself a powerful empire of education, not unlike “The Empire of Business” forged by his friend Andrew Carnegie. In turning Columbia into one of the largest and best-known universities in the world, he served the longest tenure of any University president. “The surest pledge of long remembrance among men,” Harvard’s president Eliot wrote, “is to build one’s self into a university.” Eliot was wrong about the perpetuity such a connection guaranteed, but it is the case that no one ever built himself more tightly into an institution than Butler did at Columbia. Once there, he had no intention of leaving. Had the trustees understood the tenacity of his attachment, it would have come as no surprise to them that more than four decades later, blind and deaf, Butler had virtually to be pried out of his position by the next generation of the board. Retirement from Columbia was never part of his plan. He would have much preferred to die in office. Reprinted with the author’s permission from Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35). See Bookshelf.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||