|

|

|

|

|

|

|

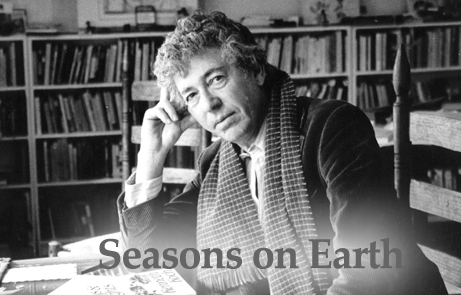

Kenneth Koch's Seasons on Earth By David Lehman '70 In one of his last “seasons on earth,” Kenneth Koch went to the Anderson Cancer Center in Houston to undergo radical treatment for the leukemia that had stricken him in the summer of 2001. For weeks, he was confined to an isolation chamber. The treatment was painful, the odds of its working less than even. But the irrepressible poet and beloved Columbia professor had learned that the hospital had a poetry writing program — the sort of program that had become popular nationwide as a result of Koch’s pioneering books, Wishes, Lies, and Dreams: Teaching Children to Write Poetry (1970) and Rose, Where Did You Get That Red?: Teaching Great Poetry to Children three years later. A pair of Houston-based poets came to the hospital weekly to teach poetry to schoolchildren diagnosed with cancer. Through a glass partition, Koch met with the teachers to give them pointers. He asked a friend, poet Paul Violi, to fax him his favorite translation of Cecco Angiolieri’s sonnet, “If I were fire, I’d burn the world away,” When Violi commented that the poem might be too harsh for such young kids to imitate, Koch said, “Paul, you don’t realize how angry these kids are.” That is one of the things that Koch — who died on July 6, succumbing to the leukemia he had fought for a year — had figured out for himself and his students long ago: Anger is useless, but you can transmute it into something beautiful or charming or funny or true. Not that therapy is the primary goal; it is just a beneficial byproduct of the process. The primary goal is poetry, which can be written anywhere, by anyone, and is properly understood as a celebration of itself and all creation. Poetry was what happened when you liberated the imagination. Poetry was joy, and what’s more — and contrary to some highly publicized cases of suicidal, despondent or deranged poets — you didn’t need to be in agony in order to write it, and you didn’t need to show a solemn face to the world. Koch had liberated the imaginations of Columbia undergraduates since joining the English faculty in 1959. At first he taught, in addition to literary humanities, a course on comedy in modern literature that soon became legendary. “I still know the reading list by heart,” said Ron Padgett ’64, one of the first of the poets whose lives Koch changed. Padgett reeled off the titles: “Ulysses as a comic novel (not the way it was taught in modern literature courses); Jarry, Ubu Roi; Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons; Svevo, Confessions of Zeno; Evelyn Waugh, Vile Bodies; Aldous Huxley, Crome Yellow; Ronald Firbank, The Flower Beneath the Foot; Borges, Ficciones.” The comic impulse is still underrated, perhaps especially in poetry, and Koch knew that he was risking instant critical dismissal by making some of his own poems so funny. But Koch was intrepid, and his comic originality never deserted him.

Comedy, for Koch, was life itself, but it also could coexist with ire. In “Fresh Air” (1956), Koch used it to turn a rant into a vision or prophecy. Envisaging the enemies of poetry to be tweedy professors, Koch unleashes a comic-book hero called “the Strangler” to get them: “Here on the railroad train, one more time, is the Strangler. / He is going to get that one there, who is on his way to a poetry reading. / Agh! Biff! A body falls to the moving floor.” Born in Cincinnati in 1925, Jay Kenneth Koch couldn’t wait to grow up. “The whole idea of writing poetry has a lot to do with escaping,” Koch liked to say, and Cincinnati (and provincialism in general) was what he wanted to escape from. Drafted into the Army, Koch saw action in the Philippines. He wrote movingly about the experience in “To World War Two.” The conceit of this poem, as of all the poems in New Addresses (Alfred A. Knopf, 2000), is that it is a direct address to an abstract entity, in this case, World War II: One, in a foxhole near me, has his throat cut

during the night In putting to such brilliant new use the rhetorical device known

as the apostrophe, Koch reveals a strength of his poetry that permitted

him to be so inspiring a professor. Able to reinvent or reinvigorate

a form, he produced poems that were exemplary but didn’t exhaust

the possibilities that his formal ingenuity had laid open. [ 1 | 2 ] |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

PHOTO:

CHRIS FELVER

PHOTO:

CHRIS FELVER Koch’s poetry sometimes commences in parody or satire and

ends nevertheless in a sublime peak of wonderment. His first book,

Ko, or a Season on Earth (1959), a comic epic in the jaunty

manner (and meter) of Byron’s Don Juan, established

Koch immediately as a poet of pleasure, and it demonstrated, too,

his lifelong interest in enlarging the bounds of contemporary poetry,

not limiting it to the ubiquitous brief anecdotal first-person lyric.

Written in a seemingly effortless ottava rima, the poem

begins audaciously with the word “Meanwhile.” Simultaneity

is its operating principle. It celebrates all sorts of things that

are happening at once, from baseball games and love affairs to foiling

the nefarious designs of the villain, Dog Boss, who wants to control

all dogs on earth. In the poem’s first canto, the high school

girls of Kansas go on a nudity strike to protest the dullness of

life. Here was a species of imaginative wish-fulfillment that doubled

as a dream of American innocence.

Koch’s poetry sometimes commences in parody or satire and

ends nevertheless in a sublime peak of wonderment. His first book,

Ko, or a Season on Earth (1959), a comic epic in the jaunty

manner (and meter) of Byron’s Don Juan, established

Koch immediately as a poet of pleasure, and it demonstrated, too,

his lifelong interest in enlarging the bounds of contemporary poetry,

not limiting it to the ubiquitous brief anecdotal first-person lyric.

Written in a seemingly effortless ottava rima, the poem

begins audaciously with the word “Meanwhile.” Simultaneity

is its operating principle. It celebrates all sorts of things that

are happening at once, from baseball games and love affairs to foiling

the nefarious designs of the villain, Dog Boss, who wants to control

all dogs on earth. In the poem’s first canto, the high school

girls of Kansas go on a nudity strike to protest the dullness of

life. Here was a species of imaginative wish-fulfillment that doubled

as a dream of American innocence.