|

|

|

|

|

|

|

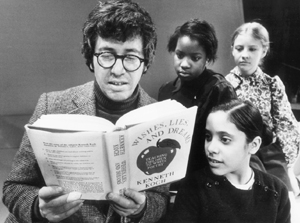

KENNETH KOCH'S SEASONS ON EARTH [ 2 OF 2 ] After being discharged from the Army, Koch went to Harvard on the GI Bill, graduating with honors in 1948. It was there that he met fellow poet and lifelong friend John Ashbery. Their friendship, transplanted to New York City in the 1950s, branched out to include poets Frank O’Hara and James Schuyler as well as painters Larry Rivers, Jane Freilicher and Fairfield Porter. These witty and complex personalities formed the heart and soul of the New York School of poets.

Unlike his cohorts Ashbery and O’Hara, who earned their living as professional art critics, Koch pursued an academic career, doing so with the gusto of a bon vivant. On a Fulbright Fellowship, he went to Aix-en-Provence and hung out at the Cafe Deux Garçons instead of attending lectures on explication de texte. He enjoyed the sound of spoken French and the experience of not understanding, misunderstanding, or partially understanding what he heard. He tried, he later remarked, to inject the “same incomprehensible excitement” into his own work. At UC Berkeley, where he studied briefly, he met his first wife, Janice. They honeymooned in France and Italy and spent more than a few fellowship seasons in Europe. Their daughter, Katherine, was born in Rome in 1956.

Koch was a natural in the classroom. Flamboyant, charismatic, spontaneous, he could improvise lessons in blank verse or leap to his feet and caricature a mustachioed German dictator if the anecdote called for it. He got students to write poems on the spot, individually or as a group, and other things we didn’t think we could do. He made us realize that the writing of poetry could be done under any circumstances and could still retain a quality of mysteriousness and magic. Bruce Kawin ’67 likened Koch to a sorcerer. “And we’re his apprentices,” Kawin said. I took Koch’s writing seminar (he hated the word “workshop,” even when used as a noun) in 1967–68. Kathy Shenkin Seal ’69 Barnard remembers how entertaining the sessions were. “Sometimes I giggled through the entire class,” she says. “Once, Koch fell on the floor laughing at his own joke. Another time, he composed a poem about my being late to class.” But Koch couldn’t have had such a hold on his students if he hadn’t also been (as Seal wrote in her journal in 1968) “so extremely kind and gentle and caring for other people’s feelings.” In his writing classes, Koch would give very specific, highly detailed assignments. We had to write poems or stories in imitation of certain authors (William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, John Donne, Wallace Stevens, Boris Pasternak) and in set forms (sestina, blank verse, sonnet, prose poem). At the start of each class, Koch read aloud the best poems turned in the previous week. His enthusiasm and his conviction were great spurs to creativity, as was the growing sense of competition that emerged, everyone hoping his or her work would be read aloud in class. Koch always felt that the most fortunate thing ever to happen to him as a poet was to have, in his words, “three close friends who were so good [at writing poetry] it scared me,” and he didn’t mind instilling in us a bit of that kind of intense friendly rivalry.

Michael Paulson ’04 told me he enjoyed imitating Gerard Manley Hopkins, especially because he felt it gave him “free range to indulge in the most outlandish language.” Paulson could have been speaking for many when he added, “While the assignments were always fantastic, it was the presence of the man himself — his words, his speeches, his advice — that really changed my life. I could sum up the course and its effect on me as one grand assignment: You are going to be a poet. You have to be a poet. There’s really no choice in the matter, so you might as well get cracking.” Jessica Greenbaum ’79 Barnard has a file of memorable mantras from the master — “Find one true feeling and hang on,” “Poems don’t have to end with the crashing of the ocean” — but in the end she feels that “the example he set for students in his work was the most long-lasting of the writing assignments he offered me.” Mark Statman ’80 recalled “reading Hemingway’s beautiful In Our Time and learning to write sentences that were simultaneously soft and tough. But what I remember most was how seriously Kenneth took us as poets, as writers, and how much he paid attention to what we were doing. I remember conversations with him when it seemed he knew more about my writing than I did.” Statman’s life changed in more ways than one. He married Katherine Koch, and they are the parents of Koch’s grandson, Jesse. Teaching literature, Koch warned against jargon and symbol-hunting and urged us to have an individual, almost sensual, relation to the work at hand. Ariana L. Reines ’02 Barnard took Koch’s “Modern Poetry” course. “There was a youthful, sometimes aphoristic, all right, Wildean brilliance about the way he managed to speak so simply” about complex poems, she says. Rachel DeWoskin ’94 recollects Koch’s dry rejoinder to the student intent on seeing “an angry penis” in a D.H. Lawrence snake: “There are a limited number of shapes in the world.” Koch loved literature for itself, and not as fodder for dissertations. Jessica Greenbaum: “More than anyone else I can remember, he talked about beauty.” Ron Padgett: “He loved what he taught, he radiated that love, he was enthusiastic, smart, open, serious, funny, tough, generous, and inspiring, and he gave me the feeling that it all mattered.” “Kenneth Koch was my favorite teacher ever, period,” says Richard Snow ’69, who became editor of American Heritage. Not only was Koch “wonderfully funny” and “wonderfully imaginative,” but “his own furthest excursions into the fantastic were always underpinned by a perfect understanding of and respect for the mechanics of the English language. My papers would come back to me dark with notations, hastily written but beautifully expressed, always summoning me to attend to proper workings of prose, pointing out grammatical laxities as well as the hundred varieties of sentimentality that the neophyte poet can be prey to. I have spent my working life as an editor and, to a lesser extent, as a writer, and more than anyone else, it is Kenneth who equipped me to do this. I am very much in his debt.” To the question, “What inspired you the most?” David Shapiro speaks of Koch’s “total commitment to poetry.” No one who knew him ever doubted his seriousness about poetry, its importance in the life of a poet, and its great cultural value. It seemed to inform his most casual observations. When he visited the leafy New England campus of Andover Academy, where Jeffrey Harrison was teaching, a gigantic old elm caught his eye. He got very excited, Harrison remembers. “It’s like a really complicated stanza pattern,” Koch said. The energy of the man was great, his wit formidable under pressure. When Paul Violi visited him in the hospital in New York, Koch introduced the portable IV stand he was tethered to as “Duchamp’s sister.” Professor of English and former dean Michael Rosenthal was Koch’s colleague for more than three decades. At the hospital, the old friends munched on Mondel’s dark almond bark and “talked for two hours about Dupee and Columbia and [Lionel] Trilling [’25] and our various bizarre experiences. There was not an instant of self-pity or despair, just mad humor. He was glorious.” “It was amazing,” poet (and newly appointed president of the Guggenheim Foundation) Edward Hirsch remarked about Koch’s efforts to nurture the poetry-writing program in the Houston cancer ward. “Even though he was so ill, he clearly saw it as part of his mission, part of his legacy, to bring the gift of poetry to people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to express themselves.” Through his teaching, and his books on teaching, Koch probably has influenced as many readers as has any American poet of his generation. It was also through his teaching that he met his second wife, Karen. (Janice Koch died in 1981.) Karen was working for an educational consulting agency in Pennsylvania that hired the renowned Columbia professor to teach the teachers: “I had never heard anybody make such sensible statements about how to write poetry and certainly how to teach it,” Karen Koch said. The couple wed in December 1994. Though he won many awards for his poetry (the Bollingen in 1995, the Bobbitt in 1996, the Phi Beta Kappa Award last year) and attracted many devoted and accomplished disciples, he ran the risk that recognition of his teaching would overshadow all else. Koch’s poetic genius has not yet received its full due, but that is coming as a new generation of ambitious readers discovers the poets of the New York School. They will find in the poetry of Kenneth Koch a self-replenishing fund for invention. It was Koch who more or less created the one-line poem as a genre (see his Collected Poems) and refreshed the Whitman catalogue as a poem’s organizing principle (“Lunch,” “Some General Instructions”). He showed that a poem could take the form of a play (“Pericles”), a diary (“The Artist”), a bawdy treatise on love (“The Art of Love”), a parodic impersonation (“Variations on a Theme by William Carlos Williams”) or an intimate conversation with an abstraction (“To Psychoanalysis,” “To Jewishness,” “To Kidding Around,” “To the French Language,” “To High Spirits,” “To Old Age”). As the sequence of titles in the last parenthesis implies, Koch’s New Addresses, published when he was 75 and still as youthful as ever, subtly intimates an autobiography without ever stooping to the tactics of confessionalism. Koch was never one to tolerate what he called “kiss-me-I’m-poetical junk.” Better teacherly advice you cannot receive than that offered in Koch’s The Art of Poetry: Poems, Parodies, Interviews, Essays, and Other Work (University of Michigan, 1997). Koch held up the highest standards of poetic excellence to his students; he practiced them; and in the end he was able to write as few can, with the wit that comes from truth-telling and the eloquence that comes from simplicity, of the final human predicament: The dead go quickly |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At Columbia, Koch earned a master’s degree with a thesis

on the figure of the physician in dramatic literature. His 1959

doctorate, on poetic influence as a two-way street between the United

States and France, followed. Professor Frederick Dupee’s enthusiastic

support helped gain Koch tenure.

At Columbia, Koch earned a master’s degree with a thesis

on the figure of the physician in dramatic literature. His 1959

doctorate, on poetic influence as a two-way street between the United

States and France, followed. Professor Frederick Dupee’s enthusiastic

support helped gain Koch tenure.

He was famous for the ingenuity of his assignments. “My favorite

was to write the first scene of Hamlet, without reading

Hamlet,” David Shapiro ’68 said. “It

showed in how many ways Shakespeare excelled at packing a scene

densely.” For Davey Volner ’04, “the very best

Kenneth Koch assignment was to turn a Wordsworth poem into one by

Wallace Stevens.” Writing a sestina was the choice of Jeffrey

Harrison ’80: “I had never heard of a sestina.”

Justin George Jamail ’02 favored the cut-up: “Write

a poem, cut it up, randomly reposition the lines into a new poem,

and finally compose a third poem inspired by the successes (or failures)

of the first two versions.” This one rang a bell with me,

too. I also liked the collage (write a poem composed of lines lifted

from the books on your shelf), the collaboration (team up with a

classmate and write a poem) and the comic-book opera (mine featured

Archie, Veronica, Betty, Jughead, Moose, Midge and hamburgers).

He was famous for the ingenuity of his assignments. “My favorite

was to write the first scene of Hamlet, without reading

Hamlet,” David Shapiro ’68 said. “It

showed in how many ways Shakespeare excelled at packing a scene

densely.” For Davey Volner ’04, “the very best

Kenneth Koch assignment was to turn a Wordsworth poem into one by

Wallace Stevens.” Writing a sestina was the choice of Jeffrey

Harrison ’80: “I had never heard of a sestina.”

Justin George Jamail ’02 favored the cut-up: “Write

a poem, cut it up, randomly reposition the lines into a new poem,

and finally compose a third poem inspired by the successes (or failures)

of the first two versions.” This one rang a bell with me,

too. I also liked the collage (write a poem composed of lines lifted

from the books on your shelf), the collaboration (team up with a

classmate and write a poem) and the comic-book opera (mine featured

Archie, Veronica, Betty, Jughead, Moose, Midge and hamburgers).