FEATURES

How to Defuse Time Bombs

Quarterback-turned-surgeon Dr. Archie Roberts ’65

screens retired football players for heart disease

By Joshua Robinson ’08

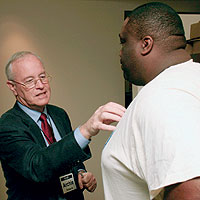

Dr. Archie Roberts ’65 (left)

talks with former Miami Dolphins

football player Keith

Sims at the Living Heart NFL

Players CV Health Program in

January in Miami

PHOTO: AP PHOTO/LUIS M. ALVAREZ

The score was 3–3, time was

running out and the Harvard football fans were turning hostile.

The Crimson had just tied Columbia with a field goal, and Lions

quarterback Archie Roberts ’65 was trying to silence them as he

marched the Light Blue toward the end zone.

As the clock ticked down on that October 1963 afternoon,

Roberts set up Columbia’s chance to win. It was only first or

second down and the Lions already were in position for a long

field goal. The horseshoe stadium in Massachusetts — among

those in attendance was President John F. Kennedy, who had taken the afternoon off to watch his alma mater — grew louder.

This was no time for indecision.

Roberts jogged over to the sideline to consult his coach,

Aldo “Buff” Donelli. “Let’s try one more play from scrimmage,”

Roberts argued. “We’ll throw into the end zone. If I’m

caught, I’ll just throw it away.” Donelli wanted to try the long

field goal right away, but the soft-spoken, deliberate Roberts

convinced his fiery coach otherwise.

Roberts lined up under center, the ball was slapped into his

hand and he dropped into the pocket. But as he cocked his

arm to throw, a hand came up. Suddenly, the wobbly pass was

up for grabs. “As luck would have it, it was intercepted and

that was the end of the game,” Roberts recalls of the tie.

Donnelli chased Roberts across the field and all the way

into the locker room, furious for having been talked into

changing his game plan.

Today, Roberts laughs when he tells that story, but when

the ball fell into Harvard’s hands, it was only funny to the

home fans, and possibly the President. Roberts often wonders “what in the world went through

Kennedy’s mind when he saw this

quarterback running into the locker

room with the coach behind him.”

Some 44 years after throwing

out the playbook against

Harvard, Roberts is the man

writing it, but this time the

objective isn’t the end zone. In 1998,

Roberts, who spent 30 years as a

heart surgeon at hospitals all over

the country after flirting with professional

football, founded the Living

Heart Foundation and has pioneered

advanced, mobile methods

for cardiovascular screening in an

attempt to raise awareness about

heart disease and the special risks for former football players.

Since 2003, the foundation has been sponsored by the National

Football League Players’ Association to conduct screenings of

retired players. In the past four years, Living Heart has screened

more than 1,300 players in 20 NFL cities. But Roberts believes

that they are just beginning to scratch the surface.

“The NFL has been built on a physical prowess and strength

and durability, and the idea of psychological or physical problems

has not been what the NFL has been about,” he says. “Nor has it

been the public’s image of NFL players. They look indestructible,

they look indefatigable, they look immortal. In that setting, it’s

hard to be scrutinizing and looking for defects in the product.”

When Roberts was playing football, there were only a handful

of 300-pounders in the NFL. By 1987, the number was up to

27 players who weighed 300 pounds or more. But as football

has followed the trend to bigger, stronger athletes, that figure

swelled to 240 by 1997; today the number is more than 350. “What doctors are learning is that size is a risk factor for heart

disease, just like hypertension, diabetes or high cholesterol are

risk factors,” Roberts explains.

And, he claims, as players make the transition from the professional

game to retirement, usually in their mid- to late-30s,

those health risks too often are neglected. The widely reported

figure for average life expectancy of an ex-NFL player is 55 — life

expectancy at birth for the average American male is 74.4 years,

according to a 2004 report by the Centers for Disease Control.

“I was aware of the collisions and concussion problems, the

things that the average observer of professional football

would know about,” says Roberts. “I also knew from having

been a player that while the team doctors and the teams delivered

a high level of healthcare for the active players, once the

players transitioned into retirement, there was quite a change.

When you retired, you were on your own.”

During the past year, a number of alarming studies regarding

the long-term effects of concussions on football players

have emerged, and retired professional players have made

public demands for better care from the league. Roberts

asserts the league is taking positive steps toward improving

care for retired athletes. Last July, the NFL and NFL Players’

Association announced the formation of the NFL Cardiovascular

Health Program, to which

Roberts is a consultant.

“Doctors have been thinking

more about short and long-term

consequences of professional football.

The owners, the players’

union and the players have spoken

out about better methods for the

players’ union to help them handle

the disabilities that occur after

football.”

This is Roberts’ way of giving back to the game that made his dream of becoming a doctor a reality.

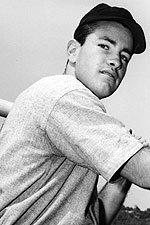

At the College, Roberts lettered

in three sports — though he confesses

he was nothing special on the basketball court — and had the

option to play baseball or football professionally when he graduated.

Ultimately, however, sports wasn’t his long-term plan. “I

loved baseball and I loved football, but I wanted to become a

doctor, and that was the most important thing for me.”

The St. Louis Cardinals selected Roberts, a shortstop who

batted .386 his senior year, in baseball’s first college draft in

1965, while he was drafted in the seventh round by the New

York Jets as a quarterback, and subsequently signed by the

Cleveland Browns.

His numbers made him an obvious candidate for both pro

sports. In football, he played offense and defense, threw for

3,704 career yards, set 17 Columbia and 14 Ivy League records

and was the first quarterback in Columbia history to complete

300 passes. Donelli once said, “Archie Roberts is as fine a

quarterback as I have ever coached, and I believe he is in the

same class as the finest forward passers I have ever seen, men

like Sid Luckman [’39], Y.A. Tittle and Harry Agganis.”

To cap it all off, Roberts also led the Lions in punting.

On the baseball diamond, he set another Columbia record by

batting .371 for his career — that now ranks fourth all-time — and as a senior, Roberts led the nation with 30 RBIs in 21 games.

But it was the Browns who made him an offer he couldn’t

refuse: If Roberts signed with the pro football team, the

Browns would put him through medical school.

“The Columbia family was instrumental in helping to

arrange the opportunity with Case Western Reserve Medical

School and the Cleveland Browns,” he acknowledges. “I

remember in particular, Gene Rossides ’49, a former great running

back for Columbia, was helpful in contacting Art Modell,

who was then the owner of the Browns, and Doug Bond, the

dean of the medical school. Being in Cleveland, they knew one

another and the Browns had provided funding and grants for

the medical school.”

As far as Roberts knows, he is the only person to play professional

football and go to medical school during the season,

balancing his studies and football with remarkable discipline. “Given that both sides, the team and the medical school, were

willing to be flexible and creative and permit an unusual thing

to happen, I was given this opportunity,” he recalls. “It made

it possible in that era. In today’s

world, there’s too much demand

from medical school and football; it

wouldn’t be possible.”

“I was so busy taking care of my patients and teaching

and doing

research that I neglected my own health.”

As he approached the third of

his four years at Case Western

Reserve, Roberts still had not seen

a minute of competitive action for

the Browns. The starting spot

belonged to Frank Ryan, a quarterback

whose claim to fame was having

a Ph.D. in mathematics. Ryan

and Roberts’ best shot at NFL history

then might be as the answer to

a rather obscure trivia question:

“Who was the best educated

starter-backup quarterback tandem

in football?”

By 1967, Roberts thought the opportunity to be a bona fide

NFL quarterback might be passing him by. So when the ewlyformed

Miami Dolphins offered him a chance to start that season,

he jumped at it.

“But guess who was drafted as another quarterback?”

Roberts asks. “Bob Griese.” A future Hall-of-Famer, Griese

went on to play in seven Pro Bowls, win two Super Bowls and

lead the Dolphins through their perfect 17–0 season under legendary

coach Don Shula.

Roberts only played one game and left Miami after a single

season to return to Cleveland and finish his medical degree.

But he has never felt a twinge of regret. “The goal of medicine

was first and foremost. If I had ever been forced to choose, I

would have pursued medicine. I was very lucky to have this

opportunity along the way.”

During nearly 30 years as a cardiothoracic surgeon,

professor of surgery and researcher, Roberts racked

up his most impressive number. He may have

thrown for 3,704 yards in college, but he performed

more than 4,000 open-heart surgeries in the operating theater.

That came to an abrupt end in 1997.

While lecturing a group of cardiologists in New Jersey,

Roberts suffered a stroke. “I’d never been sick a day in my

life,” he explains. “I’d never been in the hospital as a patient

and didn’t have any obvious health issues. I was so busy taking

care of my patients and teaching and doing research that I

neglected my own health.”

In the immediate aftermath, Roberts displayed many of the

characteristic ailments of stroke survivors — trouble with

speech and impaired motor skills on one side of the body. He

could barely move the right arm that carried him through

Columbia to the NFL and finally to medicine. It hit him hard.

“It took me the better part of a year to come to grips with the

fact that I was not immortal and that health issues are unpredictable.

I decided to retire from heart surgery, because it’s a

stressful job with many long hours — probably not what I needed

to be healthy,” Roberts notes.

As he started on the long path to full recovery, he founded

Living Heart, based at Rutgers. The first screenings were

at high schools around Holyoke,

Mass., where he grew up, and the

Columbia football team.

Living Heart rose to prominence,

however, during the massive

rescue efforts following 9-11. A

group of 25 people from the nonprofit

foundation set up on the

Lower East Side and screened more

than 2,000 rescue workers who

were worried about the effects of

their exposure to the debris, smoke

and stress.

“When word got around the city

that someone in the health field

was reaching out,” Roberts remembers, “volunteers poured in from

the hospitals. We had more than

400 at the end of the two-week period … 14 consecutive days,

all day, all night. There’d be rescue workers lined up around

the block in the morning wanting to get in.”

Screening retired NFL players is a change of pace, but the

impact on people’s lives is no different. Roberts continues to

travel throughout the year conducting free screenings sponsored

by the NFL players’ union, as well as a few college football

teams.

With an estimated 18,000 retired players scattered

across the country, many of whom don’t respond to the

union’s invitations for a screening, he knows that cardiovascular

disease will continue to be a silent killer.

“There’s room for much more to be done,” he says. “It’s all a

process, and the league is finding a healthy way of approaching

things.”

Roberts didn’t make it past the fringes of the professional

game, but to many retired players, he may be the best teammate

they never had.

Joshua Robinson ’08 was Spectator’s sports editor in 2006. His

articles have appeared in The New York Times, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and The Washington Post.

|