|

|

|

|

|

FEATURESPeter Nash ’89: Hip-Hop Pioneer, Baseball Historian, FilmmakerBy Jonathan Lemire ’01

Peter Nash 89 (Prime Minister Pete Nice) joined with Michael Berrien (MC Serch) to form the successful and critically acclaimed rap duo 3rd Bass.

Peter Nash ’89 has been a basketball star, Ivy League student, hip-hop pioneer and baseball historian and now is a budding documentary filmmaker. He can rap with hip-hop legends Run-DMC as easily as he can discuss the life stories of 19th-century ballplayers, and, yes, he can see that there does not seem to be much that links the two. Nash’s endless passion is the connection. “It’s a little different, I guess,” says Nash. “But it’s who I am.” Nash learned about rap while playing basketball. He researched long-dead baseball players while touring the world with his seminal rap group. He helped create a film about a legendary Red Sox fan that has now helped inspire another documentary about white artists playing “black” music. “There was no doubt that Pete had always had something else going on in his head. He’s always looking for his next move,” says Michael Berrien, who, as MC Serch, teamed up with Nash then known as Prime Minister Pete Nice in the 1980s to form the successful and critically acclaimed rap duo 3rd Bass. “The guy can do anything he sets his mind to.” Stories about basketball or hip-hop often begin in Brooklyn. So does this one; Nash, who was born in the Greenpoint section of the borough, was introduced to both while spending time with Bishop Ford H.S.’s basketball teams. Nash’s father, Raymond, was athletics director at the Brooklyn school. “I was such a gym rat as a kid, I’d be ballboy on a number of my father’s teams and I’d just hang out with the players,” says Nash. “When the teams would travel, I’d be with them for a week at a time. These were guys from city high schools who were listening to hip-hop that I would not have had access to otherwise. We’d be at Syracuse for a tournament and there I was on the quad, at 10, being taught the Batman dance.’ “Basketball, more than anything, gave me hip-hop.” Nash, who starred in baseball and basketball at Bishop Ford, considered attending the Naval Academy or St. Bonaventure before deciding to enroll at Columbia in 1985. “I knew I wanted to go where I’d get the best education. It came down to academics, yes, and also wanting to stay in New York to pursue rap, even as a hobby.” In high school, Nash had worked on his rhymes as much as his jump shot and slowly gained the acceptance of a hip-hop community that initially didn’t know what to make of a white rapper. But music clubs were not where Nash honed most of his verses it was his Johnson (now Wien) Hall dorm room. “I spent so much of time focusing on my demos,” he says. “I was injured a lot, and didn’t get on the court much, but my paper ankles gave me more time for music.” Nashs junior year began with yet another injury. Asked to red-shirt a season, a choice that would have entailed shelling out another year’s worth of tuition, Nash said no, thanks.

Nash (right) and MC Serch join Flava Flav in Scotland in 1991 during the Public Enemy/3rd Bass European Tour.

In summer 1986, he hosted the first show to play rap music on WKCR. Though it was not renewed at summer’s end, Nash became committed to pursuing a rap career, applying lessons learned from his classes on modern poetry and the Greek classics to his own writings. “I was a struggling college student trying to pay the bills, and my mother wasn’t too thrilled with me pursuing music,” says Nash, an English major. “I was going to be a starving artist forever if I didn’t catch a break.” He caught two: One of his tapes found its way into the hands of Russell Simmons, the legendary founder of Def Jam Records, and he was introduced to MC Serch, a slightly more seasoned rapper. “Friends were telling me, You two should really hook up. You’re going to be competing against each other, so why don’t you join forces?’ ” recalls MC Serch. “When I heard the beat, it was very different from anything I had worked on.” The first song they recorded, “Words of Wisdom,” later became one of the newly-named 3rd Bass’ first hits. Though still unsigned to a record label, they were offered a slot to open for Run-DMC on a tour of Europe, but Nash now known as Prime Minister Pete Nice first had see about breaking a prior commitment. “I had to go to my adviser and ask if I could take a semester off in order to go on a world tour,” he says. 3rd Bass’ first single came out just days after Nash’s graduation and later that year, as they were opening for De La Soul in England, their first album, “The Cactus Album,” began catching fire in the States, selling more than 25,000 copies a week. “For the first time, I knew we could make a living making music,” says MC Serch, who now hosts a show on VH-1 and is involved in several Internet music projects. Showcasing witty lyrics and clever beats, 3rd Bass picked feuds with the Beastie Boys and, most memorably, the much-derided Vanilla Ice, whom they slammed with the song that became their biggest hit, “Pop Goes the Weasel.” As his relationship with Serch grew strained in the wake of their second album, “Derelicts of Dialect,” Nash began to devote himself more to his other love baseball. “I never lost my interest as a baseball fan. When the group toured, I planned for us to see games at places like Wrigley Field [in Chicago] and Fenway Park [in Boston],” Nash said. “He always made sure we hit a memorabilia store. Even in Japan he’d visit old baseball players,” said Serch. The group split up in 1992 and neither artist found much success with his initial solo work. Nash turned his attention to starting a record label, but after it faltered, he devoted himself to baseball full-time. His first step was buying a house in Cooperstown, N.Y., the picturesque community that is home to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Next, he teamed with several partners to develop Cooperstown Dreams Park, a youth baseball facility that soon became home to a national tournament that drew teams from all over the country. Nash then looked toward home for his next project. “As a Bishop Ford freshman I took a walking tour of Green-Wood Cemetery [in Brooklyn] and I remember the teacher telling us that some old ballplayers were buried there,” he said. “I dug in with my research and discovered that a couple hundred of the early baseball figures in Brooklyn, some very important people in the game’s growth between 184070, were all buried there.” The resulting book, Baseball Legends of Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, was published by Arcadia Press in 2003 and the former Pete Nice was suddenly a respected baseball historian. Wanting to give his impressive collection of memorabilia a new home while paying tribute to an oft-overlooked part of the baseball world, Nash set about creating the Baseball Fan Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. The first shrine dedicated to the baseball fanatic, the Hall was to be a homage to Michael McGreevy, a late 19th-century bar owner in Boston who many historians believe was the biggest baseball fan of all. Founder of the Royal Rooters, a club dedicated to the Boston Americans (now Red Sox), McGreevy owned the city’s first sports bar. And Nash couldn’t help but like the bar’s name. “Coincidentally, it was called the Third Base Saloon,” said Nash. “It was the perfect backdrop to the museum we wanted to build.” While painstakingly recreating the ancient bar in Cooperstown, Nash turned his research into another book, Boston’s Royal Rooters. Before the book was published in 2005, it caught the attention of The Dropkick Murphys, a Boston-based Irish punk band that was in the midst of recording a version of “Tessie,” the Royal Rooters theme song that gained new life during the Red Sox’s championship season of 2004.

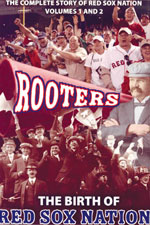

Nash recently completed two years of work on the documentary Rooters: The Birth of Red Sox Nation.

“Originally, we just wanted to use some of his images for the video the Murphys were doing,” says director Ian MacFarland. “But Pete showed up in my apartment with all this crazy memorabilia and it really was clear how important these [early fans] were to Boston’s history.” “About halfway during the meeting I realized where I knew this guy,” says MacFarland. “Prime Minister Pete Nice was in my living room talking baseball!” The music video soon spawned ideas of a full-length documentary, which took nearly two years to assemble. “I’d never met anyone who works as many hours as I do until I met Pete,” says MacFarland, who got his start filming several New England punk bands. “I’d call him at all hours, day or night, and he’d always be working on something.” The documentary, which debuted this summer on the New England Sports Network and was to be released on DVD, may also bring history to life in more ways than one. “The Red Sox have been talking to us about relocating our replica of McGreevy’s Bar to the actual Fenway Park area,” Nash said. “We’ve had some conversations, and while I still want a Fan Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, this may be an opportunity too grand to turn down.” Charles Steinberg, executive vice president/public affairs for the Red Sox, says, “I think it would resonate beautifully in Boston. We’re working on the logistics now, and we want to make it happen whether that is in a year or two. It’s very easy to imagine the 3rd Base Saloon having a new home in the area around Fenway.” Steinberg had nothing but praise for Nash. “While I was among those who was not knowledgeable of his music career, many of the other folks in our office knew him and were thrilled. When I introduced them, they started rapping his lyrics back to him!” Last year, Nash and his wife, Roxanne, welcomed their first child, William. And, as the family shuttles between upstate New York and Long Island, Nash is both putting the finishing touches on Rooters: The Birth of Red Sox Nation and starting to work on his next project: a documentary on the white appropriation of black music, told through the eyes of white MCs. Its title is The White Negro. He is also working on a biography of early baseball writer Henry Chadwick and his contributions to the sport, including many rare, vintage images from the Chadwick Collection, of which he is owner and curator. “In strange ways, it seems that everything I do is sort of connected,” says Nash. “These are all things that I’ve long been interested in.” Jonathan Lemire ’01 is a staff writer for The New York Daily News, a frequent contributor to CCT and a loyal member of Red Sox Nation.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||