|

|

|

|

|

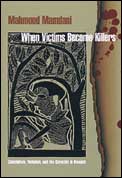

COLUMBIA FORUM The Rwandan genocide was one of the most horrific events of the late 20th century. From March to July 1994, between 500,000 and one million of the Tutsi minority were killed by members of the Hutu majority, who also killed as many as 50,000 fellow Hutu who refused to participate in the genocide. What is most troubling is that the massacres were the work of ordinary people, who so easily heeded calls to kill. The genocide "was carried out by hundreds of thousands, perhaps even more, and witnessed by millions," says Mahmood Mamdani, Herbert Lehman Professor of Government and director of Columbia's Institute of African Studies. In this excerpt from When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda (Princeton University Press, $29.95), an attempt to understand the dynamics behind the slaughter, Mamdani explores the differences between settlers' and natives' genocide.

Accounts of the genocide, whether academic or popular, suffer from three silences. The first concerns the history of genocide: many write as if genocide has no history and as if the Rwandan genocide had no precedent, even in this century replete with political violence. The Rwandan genocide thus appears as an anthropological oddity. For Africans, it turns into a Rwandan oddity; and for non-Africans, the aberration is Africa. For both, the temptation is to dismiss Rwanda as exceptional. The second silence concerns the agency of the genocide: academic writings, in particular, have highlighted the design from above in a one-sided manner. They hesitate to acknowledge, much less explain, the participation — even initiative — from below. When political analysis presents the genocide as exclusively a state project and ignores its subaltern and "popular" character, it tends to reduce the violence to a set of meaningless outbursts, ritualistic and bizarre, like some ancient primordial twitch come to life. The third silence concerns the geography of the genocide. Since the genocide happened within the boundaries of Rwanda, there is a widespread tendency to assume that it must also be an outcome of processes that unfolded within the same boundaries. A focus confined to Rwandan state boundaries inevitably translates into a silence about regional processes that fed the dynamic leading to the genocide. We may agree that genocidal violence cannot be understood as rational; yet, we need to understand it as thinkable. Rather than run away from it, we need to realize that it is the "popularity" of the genocide that is its uniquely troubling aspect. In its social aspect, Hutu/Tutsi violence in the Rwandan genocide invites comparison with Hindu/Muslim violence at the time of the partition of colonial India. Neither can be explained as simply a state project. One shudders to put the words "popular" and "genocide" together, therefore I put "popularity" in quotation marks. And yet, one needs to explain the large-scale civilian involvement in the genocide. To do so is to contextualize it, to understand the logic of its development. My main objective in writing this book is to make the popular agency in the Rwandan genocide thinkable. To do so, I try to create a synthesis between history, geography, and politics. Instead of taking geography as a constant, as when one writes the history of a given geography, I let the thematic inquiry define its geographical scope at every step, even if this means shifting the geographical context from one historical period to another. By taking seriously the historical backdrop to political events, I hope to historicize both political choices and those who made these choices. If it is true that the choices were made from a historically limited menu, it is also the case that the identity of agents who made these choices was also forged within historically specific institutions. To benefit from a historically informed insight is not the same as to lapse into a politically irresponsible historicism. To explore the relationship between history and politics is to problematize the relationship between the historical legacy of colonialism and postcolonial politics. To those who think that I am thereby trying to have my cake while eating it too, I can only point out that it is not possible to define the scope — and not just the limits — of action without taking into account historical legacies. The genocidal impulse to eliminate an enemy may indeed be as old as organized power. Thus, God instructed his Old Testament disciples through Moses, saying:

If the genocidal impulse is as old as the organization of power, one may be tempted to think that all that has changed through history is the technology of genocide. Yet, it is not simply the technology of genocide that has changed through history, but surely also how that impulse is organized and its target defined. Before you can try and eliminate an enemy, you must first define that enemy. The definition of the political self and the political other has varied through history. The history of that variation is the history of political identities, be these religious, national, racial, or otherwise. I argue that the Rwandan genocide needs to be thought through within the logic of colonialism. The horror of colonialism led to two types of genocidal impulses. The first was the genocide of the native by the settler. It became a reality where the violence of colonial pacification took on extreme proportions. The second was the native impulse to eliminate the settler. Whereas the former was obviously despicable, the latter was not. The very political character of native violence made it difficult to think of it as an impulse to genocide. Because it was derivative of settler violence, the natives' violence appeared less of an outright aggression and more a self-defense in the face of continuing aggression. Faced with the violent denial of his humanity by the settler, the native's violence began as a counter to violence. It even seemed more like the affirmation of the native's humanity than the brutal extinction of life that it came to be. When the native killed the settler, it was violence by yesterday's victims. More of a culmination of anticolonial resistance than a direct assault on life and freedom, this violence of victims-turned-perpetrators always provoked a greater moral ambiguity than did the settlers' violence. More than any other, two political theorists, Hannah Arendt and Frantz Fanon, have tried to think through these twin horrors of colonialism. We shall later see that when Hannah Arendt set out to understand the Nazi Holocaust, she put it in the context of a history of one kind of genocide: the settlers' genocide of the native. When Frantz Fanon came face-to-face with native violence, he understood its logic as that of an eye for an eye, a response to a prior violence, and not an invitation to fresh violence. It was for Fanon the violence to end violence, more like a utopian wish to close the chapter on colonial violence in the hope of heralding a new humanism. From When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda by Mahmood Mamdani. Copyright © 2001 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by arrangement with Princeton University Press.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||