If you know of a Columbia College student, faculty member, alumnus/alumna or program we should spotlight, or if you would like to submit a story, please contact:

Columbia College

Office of Communications

cc-comms@columbia.edu

“For the project, we were united in our interest in nuclear issues, an interest that grew in part from our experiences in Frontiers of Science.” — Asha Banerjee CC’17

Asha Banerjee CC’17, along with the K-1 Project (now the Center for Nuclear Studies at Columbia University), spent seven days in the Marshall Islands in the summer of 2014. While there, she, along with two classmates and Physics Professor Emlyn Hughes, created a short documentary on nuclear proliferation. Below, Asha reflects on her research and her experience.

Peering down from the airplane window, the pulsating blue of the Pacific Ocean seemed endless. Millions of square miles of turquoise canvas unfolded before any land came into sight, the sun beaming forcefully like a laser, down onto the ocean. It was August 14, 2014, and I, along with Physics Professor Emlyn Hughes, Autumn Bordner CC’14 and Danielle Crosswell CC’17, was on my way to the Marshall Islands, a series of 29 atolls sprawled across the Northern Pacific.

The Marshall Islands as seen from the airplane. Photo: Asha Banerjee CC’17

The Marshall Islands as seen from the airplane. Photo: Asha Banerjee CC’17

The atolls of the Marshall Islands, skinny crescent-shaped pieces of land, are surrounded by vibrant coral reefs submerged in the ocean. Many of the green, sandy atolls just barely connect to the next ones; others are tens and hundreds of miles away, separated by swathes of ocean. From space, the link of atolls resembles a string of pearls, leading to the nickname “The Pearl of the Pacific.” But, the geographic beauty and tranquility of the Islands are marred by the memory of the yellow-orange explosions of the past, the burden of a nuclear legacy that did not end with the culmination of World War II. Almost 70 years after the end of the war, we were on our way to those same islands to film a short documentary about nuclear proliferation as part of the K-1 Project.

The K-1 Project, now the Center for Nuclear Studies at Columbia University, was started in 2011 by Professor Hughes and his wife, Ivana Hughes, lecturer in the discipline of chemistry, to bring awareness about nuclear issues — including proliferation, energy, and security — and to start a discussion about the future of nuclear issues, especially amongst students and young people. Professor Hughes saw film as a medium for reaching out to students across America about these issues and so, for the last three summers, he has hired students who have finished their Frontiers of Science Core course to create films — as well as other materials — about nuclear issues. Two creative films, an animated film and two documentaries about various nuclear issues have been created since 2011.

Asha Banerjee CC’17 drinking coconut water in its shell at the Tide Table Restaurant in Hotel Robert Reimers, Majuro Atoll. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

Asha Banerjee CC’17 drinking coconut water in its shell at the Tide Table Restaurant in Hotel Robert Reimers, Majuro Atoll. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

Last summer, our task was to create a third short documentary about nuclear proliferation. We began the summer in Palo Alto, California, interviewing experts near Stanford and in the Bay Area. Autumn, Danielle and I all come from different academic interests and majors: Autumn is an environmental science major and statistics and sustainable development minor who had been part of the project for two summers; Danielle is a computer science major with a background and passion for theater; and I am a history and economics major with a background in speech and debate. Yet for the project, we were united in our interest in nuclear issues, an interest that grew in part from our experiences in Frontiers of Science.

Early in the summer, as we pored over news articles and historical archives, we found ourselves drawn to the tragic history of the Marshall Islands and its current battle in the courtroom against the United States and the other nuclear powers of the world. A few weeks later, to truly understand the issue and the people, we decided to go to the Marshall Islands to conduct interviews with government officials and citizens.

According to our research and interviews, starting in 1946, the United States tested 67 thermonuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands, at the Bikini and Enewetok Atolls. The largest test, called Castle Bravo and conducted in 1954 at Bikini Atoll, was the first deliverable high-yield thermonuclear device ever tested by the United States. Castle Bravo had a yield of 15 megatons of TNT, 1000 times higher than “Little Boy,” the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. The destruction was catastrophic. At least four inhabited atolls — Enewetok, Rongelap, Uterik and Bikini — were severely contaminated, with the nuclear fallout spread over 7,000 square miles. Senator Jeban Riklon, one of the government officials we interviewed, recalled that the heat of the wind burned skin off human beings and the rest of their skin was so itchy that people would scratch till they bled. In other nuclear tests, white powder fell from the sky and inhabitants ate it and played in it, not knowing what had happened and thinking it was snow.

The scientists and servicemen working on the project said they had miscalculated the fallout range and wind patterns. However, many people on the Marshall Islands, like Limowe, a woman we interviewed who was a child at the time of the testing, believes that the scientists deliberately ignored weather forecasts and predictions in order to carry out the test. Radiation sickness, including various types of cancer and thyroid problems, spread amongst the exposed population over the next few years. Parts of the islands, notably Rongelap Atoll, remain uninhabited because of the contamination.

Professor Emlyn Hughes, Asha Banerjee CC’17, Danielle Crosswell CC’17 and Autumn Bordner CC’14 with Minister of Public Works and Uterik Atoll Senator Hiroshi Yamamura and members of his family, wearing gifts of local Marshall Islands jewelry. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

Professor Emlyn Hughes, Asha Banerjee CC’17, Danielle Crosswell CC’17 and Autumn Bordner CC’14 with Minister of Public Works and Uterik Atoll Senator Hiroshi Yamamura and members of his family, wearing gifts of local Marshall Islands jewelry. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

For our documentary, we spent six days on Majuro Atoll, a curving island just under four square miles, with one main road. The view from both sides of such a tiny strip of land is the vast ocean, and when looking out from the island, I had a feeling of total and complete isolation. We stayed at the Hotel Robert Reimer, where most of our fellow guests were tourists from Australia and New Zealand who were visiting to take advantage of the excellent fishing, and members of the U.S. Coast Guard.

Our days were filled with videotaping and conducting interviews of government officials and citizens who remembered the testing, as well as Thomas Armbruster, the current U.S. ambassador to the Marshall Islands. We interviewed as a group of three, with Autumn working the camera, Danielle doing sound and me asking the questions. Some days we had as many as five interviews. The stories, sights and sounds were so mesmerizing that though we returned to the hotel tired each day, we were satisfied. In the evenings, we often ate in the hotel’s restaurant, the Tide Table Restaurant, where many Majuro locals came to eat. The food was mostly Western and American — burgers, sandwiches and pasta — but we also tried a few local foods, including delicious fresh tuna, reef fish breadfruit (a starchy fruit best eaten as a fried chip) and papaya.

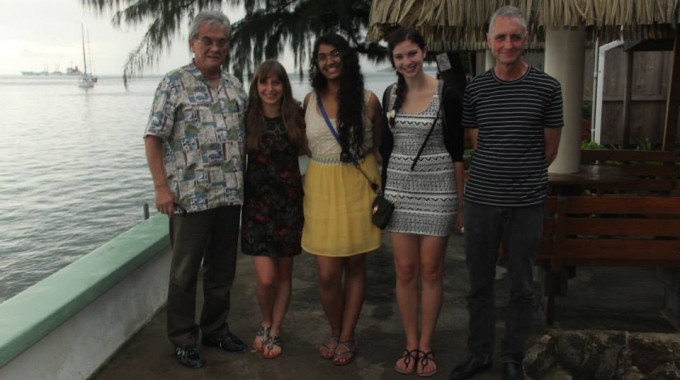

Asha Banerjee CC’17, Professor Emlyn Hughes, Danielle Crosswell CC’17 and Autumn Bordner CC’14 at the airport. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

Through our interviews, we discovered two incredibly different sides to the nuclear issue. The Marshallese describe the United States Department of Energy (formerly known as the Atomic Energy Commission) as consisting of insensitive, uncaring scientists who saw an opportunity to learn about the human impact of radiation from a small, isolated population of the world. The American Embassy (and government by proxy) maintains that Castle Bravo was an accident and that medical care and compensation were given fully and effectively. Citizens who remember the testing were angry and resentful at the thought that a powerful country like the United States might have carried out such atrocious deeds on an innocent country and people. But we also witnessed appreciation for and trust in the powerful military and humanitarian relationship that still exists between the Marshall Islands and the United States.

Asha Banerjee CC’17, Professor Emlyn Hughes, Danielle Crosswell CC’17 and Autumn Bordner CC’14 at the airport. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

Through our interviews, we discovered two incredibly different sides to the nuclear issue. The Marshallese describe the United States Department of Energy (formerly known as the Atomic Energy Commission) as consisting of insensitive, uncaring scientists who saw an opportunity to learn about the human impact of radiation from a small, isolated population of the world. The American Embassy (and government by proxy) maintains that Castle Bravo was an accident and that medical care and compensation were given fully and effectively. Citizens who remember the testing were angry and resentful at the thought that a powerful country like the United States might have carried out such atrocious deeds on an innocent country and people. But we also witnessed appreciation for and trust in the powerful military and humanitarian relationship that still exists between the Marshall Islands and the United States.

Today, the U.S. and the Marshall Islands have a deeply intertwined and complicated political relationship. In 1986, the Republic of the Marshall Islands entered a Compact of Free Association with the United States, which granted sovereignty to the Marshall Islands in exchange for the lease of Kwajalein Atoll as a military base. Though recognizing and maintaining this friendly relationship, in April 2014, the Marshall Islands filed two lawsuits against the United States and its allies to foster awareness about nuclear issues and to compel these countries to rethink their nuclear programs. One, filed through the International Criminal Court of Justice in The Hague, Netherlands, is directed against the nine states that have nuclear weapons: U.S., U.K., France, Russia, China, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea. The second, filed through the District Court of the Northern District of California in San Francisco, is directed towards the U.S. alone.

Asha Banerjee CC’17 on the beach on Majuro Atoll. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

Asha Banerjee CC’17 on the beach on Majuro Atoll. Photo: Courtesy Asha Banerjee CC’17

Both lawsuits allege that the nine countries with nuclear weaponry are not in compliance with Article VI of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, signed in 1970. As of 2011, 189 countries were parties of the Treaty. Article VI states that countries must “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament.” The Marshall Islands lawsuits contend that since these countries are continuing to improve and sustain nuclear weapons, they are out of compliance with the Treaty. Regardless of the outcome, these lawsuits have propelled the debate on nonproliferation and nuclear weapons back to the forefront of public discussion.

Seven days after we arrived, we left the Marshall Islands. After the plane took off from the skinny atoll, I looked down at the green shores, watching them vanish into the dark, deep Pacific. After numerous interviews and conversations, I feared that the island’s geographic isolation would allow an entire culture, people, and nuclear legacy to get swallowed up in the Pacific. Yet I also felt hope as we arrived home. I remembered the “Nitijela,” as the opening of Parliament is called in the Marshall Islands — a highlight of my trip. Watching the government officials wearing ceremonial flower garlands and hearing children’s choir groups sing the National Anthem, I felt a sense of unity and solidarity amongst the people of the various atolls as they came together as citizens of the Marshall Islands.

With the domestic lawsuit against the United States for violation of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Marshall Islands has compelled the United States to answer again for the past, and has reopened the debate on nuclear proliferation. Hopefully, the conversation about nuclear issues and consequences will spread among the public and youth across the world, as students, policymakers and scientists seriously discuss the ramifications and future of nuclear weapons, and look to the history of the Marshall Islands for lessons. Quiet everyone, the court is now in session.

Asha Banerjee CC’17 is double majoring in history and economics. She is a managing editor and web columnist for the Columbia Political Review, where she covers international events and world leaders.