Two alumnae break ground on a groundbreaking San Francisco museum.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Two alumnae break ground on a groundbreaking San Francisco museum.

Alison Gass ’98

KATY PRITCHARD

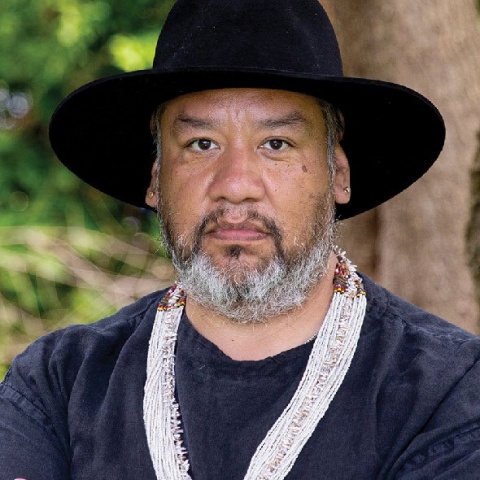

Jonna Hunter GSAPP’96

ULYSSES ORTEGA

With decades of curatorial and development experience between them — Gass’ résumé includes the Jewish Museum and SF MoMA; Hunter’s, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History — the Bay Area alumnae had the idea to create a radically innovative, non-collecting contemporary art museum from the ground up. One that could respond quickly to current events, take ambitious risks and prioritize inclusivity and accessibility; a museum made distinctive for having “social justice as part of its DNA,” Gass says.

Astonishingly, Gass and Hunter turned their dream institution into an actual, 11,000-square-foot museum in just over a year. On October 1, the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco will open to the public in the city’s artsy-industrial Dogpatch neighborhood, free of charge, under the leadership of Gass as the Krieger Family Director and Hunter as deputy director.

Their of-the-moment vision quickly found support from local investors, especially those in the tech industry. “We put our pitch together as: ‘What if you had the privilege to start an institution, coming out of 2020 and 2021?’” Gass says. “We recognized that museums are facing a bit of a crisis around issues of equity and we don’t have all the answers, but we’re willing to recognize some of the problems and say that museums need a bit of course correction.”

Gass and Hunter have ambitious goals: They are working to forge a more transparent business model and promote a more diverse art history canon, as well as revamping how art is curated, how artists and staff are compensated, and how art spaces are accessed.

In this complicated city that’s renowned for both its liberal ideals and its profound income disparity, ICA SF seems like exactly the right place to happen at the exact right time. “I think that there are shifts that can happen,” Gass says. “And somehow, things like the ICA are evidence of the fact that extreme wealth and extreme progressive values can come together to make impact happen.”

Being a non-collecting museum — in other words, not owning a permanent artwork collection — gives an institution a lot of freedom. For one thing, storing and maintaining the work is expensive; on top of that, it doesn’t stay contemporary for very long. Most significantly, it can limit a curator’s vision, because a museum has a responsibility to show and tell stories about the work that it owns.

“If you don’t have a collection, it’s easier to say, ‘Oh my god, we’ve just lived through a global pandemic — or as another example, the racial reckoning after George Floyd’s murder — and I want to tell that story,” Gass says. “And I don’t have to look in the basement to do that. I can look at the world around me and decide I want that artist to tell that story.”

Gass, who is from Boston but had been living in the Bay Area since 2005, left the West Coast in 2017 to lead the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago; she returned to California three years later, in the middle of the pandemic, to head the Institute of Contemporary Art San José. ICA SJ’s non-collecting mission was appealing — and ultimately, inspiring.

“I came to believe that the most impactful work I could do was in small, nimble, non-collecting museums,” Gass says. “Places that can respond quickly in the moment to things that are happening in the world, and that are able to find the artists who can shed light on what’s going on.”

“It’s critical to us that everyone who walks through the doors feels welcome, feels comfortable,” Gass says

Gass feels that this type of institution is an important part of the art world ecosystem; it’s a popular style of museum in Europe, known there as a kunsthalle. And San Francisco, though it does have many excellent art institutions and galleries, didn’t have one.

Excited about the idea of creating a San Francisco kunsthalle, Gass spoke to collectors and supporters, then reached out to her friend and former colleague Hunter and told her this was something they should try. “This is a story that maybe could only happen in a place like San Francisco, because there’s this mindset of experimentation and risk taking here,” she says.

Gass and Hunter were put in touch with Andy Rappaport, a venture capitalist who, with his wife, Deborah, founded the Minnesota Street Project, which develops Dogpatch art spaces. Rappaport encouraged them to consider the new museum project as a startup; he then put up a million dollars and helped Gass and Hunter secure a lease for the building. All they had to do was raise a matching million.

It took them just six weeks. Within eight months, they had $5 million in pledges.

“That told us this idea was resonant, that this was something this community wanted to see happen,” Gass says. “There were a couple of really key people — some big tech names and some big art names.” (Her position was underwritten by Mike and Kaitlyn Krieger; he is the founder of Instagram.)

Gass and Hunter believe it’s important to talk about the business of museums — not just the exhibitions — with their donors and museum staff. And the reality is that in order to keep the museum free to the public, its entire revenue stream has to come through giving. They are currently making decisions about whether (and how) to solicit donations from museum guests, while taking care to make sure no one feels uncomfortable about not contributing.

“It’s critical to us that everyone who walks through the doors feels welcome, feels comfortable,” Gass says. “There is a deep barrier for a lot of people to just crossing the threshold of a contemporary art museum — many people feel that it’s not a place for them. It’s a big mission for us to address that and begin to change it.”

Artist Jeffrey Gibson is creating “a meditation on land acknowledgement” for ICA

SF’s opening.

BRIAN BARLOW

BRYAN McDANIELS

Guest curators Tahirah Rasheed and Autumn Breon

DA’SHAUNAE MARISA

“These are two very different shows,” she continues, “and the choice to go to a guest curator model is evidence of us being aware of the need to get intersectional voices into museums.” Moving forward, ICA SF will feature a mix of California and Bay Area artists as well as those who are more globally recognized. “The Bay Area is a hard place to be a working artist,” Gass says. “So we want to make sure we’re creating opportunities for them.”

An artist- and community-centered museum would not be fully walking the walk if it didn’t also consider equity for staff, and Gass and Hunter are grappling with how to build a better future for museum workers. Low pay in the field and the expectation of a graduate degree are barriers to many; Gass says they specifically took educational requirements and years of specific museum experience off their job descriptions. “We know that we have to set salaries fairly and that we have to focus on pipeline course correction; that may be through paid internships and creating opportunities for our senior people to have the bandwidth for mentorships,” she says.

At the moment, ICA SF has a staff of six, with some additional freelance consultants. “That’s not ‘normal’ for the museum world,” Gass says. “But it’s constantly changing — and that gets back to that mentality of us being a startup. We’re all still figuring it out.”

Both women say that their experience at Columbia was foundational. In fact, in many interviews Gass attributes a single class — “Women in Visual Culture in 19th Century Paris,” taught by Marni Kessler — to starting her on her career path. “Art history became my everything,” Gass says. “I even petitioned to take extra classes.” Two especially memorable professors were Jonathan Crary ’72, GSAS’87 and Rosalind Krauss; Krauss remained an important figure for Gass while she earned an M.F.A. at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts.

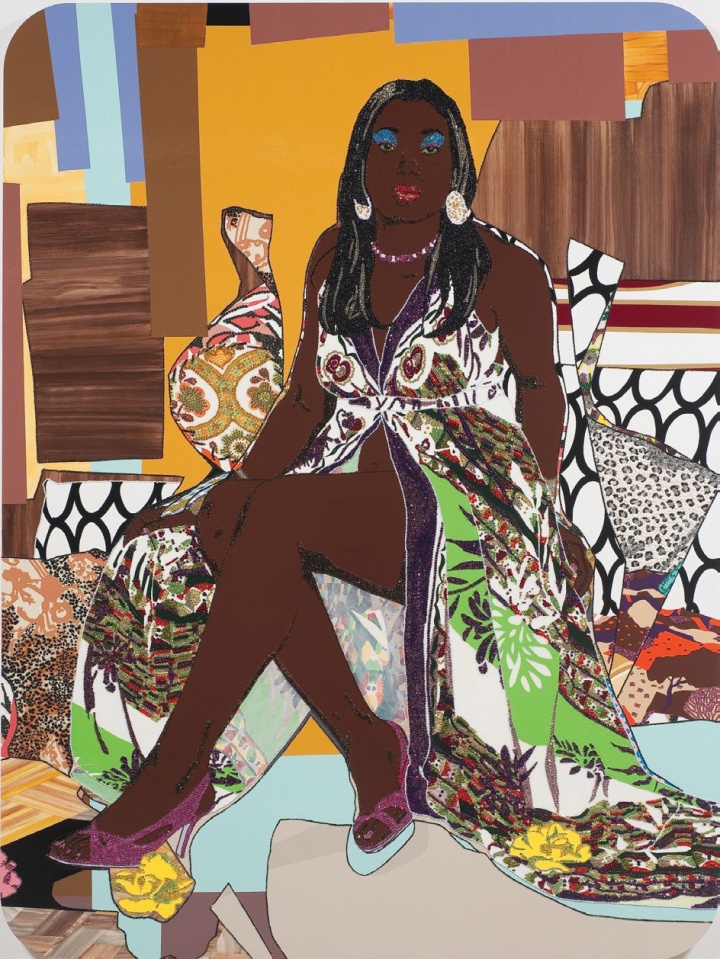

Mickalene Thomas’ 2010 painting, Love’s Been Good to Me #2, will be featured in the museum’s front gallery.

COURTESY THE DAUBER/LEVIN COLLECTION

Hunter’s time at the Architecture School was equally influential. “I was drawn to the built world and to design; learning how architecture and thoughtful development can change neighborhoods really stuck with me,” she says. “And now that translates to: ‘How can a museum impact a community?’”

Gass and Hunter met when both were part of the senior leadership team of the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford, and both say their work at university museums was instructive. “I grew up in rural Oregon, and I never went to an art museum before college,” Hunter says. “I think there’s a tremendous opportunity to see the world through a different lens that a university art museum can have.”

Gass adds that as a curator at both Stanford and Chicago, she relished having access to thinkers from every university department, and she is excited about bringing that interdisciplinary approach to ICA SF. For the Gibson exhibit, the curators are looking at partnering with the Ramaytush Ohlone tribe of Northern California, as well as with climatologists, to see what they can learn about the earth. “And we also want to get some input about economics, because Dogpatch has changed dramatically from a super-industrial area to a wealthy one because of its proximity to Silicon Valley,” she says.

Despite the local affluence, ICA SF won’t look that fancy on its opening day. Gass says that for timing and budget reasons, when the museum launches in September it will still look a little scrappy. “Sort of like a found building with art in it,” she says with a laugh.

“We started out so fast, like a rocket, but so much of what Jonna and I know about museums hasn’t even begun to be put to use yet,” Gass adds. “We remind ourselves all the time that this does not have to spring fully formed from the head of Zeus.

“Those of us in 2022 don’t have a lot of cultural reference for museums starting, but we’re doing it,” Gass continues. “So I think there are some lessons that we’d like to hold on to and take with us as we move into being a museum that lives and breathes.” And evolves. Because in order to remain the most contemporary contemporary art institution, ICA SF must be, as Gass says, “always under construction.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu