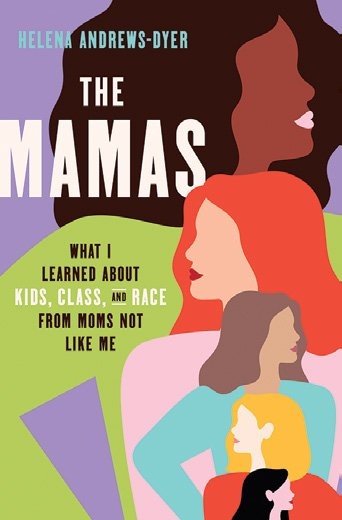

Journalist Helena Andrews-Dyer ’02 explores questions of motherhood, race and identity.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Journalist Helena Andrews-Dyer ’02 explores questions of motherhood, race and identity.

JARED SOARES

Soon Andrews-Dyer was immersed in a world of baby music classes and ill-advised kid comparing, marathon text chains and the subtext that went with them. “I was always thinking, what does this say about the larger question of motherhood, or belonging and identity?” she says. “All of these things were swirling in my head.”

Pregnant with Sally when President Trump was elected, Andrews-Dyer also had to face “the implications of raising a Black child in a world that had no qualms about wearing its racism on its sleeve.” Four years later, the swirl of questions and concerns had only heightened against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic and George Floyd’s murder. Then Andrews-Dyer’s second daughter, Robyn, was born. Taking it all in, she realized she could turn her takes on purportedly post-racial parenting into a more layered account.

The result is The Mamas: What I Learned About Kids, Class, and Race from Moms Not Like Me (Crown, $27). “Telling the story of motherhood from a Black woman’s perspective is something that doesn’t happen often enough,” says Andrews-Dyer, who is also a Washington Post reporter. “So just doing that was big in and of itself. But then I thought, let me put on my journalist hat and really dive deeper.”

“The Mamas” of the title refers to several mom groups, the first and largest of which introduces her to the pleasures of conditional companionship, when “there is only one character trait that really matters — your tiny human proxy.” But her joy at finding a space to connect is quickly tempered as she encounters ignorance and assumptive thinking. In one instance, the clocking of infant milestones — a common new parent pastime — becomes shot through with racist implications when one mom says to Andrews-Dyer, “Remember, you can’t compare them.” Later, Andrews-Dyer becomes indignant when, following the group’s “BLM awakening,” a mom creates a multi-tab spreadsheet of children’s books with Black people in them. Andrews-Dyer sifts through her reactions: Was the spreadsheet ridiculous and performative? Better than nothing? Then, realizing that of 41 recommendations she owns just two, she turns her aim on herself: “Two! What did that say about me? How down was I, really?”

This internal conflict, the circumstances that ignite it and the questions it raises for Andrews-Dyer about her identity, give the book its drive. “Good memoir is about making yourself feel uncomfortable about the things you’ve dug into and discovered about your- self,” she says.

She is also adept at making sense of her experiences in larger context, exploring topics like intensive mothering and school lottery systems, and how both intersect with class and race. She dedicates an entire chapter to the history of her Bloomingdale neighborhood, where racist restrictions on home buying were at one time literally written into the property deeds.

Andrews-Dyer’s voice is a powerful instrument: She is fiercely honest, self-deprecating and funny as hell; she never shies from leaning into contradiction. She recalls how College writing professor Victor LaValle SOA’98 was the first to see her authentic self emerging on the page and encouraged her to keep going. (She majored in English literature with a concentration in creative writing.) After graduation, she did stints in New York City’s magazine world before earning a master’s in journalism from Northwestern and shifting to newspapers.

Andrews-Dyer says she hopes her story will validate other people’s experiences, as well as promote conversation between mothers of different backgrounds, “whatever those be — different racial backgrounds, socioeconomic backgrounds, the married mom versus the single mom.” Motherhood can provide powerful community, she adds, but “we sometimes assume, ‘well, we’re all moms, we’re all struggling in the same way or thriving in the same way.’ And that’s not true. It’s important to understand that we are not all coming from the same place and we didn’t get here the same way.”

In this excerpt, Andrews-Dyer finds herself in a moment of peak stress and exhaustion, contemplating her relationship to a small group of women she’d become closer with, the self-styled “Super Cool Moms.” In embracing the outlet that their company provides, she can’t help but ask what it means about herself.

— Alexis Boncy SOA’11

It had stressed me out so much that my thyroid, an organ (?) I previously wasn’t sure I even had, was basically telling me, “Bitch, you need to pump the brakes.” Add to that mental breakdowns, Covid, pneumonia. Girl, if anyone needed an Rx for a chill pill, it was me. Instead of running myself ragged about what kind of mother I was, why not just admit there was no blueprint? I was becoming whatever mother, whatever person, I was supposed to be. Your authentic self doesn’t arrive via stork, you have to search it out yourself.

Once, the godmother of Becoming and mom-in-chiefing, the Michelle Obama, personally gave me some advice that I promptly ignored.

This was right before Rob and I got married. I was covering a fancy-pants event at a super-swank house in Washington. My plan was to get in, take some notes, and then get out with enough time to watch an Angel rerun. When I got wanded by Secret Service in the garage I figured maybe Valerie Jarrett was there, or even Second Lady Jill Biden, whom I’d met before. That is not a humblebrag, promise. Once I got inside and had a glass of champagne, the gorgeous and tall Black woman with the perfect bounce to her hair didn’t immediately register as the woman whose entire existence served as my vision board. I just thought, I have to ask that lady where she got that haircut. And that dress. And that nail color. And that general aura of amazingness.

“Can you believe she came,” whispered my friend Aba, who sidled up to me with her iPhone already in camera mode.

“Who?” I was still feverishly taking notes in my own phone and barely looking up.

“The First Lady, girl!”

I played it cool for the next hour and a half, because who wants to be the yokel who gets gunned down while attempting to hug Michelle Obama? The plan was to look normal by taking more notes, while secretly recording everything Mrs. Obama did. 8:20: FLOTUS laughs like a human being. 8:22: FLOTUS’s arms are not a myth. 8:27: FLOTUS continues to walk on earth and has yet to ascend to the heavens. And so on.

It was Aba who made me actually talk to her. I was trying to blend in near a sofa, ready to sneak a picture for her, when I looked up and was suddenly being introduced.

“... and this is Helena Andrews,” Aba said, graciously pulling me into the conversation.

“You look familiar,” said the First Freaking Lady of these United States to yours truly. “I think we’ve met before.”

After recovering from a mild seizure, I managed to say something like, “Ah, no, um, I don’t think so. I write for The Post so maybe ... ”

She looked suspicious when I mentioned I was a reporter (damn it!), but her smile came back almost immediately. She then rubbed my arm, which I immediately vowed to smell later. The only thing I could think to ask her about was my impending marriage. I figured whatever advice she gave me would last a lifetime; plus if anything went wrong, I could always say, “Well, Michelle Obama made me do it” and all would be forgiven.

“Hmmm, that’s a longer conversation over cocktails,” said Mrs. Obama (if she had invited me to cosmos on my actual wedding day, I would have canceled the whole damn thing). “But most important, make sure you’re always your authentic self. If you try too hard to be someone you’re not, it won’t work. That’s what’s sustained Barack and I for all these years.”

I nodded like an idiot and listened more as she told me not to “trip on the wedding” even if one of my girlfriends showed up in the wrong thing. “It’s just one day.”

What stuck was her commandment to be my authentic self. This was a direct command from the forever First Lady. To ignore it would be treason. But just who the heck was she, my authentic self, that is? I noodled the question for years after that night. In the years since, I’d become a wife and a mother. I was a daughter and friend. Did I know exactly what those versions of me looked like or had the mugshots changed over time? Perhaps all the exhaustive work I was doing to raise perfect children and be the perfect mother was just another way to hide that authentic self, to bury her under expectations that didn’t matter to anyone, not even me when I really thought about it. If that was the case then the Mamas, the Super Cool Moms, all of them, weren’t women to necessarily emulate or even be embarrassed by. We held up mirrors to each other even if the reflections weren’t always the same.

Maya Angelou once said, “We have to confront ourselves.” Me, myself, and I were due for a face-to-face-to-face. What I realized eventually is that the fantasy that fueled my twenties? I’d needed that. We all do. I needed to feel like the invincible heroine in a silk headscarf fighting off evil questions about why I hadn’t found a man. As the years stacked up, I had dreamt up another fantasy to pull me through the next decade. This one filled with babies and momming so hard. And now that picture needed some serious retouching, somehow reconciling it with the old ones. To really confront who I was as a mother, a Black mother, I’d have to give birth yet again. The emotional labor pains were the worst but my authentic self was in there somewhere.

From the book THE MAMAS: What I Learned About Kids, Class, and Race from Moms Not Like Me by Helena Andrews-Dyer. Copyright © 2022 by Helena Andrews-Dyer. Published by arrangement with Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu