The Roger Lehecka Double Discovery Center celebrates 60 years of helping students realize their greatest potential.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

The Roger Lehecka Double Discovery Center celebrates 60 years of helping students realize their greatest potential.

Students assembled on Low Plaza to create this photo in honor of the program’s name change to Double Discovery Center.

COURTESY THE ROGER LEHECKA DOUBLE DISCOVERY CENTER

In his first days as a College student in 1963, during a welcome address by Dean David B. Truman, Roger Lehecka ’67, GSAS’74 received a message that would change his life.

“Truman said, ‘Every one of you is privileged to be here, and that puts an obligation on you to share that privilege in some way with others who do not have it,’” Lehecka recalls. “Now, my family was very poor, I grew up in public housing — so hearing him say I was privileged was a little bizarre. But the obligation part stuck with me. And then because of the enthusiasm the College had for service, things happened. We did things.”

In fact, that message would ultimately change thousands of lives. Encouraged to donate their time and energy, Lehecka and a cohort of scrappy undergrad volunteers launched a project that now bears his name, and is still having an impact six decades later. The Roger Lehecka Double Discovery Center — a pioneering education program for underserved youth that has also become one of Columbia’s signature initiatives — celebrates its 60th anniversary this year. Co-founded by Lehecka in 1965, DDC provides first-generation, low-income New York City high schoolers with resources and support to improve their experience of learning and imagine a different future for themselves.

Over the years, DDC has made college a reality for more than 25,000 teens; 90 percent of high school seniors participating in DDC programs graduate from high school on time and enter college the following fall.

But beyond the longevity, the impressive data points and the accolades — DDC even got a shoutout from President Bill Clinton in 1998 — perhaps its greatest measure of success is the direct effect it has had on the young lives of its alumni.

“Our number one impact has been creating a space where students can come in exactly as they are, and have a team that believes in the highest they can achieve,” says DDC executive director Sasha Wells. “We help them see themselves as students with great potential, and understand that education is something they are not just worthy of, but entitled to. They come into a space where none of the labels the outside world may put on them — disadvantaged, immigrant, potential criminal, a problem that needs fixing — are attached.”

Wells and other DDC leaders understand that if those are the only messages a young person receives, it can create a lifelong set of emotional obstacles. And when students begin to doubt themselves, DDC challenges them to think outside the confines imposed on them.

“We have program alumni whose story isn’t just ‘DDC helped me get into college’ — it’s ‘DDC saved my life,’” Wells says. “That’s not an exaggeration. It’s because they found a space that didn’t continue the cycle of low expectation. We’re equipping them to prepare for those obstacles and to manage them successfully — because unfortunately, they’re not going to be able to avoid them,” she says. “And I think that’s the true brilliance of this organization.”

Columbia undergraduates and DDC students lived and learned together during the inaugural 1965 summer program.

PHOTOS COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

“DDC is a living example of how knowledge meets responsibility,” says Josef Sorett, dean of Columbia College and vice president for undergraduate education. “The intersection of students learning through service and young people imagining new possibilities for themselves affirms a simple but powerful truth: Education changes lives. This shared discovery — of ideas, of community, of purpose — is at the heart of a Columbia education, and is a commitment that matters now more than ever.”

By committing to service, undergraduates also discover things about themselves. Lehecka — who has served the College and University for decades in a variety of positions, including 19 years as dean of students — started out studying mathematics as an undergraduate. “Double Discovery showed me I had ambitions beyond what mathematicians usually have,” he says. “It changed the hierarchy of my values.”

DDC will mark its 60th milestone with a gala on Oct. 22 honoring three notable alumni: Dr. Denise De Las Nueces ’03, an addiction medicine specialist with a focus on vulnerable populations; Duchesne Drew ’89, the president of Minnesota Public Radio and a University trustee; and Khadijah Sharif-Drinkard ’93, senior VP of business affairs at ABC News. All three credit DDC for having a profound influence on their lives.

“I was exposed to mentors who believed in me and recognized my potential long before I could recognize it in myself,” De Las Nueces says. “I gained confidence in my ability to set and reach goals — even seemingly insurmountable ones.”

“DDC didn’t just shape my Columbia experience, it helped me figure out what I wanted to do with my life,” Drew says. “I progressed from being a volunteer mentor, to a work-study teaching assistant, to a full-time staff member. I became so knowledgeable and passionate about education while working at DDC that I wanted more people — not just grant officers at foundations — to know what’s possible when we make smart investments in young people from underresourced communities.”

“Not only did I attend the program, but most of my siblings did as well,” says Sharif-Drinkard. “It was a lifeline for our family — a safe and nurturing environment that provided social, emotional and academic support, all of which fueled our drive to become excellent role models for the next generation.”

“We have program alumni whose story isn’t just ‘DDC helped me get into college’ — it’s ‘DDC saved my life.’”

Critically, this year’s gala will also serve as a fundraiser. DDC lost millions of dollars of financial support in 2025, including a seven-figure federal grant that was abruptly terminated on March 7. “This is the first time in our existence that we are entirely donor funded,” Wells says.

She acknowledges it’s “a really scary time,” but adds that she has faith that things will change. “We know that obtaining education is the most impactful way to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty — and many of us here are examples of that ourselves,” she says. “As staff members, as volunteers, we’ve changed what our children’s lives look like; we’ve changed our families and our communities.”

From the beginning, Wells says, DDC’s message was not: “We need to make you worthy of Columbia.” “It’s been, ‘We know you’re so much more than what everybody has told you.’ We want our students to understand that the barriers are not their fault; that with tools and resources, they can overcome them, or manage them. And it’s been that way since DDC’s inception.”

Lehecka recalls the mid-1960s as a hopeful time. Landmark legislation — the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — was being enacted to eliminate segregation and outlaw discrimination. President Lyndon B. Johnson, prioritizing “the war on poverty,” launched The Great Society, a series of initiatives that increased federal involvement in education, employment and healthcare. Organizations like Volunteers in Service to America were established to encourage citizens to give back to society in meaningful ways.

At Columbia, volunteerism was a popular and well-supported extracurricular activity; efforts were coordinated by the Columbia College Citizenship Program, administered by a council of 50 College and Barnard undergrads. Students agreed to devote several hours a week to helping the community: tutoring underprivileged children; assisting in hospitals, emergency rooms and government offices; examining local housing conditions and organizing neighborhood tenant and block associations.

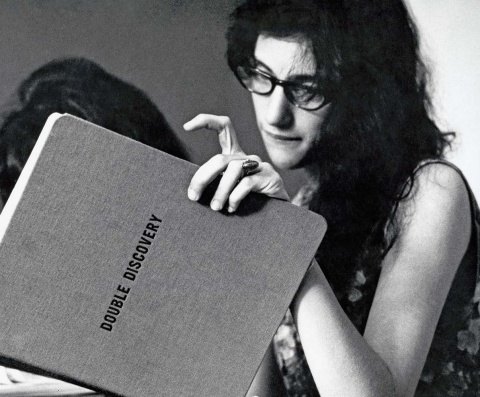

Roger Lehecka ’67, GSAS’74

JÖRG MEYER

Instead of taking the idea to the University administration, Shenton went straight to Weinberg and Lehecka. “That’s the kind of guy Shenton was,” Lehecka says admiringly. “He said to us, ‘Look, if you guys can put together a credible plan for a summer program, I’ll get Columbia’s president to sign it and send it to the government.’ In retrospect, it was ridiculous — that would never happen today! But we did what he said, he did what he said, everyone said yes, and by June we had the money.”

With $157,000 in hand, Weinberg and Lehecka recruited dozens of Columbians to work that summer; the crew created a curriculum and then invited public high school students from the neighborhood to join them on campus for an eight-week collegiate immersion. The idea was, by exposing underserved teens to Columbia life — living in the dorms, eating in the dining halls, taking classes, playing sports — they could improve the students’ experience of education; ideally, the program would inspire them to not only complete high school, but to think of college as an attainable option. (CUNY ’s Open Admissions plan, which guaranteed a spot to every NYC high school graduate, had not yet been implemented.)

Project Double Discovery (PDD) launched a month later with 160 high school students and 40 from the College and Barnard. (The name changed to Double Discovery Center in 1985; Lehecka’s name was added in 2016.) The University hired a NYC high school principal as the director; he brought in public school teachers to lead classes on weekday mornings. In the afternoons and on weekends, the collegians were in charge — living among the students and serving as tutors, mentors and role models. Weinberg and Lehecka kept an office in Hartley Hall; officials from Washington, D.C., stopped in occasionally to see how it all was going.

“It was eight weeks non-stop — we were exhausted, but it felt great,” Lehecka says. “We thought we were not just helping individual students, but showing that students who maybe weren’t successful, could be successful. We thought we were doing something that could change public education, and I think that made all of us more enthusiastic.”

By the following summer, the OEO’s campus pilot project had become Upward Bound, a national, federally funded college prep program for first-generation, low-income students. And PDD’s format had been so successful that the OEO not only doubled its funding for 1966 but made having an immersive summer program a requirement for all UB projects.

Weinberg eventually moved on; Lehecka gave up his math studies to focus on education. He stayed on as a PDD administrator through the summer of ’67; the following year, increased funding allowed PDD to become a year-round program and Columbia brought on full-time leadership. “By that time, undergraduates were more involved in more political things,” Lehecka says. “If Double Discovery had been left to student oversight it probably would have gone away.

“But we did it, and it worked. It worked — and it’s still working, 60 years later.”

Making it work at DDC! Left to right: student staffers Hayley Arleny Morales DDC’24 and Genesys Vasquez Ocumares DDC’23; Rabiyya Smith, associate director of academic enrichment; Sasha Wells, executive director; Day Harris-Drake, associate director, Healthy Minds & Bodies; and Gizzel Edmund, associate director, College Access Programs.

JÖRG MEYER

Education and service continue to be the cornerstones of DDC’s winning formula. The program is centered on a holistic approach to students’ development, with activities focused on three pillars: academic enrichment, college and career success, and healthy minds and bodies. The majority of work takes place on weekends during the school year — at a daylong program known as Saturday Academy — and during the summer.

All told, DDC currently has an enrollment of 300 students, representing dozens of partner high schools. (The program used to be solely for students residing and/or going to school in Morningside Heights, Washington Heights and Inwood; DDC expanded its reach in 2022.) Typically, college access programs focus on juniors and seniors, but DDC likes to make connections earlier — with ninth-graders — in order to help them explore their interests. Then DDC staff can best guide the direction of their college applications. “Their interests will affect what they want to major in, what school they apply to and the foundation for their college essay,” Wells says. “It also helps students decide how to communicate about themselves, and ultimately, how they’ll advocate for themselves in college.”

This past August, 50 high schoolers completed the now five-week summer program, Summer Academy; because of economic constraints, it was non-residential for the first time. “That was a huge loss, and we were concerned the students wouldn’t show up every day — coming from all boroughs, some of their commutes can be an hour each way,” Wells says. “But we actually had close to 90 percent attendance daily. They were engaged and excited, and it went really well.”

DDC students participate in a variety of academic enrichment activities, including literature, history, writing, sociology and STEM courses over the summer and on the weekends during the school year.

Diane Bondareff

The DDC office space itself provides a secure environment in which to grow, and students often hang out there until closing time. “For decades, it’s literally been a safe haven for kids whose only other options were going to be crime, drugs, gangs or prison,” Wells says. “Sometimes our high school students are in environments that are impossible to manage. And it’s just getting harder.”

Volunteerism is the other essential element to DDC’s success. Participating undergrads commit to a minimum of two hours (with a maximum of six) per week. Each Spring, Lehecka co-leads a seminar, “Equity and Access in Higher Education,” for which four hours of DDC service is a requirement.

“Our undergraduates frequently tell us their time at DDC has really made their Columbia experience,” Wells says. “It’s a place where they feel supported, they feel seen and heard. And they get the added benefit of helping [high school] students — which they themselves were just a few years ago — to be achieving the same.”

Many volunteers gain an understanding of educational and socioeconomic inequities for the first time through their work at DDC; others know those realities all too well, and are motivated to guide students like themselves toward a better path.

“They’re getting such a tremendous education at DDC,” Wells says. “Many of the undergrads who have come through our doors go back changed, wanting to do something like policy or law or education, because they have now seen firsthand what the result is when you don’t have anyone invested in that. We’re enabling a whole new set of leaders to go change the inequities that exist.”

Looking ahead, after being grant funded for decades, DDC will have to change some of how it does things. What is unchanged is the need for the program. “We’re trying to affect not just a student, but a family and a community circumstance,” Wells says. “We want that student to contribute back their success to their family and to their community, so that the next generation isn’t suffering the same challenges. And that is significant.”

Lehecka agrees. “The way I look at it, the right way to think about Double Discovery is not just as a Columbia program,” Lehecka says. “It’s actually an important resource to New York City. And because of that, any sensible New Yorker should want to support it.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu