Jennie Erin Smith ’95 spent years reporting on a community in health crisis

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Jennie Erin Smith ’95 spent years reporting on a community in health crisis

SETH ROBBINS

In 2016, Smith saw a 60 Minutes segment about a far-flung community in rural Colombia where an extended family shared a rare gene mutation that resulted in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease; a neurologist named Francisco Lopera had put years into researching the mutation, hoping the cluster of cases held clues to a breakthrough. But what kind of progress was possible? Who were these families? What were their lives like, and how did it feel to be subject to such long-running scrutiny?

Smith wanted to know more. She emailed a professor who’d been interviewed for the episode and, with his encouragement, went on to immerse herself in what became a seven-year project. She moved to Medellín — which remains her home nearly 10 years later — befriended afflicted families and visited the clinics where patients participated in clinical drug trials. She also met with Lopera himself.

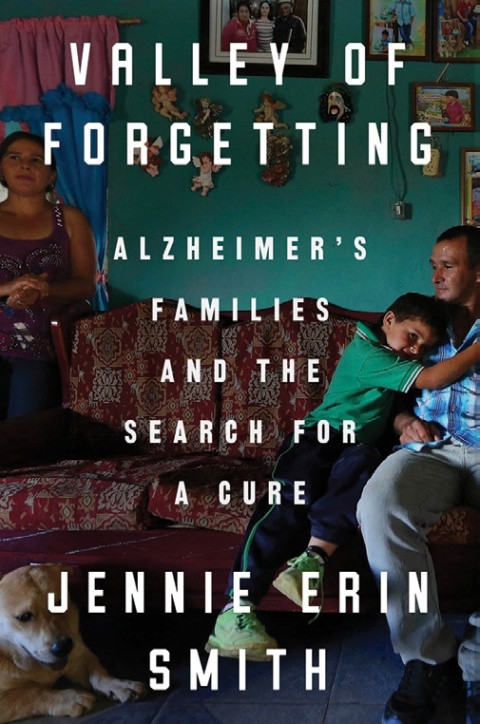

The result is Smith’s second book, Valley of Forgetting: Alzheimer’s Families and the Search for a Cure (Riverhead Books, $30). In it, she creates what is foremost an intimate and heart-rending portrait of the Colombian Alzheimer’s families — the impact of the disease on patients and caregivers, as well as their experiences with the world-class research program that was built around them. The latter opens up larger questions about the ethics and moral stakes of this type of scientific inquiry.

Smith not only spent time in the homes of the patients she was documenting, but she also routinely socialized with them, attending their weddings and parties — and their funerals. “Six siblings dead before age 60 did not impress the people who had gathered here, and no one mentioned Alzheimer’s disease,” she writes. “What was Alzheimer’s but another way to die, in a place where early death was unremarkable?”

Smith even took a young woman named Daniela Lopez Pineda under her roof. She met her family after its matriarch, who died of Alzheimer’s, underwent an autopsy. Smith had already built up enough trust in the community that the family wanted her to attend. “They didn’t necessarily trust the researchers,” she says. “They wanted me to be present, to report back to them when researchers were doing something behind closed doors.”

Asked if getting so close to her subjects made her a less than objective reporter, Smith says no. “I’d rather err on the side of generosity and help people where I can, especially when I was criticizing researchers for not helping enough.”

The daughter of a physician, Smith started at the College on the pre-med track. “I always had a lot of curiosity about science, and biology and medicine were huge interests of mine,” she says. (She ultimately switched majors to pursue “another great love,” East Asian studies.) Smith freelanced for years as a medical reporter; coincidentally, in 2011, she and her husband spent a year in Colombia learning Spanish.

In addition to a story about medical research, Smith documents life in an impoverished region during a violent period in its history. She describes the lives of orphans forced to fend for themselves, adults who believe witchcraft causes Alzheimer’s and a drug-gang driver who jokes about making her his prisoner. “I wanted to force the reader to reckon with how people live here,” she says. “I felt all along that writing about Colombian life was something like contraband I needed to smuggle into the story. I wanted it to be front and center,” she says.

One big challenge, Smith says, was the “intransigence” of some of the Colombian doctors. “Over the years they began to tell the story of their research in ways that suited them,” she says. “They had their own narratives and version of events. Some didn’t want to be forthcoming at all. And I just didn’t have the level of comfort with them that I had with the families.”

Her Valley of Forgetting research followed two paths. Because many of the papers published by the Colombian doctors were not publicly available, Smith had to locate physicians who had collaborated with the Medellín researchers over the years. “Finding those people allowed me to not have to depend on the main investigators,” she says.

Meanwhile, she simultaneously approached families in a “completely opportunistic and haphazard way,” she says. “I was not content to see them once. I wanted to see how they lived with the disease, and that meant following up with them many times.”

Smith is no stranger to deeply researched projects. She followed a similar strategy when writing her first book, Stolen World: A Tale of Reptiles, Smugglers, and Skulduggery, about the illegal trade in exotic wildlife. Published in 2011, it took nearly 10 years to complete.

In this excerpt, Smith introduces both the paisa mutation that was devastating families around Medellín and the research institution established by Lopera, Grupo de Neurociencias de Antioquia. She begins to unpack the mystery of why so many young people in one small corner of the world were having their lives cut short by early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Smith says she’s always liked being out in the field and taking time to get to know her subjects. And for Valley of Forgetting, she says, “living the story” made her book unique.

“I had access to a candid bunch of people I could follow over time. There was no stage managing,” she says. “I got a different story than other people were able to get.”

George Spencer is the co-author of When Memory Fades: What to Expect at Every Stage, from Alzheimer’s Early Signs to Full Support (St. Martin’s Press, 2026).

Now that Medellín had finally calmed down after decades of violence, foreign researchers had come to see in this family an ideal testing ground for drugs that might stop Alzheimer’s disease before it could take hold. One pharmaceutical company had poured more than $100 million into a clinical trial at the Grupo de Neurociencias — or just Neurociencias, as the researchers called it — to test a drug called crenezumab in the paisa mutation families. Among the participants Lopera and his team enrolled in this trial were the children and grandchildren of Pedro Julio Pulgarín and his siblings, people he had first come to know as a young doctor and had painstakingly followed for generations.

In Gabriel García Márquez’s novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, the traveling gypsy Melquíades cures the residents of Macondo, a fictional town in northern Colombia, of a mysterious disease causing them to lose their memories and their sleep. García Márquez was not aware, at the time he was writing, of the families with Alzheimer’s disease in the mountains of Antioquia, but the similarities were striking, and the investigators alluded to them in interviews with newspapers and TV stations. Would crenezumab prove to be, as they dearly hoped, like the magic elixir of Melquíades? It would be several years before anyone knew, and expectations remained high.

The crenezumab trial was just the largest and most expensive of all the studies going on at Neurociencias. With such a large early-onset Alzheimer’s population, the number and type of studies you could design — whether in imaging, neuropsychology, pathology, or cell biology — were almost infinite.

Dr. Francisco Lopera, second from right, in Yarumal, Colombia, in 2010. Oderis Villegas, center, was showing signs of Alzheimer’s disease at age 50; a sister, María Elsy, left, had a more advanced case.

TODD HEISLER / THE NEW YORK TIMES

Only part of this story belonged to the scientists. The rest belonged to las familias, as the investigators referred to their thousands of research participants. Since the 1990s, they had donated hundreds of their loved ones’ brains to Neurociencias. They had subjected themselves to scans, spinal taps, and infusions of radioactive compounds. Now many were receiving injections of an experimental drug that might not even become available to them if it worked, given the vagaries of the global pharmaceutical trade and strained budgets for healthcare in Colombia.

Neurociencias hosted frequent visits from journalists and film crews. They came from Germany, Japan, the United States, or the United Kingdom seeking interviews with Francisco Lopera, the charismatic doctor with the near-constant smile and thick white mane, and with the families living in bucolic hamlets or humble city houses who nursed their sick beloved. The family members presented to the media tended to be people with only praise for the investigators and high hopes for a breakthrough. But this left a lot unsaid about how they shouldered the burden of their inheritance over months, years, generations. How did the specter of early Alzheimer’s shape their lives and decisions? Were they as intent as the scientists on unlocking the mysteries of their disease? How did it feel to be part of a study that had enrolled their parents and grandparents, and would one day enroll their children? If the current clinical trial failed, would they despair?

The family members seldom knew whether they carried the paisa mutation, and the handful interviewed by the media often said they did not wish to — they preferred to trust in God. I wondered about this. I had lived in Colombia before, and knew that it was a country of faith, perhaps nowhere more than in Antioquia. But it was also a country of rising education levels and changing concepts of personal freedom. More people lived in cities than in rural areas; more women worked than stayed home. Fertility rates were only barely higher than in the United States, and even a longtime ban on abortion was being eroded. It stood to reason that there would be some people in this cohort of six thousand — young people especially — who would want to learn whether they carried a mutation that destined them to fall into dementia by their forties, to have their lives cut in half.

From Valley of Forgetting: Alzheimer’s Families and the Search for a Cure by Jennie Erin Smith. Copyright © 2025 by Jennie Erin Smith. Excerpted by permission of Riverhead Books.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu