Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Wm. Theodore de Bary ’41, GSAS’53: “The Soul of Columbia College”

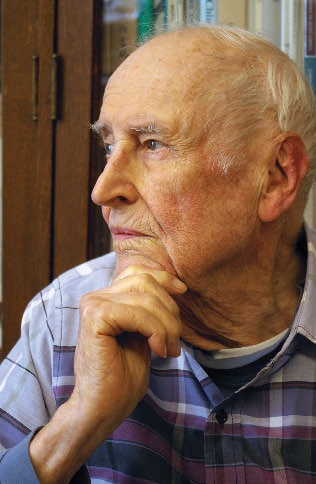

Wm. Theodore de Bary ’41, GSAS’53, the John Mitchell Mason Professor Emeritus and Provost Emeritus, died at home in Tappan, N.Y., on July 14, 2017, less than a month before his 98th birthday.

ROSS YELSEY

Renowned for his scholarship in East Asian religion, thought and society, de Bary taught on Morningside Heights for seven decades, earning admiration across the globe as an educator of formidable commitment, dignity and character.

He founded Columbia’s influential programs in Asian studies, including the groundbreaking undergraduate curriculum in Asian Civilizations and Asian Humanities he developed to complement the College’s signature courses in the Western tradition. “Ted de Bary was a truly great Citizen of Columbia on every level, as an accomplished student, visionary scholar and respected academic leader,” said President Lee C. Bollinger in a statement to the University community. “To the last, he was a beloved teacher and friend who remained devoted to his alma mater. And for that, generations of fellow Columbians will always be grateful.”

Following the example of dedicated teachers of prior generations, de Bary championed the integrity of the College faculty and the Core Curriculum, upholding the Core’s vitality and value not as an unchanging canon, but as an ever-evolving responsibility: to confront students with a common body of significant, enduring texts taught by a committed interdepartmental staff in small discussion sections. “He was deeply engaged with the Core Curriculum in all its dimensions,” said Dean James J. Valentini. “His impact on the College has been far-reaching and will long continue to be felt.”

De Bary’s achievements earned him many honors, including a John Jay Award in 1989; the Alexander Hamilton Medal in 1999; the National Humanities Medal, given at the White House in 2014 by President Barack Obama ’83; and, in 2016, the prestigious Tang Prize in Sinology, recognizing his pioneering contributions in Confucian and NeoConfucian studies.

Born in the Bronx on August 9, 1919, de Bary was raised by a single mother in Leonia, N.J., where he attended public schools. In 1937, he was offered a scholarship to the College. In undergraduate classes with historians Carlton Hayes (Class of 1904, GSAS 1909) and Jacques Barzun ’27, GSAS’32, philosopher Ernest Nagel GSAS’31 and many others, de Bary discovered a world of intellectual challenge, an experience he treasured. He was a campus leader, heading up the Debate Council, the Van Am Society and the student government. He dove into the city’s jazz scene, catching Duke Ellington, Count Basie and other famed bands in Harlem and Greenwich Village. De Bary met his future wife, Fanny Brett BC’43, at a tea dance in Brooks Hall during his junior year. They were married for 67 years, until her death in 2009.

Recruited to U.S. Naval Intelligence shortly after Pearl Harbor, de Bary served in the Pacific theater. He was a doctoral student at Columbia in 1949 when Dean Harry J. Carman GSAS 1919 asked him to develop the Asian Core programs, a labor that entailed the creation of source books — texts, in translation, of classic works — employing the talents of such eminent scholars and translators as Donald Keene ’42, GSAS’49, de Bary’s close friend and colleague for three-quarters of a century. De Bary chaired the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures 1960–66, when he was named the Carpentier Professor of Oriental Studies. In the aftermath of the 1968 student uprising, he chaired the Executive Committee of the newly formed Columbia University Senate. He was appointed EVP for academic affairs and provost — the University’s highest academic office — in 1971, serving until 1978.

De Bary officially retired in 1989, but continued teaching on a voluntary basis for another 28 years. He graded the last papers for his Spring 2017 courses — Asian Humanities and his seminar, “Nobility and Civility” — in May. “For more than half a century, Ted de Bary has been the soul of Columbia College,” Andrew Delbanco, the Alexander Hamilton Professor of American Studies, told CCT in 2013.

It would be fair to ask if there has ever been a more true-blue Columbia loyalist than Ted de Bary. He attended his first football game at Baker Field as a schoolboy in 1927; as an alumnus (with the exception of sabbatical leaves), he did not miss a home game for more than 50 years. His legacy includes the creation of such institutional enrichments as the Heyman Center for the Humanities, the Society of Senior Scholars and the University Lectures.

He also made innumerable lesser-known contributions to campus life. In the mid-1970s, de Bary played a crucial role in the rescue of Reid Hall, Columbia’s 18th-century academic center in Paris, which the trustees had considered selling to help close a budget shortfall. He and his wife made a substantial donation toward the establishment of the Wm. Theodore and Fanny Brett de Bary and Class of 1941 Collegiate Professorship of Asian Humanities. In 1995, they donated the Peace Altar in St. Paul’s Chapel, fashioned by the celebrated Japanese-American woodworker and designer George Nakashima. A fixture at class reunions, award dinners and many other campus events, the de Barys had four children, three of whom survive them: Brett BC’65; Paul ’68, LAW’71, BUS’71; and Mary Beatrice de Bary-Heinrichs GSAS’84. A daughter, Catherine de Bary Sleight BC’73, JRN’77, died in 2010. Between them they had eight grandchildren, three step-grandchildren, three great-grandchildren and a step-great-grandson.

Tucked amidst de Bary’s scholarly works — he wrote or edited 33 volumes — there are passages that illuminate the purity of his mission as a teacher. In his final book, The Great Civilized Conversation: Education for a World Community (2013), de Bary describes one of his chief mentors, Ryūsaku Tsunoda, considered the father of Japanese studies at Columbia, whom both de Bary and Keene referred to, simply, as Sensei, or teacher.

“This unpretentious, undogmatic teacher had no special message, claimed no special authority, demanded no obedience to his person,” de Bary wrote. “Like Confucius, he forgot himself in his wholehearted devotion to study. There was never a class or lecture that he did not spend hours in preparation for. There was never a student in whom he did not take a personal interest, though he could be severe as well as sympathetic. There was hardly a day on which he did not make some intellectual discovery for himself and joyfully share it with anyone around the office or library who might understand.”

De Bary shared his teacher’s devotion and joy and never strayed. His contributions are likely to endure as long as the students of his students continue to impart his love of reason and community, his allegiance to freedom of conscience and expression, and his dedication to civilized discourse within and among the world’s many great cultures and traditions.

Former CCT Editor Jamie Katz ’72, BUS’80 contributed a profile of de Bary, “Loyal to His Core,” to the Fall 2013 issue.

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu