Contemporary art curator Rujeko Hockley ’05 is about to open her biggest show yet — the 2019 Whitney Biennial.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Contemporary art curator Rujeko Hockley ’05 is about to open her biggest show yet — the 2019 Whitney Biennial.

Hockley at the Whitney Museum of American Art; behind, Salon Hodler by Louise Lawler

Jörg Meyer

The embargo is made clear, apologetically but firmly, within the first few minutes of our conversation about the upcoming Whitney Biennial — that ambitious, much-anticipated and often controversial survey of what’s worth knowing in contemporary American art. Hockley is co-curating the show, set to open May 17, and when we first spoke last September, invitations to participate were still going out. In fact, she and co-curator Jane Panetta were still meeting artists for consideration — a tour that had them crisscrossing the country from Portland to Cleveland, to Miami and Puerto Rico.

“That’s one of the interesting things about a biennial,” Hockley says. “You’re making it up as you go. I mean that in the best possible way — you don’t get to do all the thinking, make all the decisions and then start inviting people to be a part of it. You do it as you go because that is what is required by the nature of the timing.” The process moves quickly, she says, and calls for a focus on the details and the big picture all at once: “As a show that happens every two years, it has its own cycle and metabolism.”

The pace is not entirely new to Hockley, who’s been in high gear since moving to the Whitney Museum of American Art two years ago. For a while she still had one foot in her former home, the Brooklyn Museum, shepherding a major exhibition about black female artists that then traveled to three other locations. At the Whitney, she immediately joined a team developing a collections show that looked at almost 80 years of protest art and how artists have confronted the political and social issues of their day. Then came the Biennial appointment. Hockley also shares that she’s pregnant — “It’s an especially busy year, it turns out, even more than I planned.” Considering the magnitude of the undertaking that is the Biennial, this seems a rather understated take on Hockley’s 2018.

Then again, maybe that’s an equanimity that comes from taking on a challenge of just the right shape and size. Hockley brings a résumé that also includes a curatorial role at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and throughout her career — and even before, as an art history major at the College — she has focused on questions of equity, access, inclusion and history. The Biennial, the signature of an institution that has long queried and redefined what it categorizes as American, falls right in her wheelhouse. One way to define the show, Hockley says, is as “an every-two-year check-in on ‘What do we mean when we say ‘American,’ and when we say ‘American art’?”

Given the current political and cultural climate, it’s a charged moment to offer an answer. But maybe that’s why it’s also a moment when the Biennial, and art in general, can play an especially vital role. “One of the things that art can do is allow us to have perspective — to look at the macro, the span of human history, the span of human behavior, hundreds of years, thousands of years,” Hockley says. “But I think it also allows us to use a different part of our brain and a different part of our heart, a different part of our being, to think about things.”

The Brooklyn Museum exhibition that had Hockley running between boroughs, back when she started at the Whitney, turned out to be one of the most significant of her career. “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85” explored how black female artists of that era contended with a double exclusion: a second-wave of feminism that largely belonged to white women, and a black community that increasingly wielded art as an expression of civil rights — even as it embraced a Black Power sexism that gave the platform to men to do the expressing. Put another way, as The New York Times wrote in its apt headline, the show captured what it was like “to be black, female and fed up with the mainstream.”

Emma Amos’s 1966 painting “Flower Sniffer” was bought by the Brooklyn Museum after appearing in “We Wanted a Revolution,” a show co-curated by Hockley.

For Hockley, it has been especially meaningful to see what happened afterward. “The show continues to have a life in the world,” she says, partly because its featured artists — many of whom had been underrecognized despite being long established in their careers — are becoming more widely known. Hockley explains that some are winning gallery representation, landing solo shows at museums, having their work acquired by significant institutions. Painter and printmaker Emma Amos had paintings from “We Wanted a Revolution” purchased by the Brooklyn Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art. Sculptor Maren Hassinger’s wire and wire rope installation, which greeted visitors at the exhibition’s entrance, was acquired for the permanent collection at MoMA.

“This is the impact of doing a historical show that adds to the historical record and adds new, original research and thinking to a time period that is felt to be well known — it can have real ramifications,” says Hockley. “It can really change not only art history but it can also, actually, really change people’s lives, the artists themselves. That’s been a great lesson and an amazing privilege.”

The possibility and the power of a historical collection is also a lesson Hockley took, more broadly, from her time at the Brooklyn Museum. “Like the Metropolitan, it’s an encyclopedic museum going from ancient Egypt to contemporary art. To have colleagues who are versed in such a wide array of disciplines and who have such deep knowledge that is totally different from my knowledge was amazing and important,” she says. And from the Studio Museum — which has a renowned artist-in-residence program and mission grounded in championing artists of African descent — she carries one of her core tenets: “As a curator who’s invested in contemporary art, who works with living artists, you take your cue from them. Your job is to support them and their vision, first and foremost.

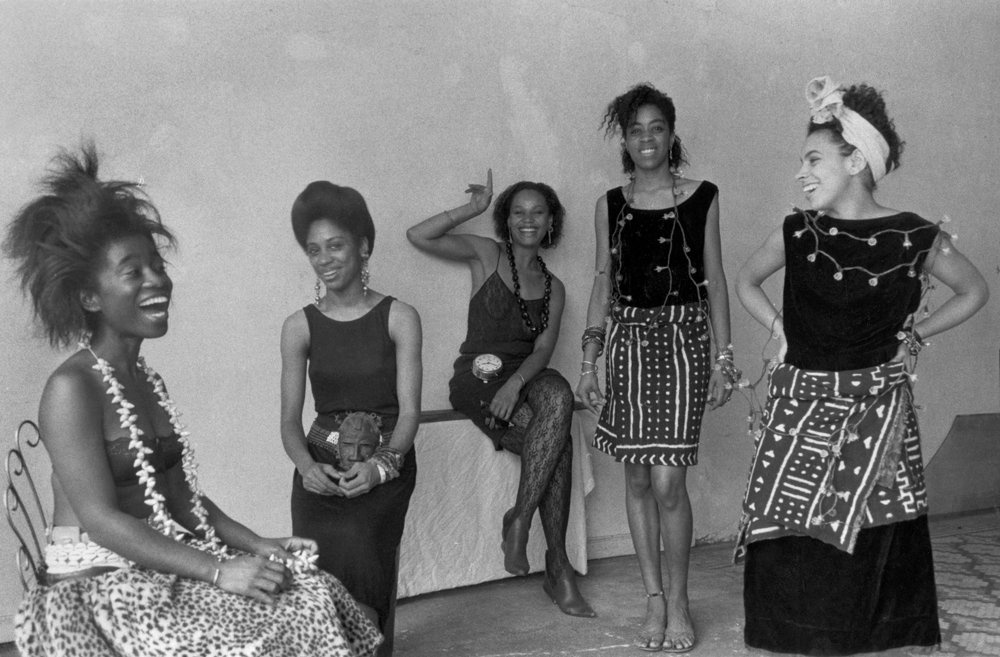

Lorna Simpson’s 1986 photograph “Rodeo Caldonia,” featuring members of the eponymous theater collective, from the exhibition “We Wanted a Revolution.”

COURTESY LORNA SIMPSON AND HAUSER & WIRTH

The Whitney Biennial is the longest-running continual survey of American art. It debuted in 1932, just a year after the Whitney opened, when Paris ruled the art world and any appetite for art was essentially for European works. Both museum and show were bold declarations that what artists were doing on this side of the Atlantic was worth paying attention to. (The museum also was socialite and sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s response to having her personal collection — more than 500 sculptures, paintings, drawings and prints by living American artists — rejected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.) Nearly 80 years later the Biennial has become, as The Village Voice described it on the eve of the 2017 installment, “an undeniable gale force in the unruly landscape of American art.”

It’s worth noting here that Hockley is an immigrant. Her mother is from Zimbabwe and her father from Britain. Hockley was born in Zimbabwe but has a green card and has lived in the United States for much of her life. She recognizes there’s a certain irony to being the curator of this distinctly American show, but also, she laughs, “Whatever! Who’s more attuned to a place? It can be the person who’s [on the outside].”

Jörg Meyer

As for the works they’re tapping for the show, Hockley describes the selection as an iterative process. Rather than begin with a vision or themes, “the artists’ visits that we went on led us to different visits, and to different ideas, and we followed that thread intuitively — taking our cues from the work they were making, the things they were saying to us and what they were interested in — and built the show that way.” (In the end, she and Panetta will make approximately 300 studio visits.)

Hockley resists any interpretation of the Biennial as an attempt to be definitive or prescriptive about the state of modern art. “Every Biennial is subjective to the people who are doing it — different curators could have done the same route of travel and studio visits and come up with a totally different show. … There are many things happening and no two people could ever see them all and know them all, especially because the art world has grown so much in the last several decades.”

When Hockley and I catch up again in mid-January, she still can’t discuss the artists (by the time this article publishes, the cloud of secrecy will have dispelled). She can, however, offer a little more by way of her and Panetta’s vision: “In a really overarching way we’re interested in thinking through and looking at the ways that artists are thinking about history, thinking about the past, and reframing it for the present and for the future.”

We can finally talk about it! Peep our site now for Biennial preview images: college.columbia.edu/cct/latest/

feature-extras.

Will she look at the reviews? “For sure, I’m only human,” she says with a laugh, “whether that’s a good idea or not. It’s interesting to know what is or isn’t landing, and I want to know what other people think about the work that I do.

“People always have something to say about the Biennial,” she adds. “It attracts a lot of attention, which is part of the privilege of it. We are able to give all of these artists what amounts to a very large platform, and that is profound and meaningful and we take that seriously. The thing I hope — which is always the thing I hope when I work with artists especially — is that they feel proud of the way their work is shown and the way they are represented; that they come and they say, ‘Oh wow, this is amazing. These people really did well by us.’”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu