Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Exposing a Buried Past

Photographer Daniella Zalcman '09 sheds light on a dark time in Canadian history with her award-winning project, Signs of Your Identity.

In 2014, Daniella Zalcman ’09 began reporting on a part of North American history she felt had been erased from the continent’s narrative — part of the lesser-known “cultural genocide” that followed the decimation of Native American societies. Between 1870 and 1996, thousands of indigenous children in Canada were removed from their homes and sent away — sometimes hundreds of miles — and forced to learn to assimilate in Indian residential schools. Zalcman wanted to document some of the more than 80,000 survivors of this trauma. “Children were made to believe ... that they needed to be more white, that they needed to be more Western,” Zalcman told CCT. They were made to give up Native language and practices and in many instances were victims of physical and sexual abuse. The lessons they remember, as adults, are those of cruelty.

Daniella Zalcman ’09

ANGELA RADULESCU ’11

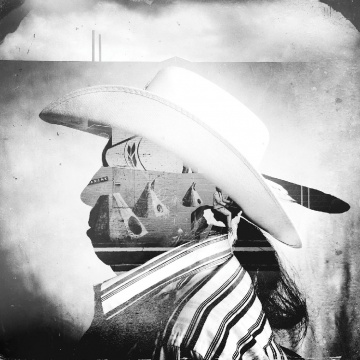

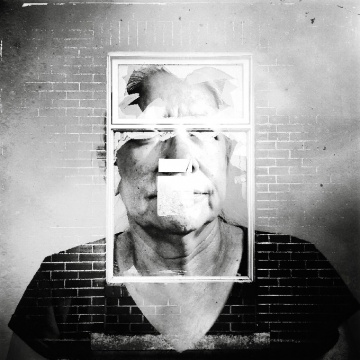

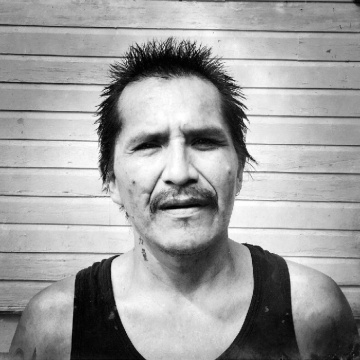

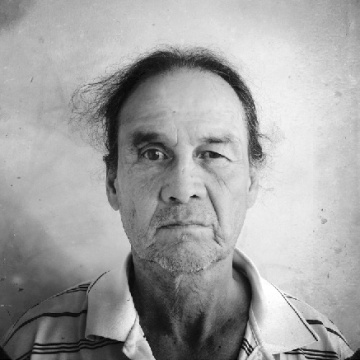

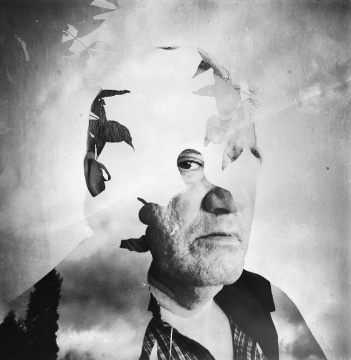

Though she had created conventionally “good” images of her subjects in Canada, Zalcman felt they didn’t have the appropriate gravitas. “For me, a straight series of portraits wasn’t going to be enough to tell that story,” she says. So she added another dimension: Each portrait would include an overlaid image of “something that had to do with their memory, their experience in residential schools.” The double exposure, an “extra layer of storytelling” as Zalcman calls it, resulted in a project that has won her multiple honors, including the Magnum Foundation’s Inge Morath Award in 2016, the 2016 FotoEvidence Book Award, and, most recently, a 2017 Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award.

Zalcman got her professional start freelancing for the New York Daily News in between undergraduate classes as an architecture major. After graduation, she became a daily assignment photographer at the News, then at The Wall Street Journal. She now travels between bases in London and New York and is a contributor to outlets as diverse as Vanity Fair and Mashable. Her work is also featured in the permanent collection at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.

Zalcman says she’d like to continue working on long-term projects that “explore the legacies of Western colonization.” In an 2016 interview with the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting — which funded her research — she muses about students of history and how much she wants them to learn the narratives that might be missing from their textbooks. And if her work can help expose rich layers of a buried past, so much the better, she says. “The act of acknowledging ... is really important, psychologically.”

— Rose Kernochan BC’82

INDIAN ACT OF 1876 – Section 119(6)

“A truant officer may take into custody a child whom he believes on reasonable grounds to be absent from school contrary to this Act and may convey the child to school, using as much force as the circumstances require.”

For 120 years, the Canadian government operated a network of Indian Residential Schools that were meant to assimilate young indigenous students into western Canadian culture. Indian agents would take children from their homes as young as two or three and send them to church-run boarding schools where they were punished for speaking their native languages or observing any indigenous traditions, routinely sexually and physically assaulted, and in some extreme instances subjected to medical experimentation and sterilization.

The last residential school closed in 1996. The Canadian government issued its first formal apology in 2008.

SERAPHINE KAY

QU’APPELLE INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1974–75

“I was raped at school. He was an old man, the janitor. I didn’t tell anyone for decades, because I thought people would judge me. The only person I ever told was my mother [who went to Muskowekan Residential School]. All she said was ‘that was how I was brought up, too.’”

SERAPHINE KAY

QU’APPELLE INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1974–75

“I was raped at school. He was an old man, the janitor. I didn’t tell anyone for decades, because I thought people would judge me. The only person I ever told was my mother [who went to Muskowekan Residential School]. All she said was ‘that was how I was brought up, too.’”

MIKE PINAY

QU’APPELLE INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1953–63

“It was the worst ten years of my life. I was away from my family from the age of six to 16. How do you learn about family? I didn’t know what love was. We weren’t even known by names back then. I was a number.”

“Do you remember your number?”

“73.”

MIKE PINAY

QU’APPELLE INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1953–63

“It was the worst ten years of my life. I was away from my family from the age of six to 16. How do you learn about family? I didn’t know what love was. We weren’t even known by names back then. I was a number.”

“Do you remember your number?”

“73.”

VALERIE EWENIN

MUSKOWEKAN INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1965–71

“I was brought up believing in the nature ways, burning sweetgrass, speaking Cree. And then I went to residential school and all that was taken away from me. And then later on, I forgot it, too, and that was even worse.”

VALERIE EWENIN

MUSKOWEKAN INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1965–71

“I was brought up believing in the nature ways, burning sweetgrass, speaking Cree. And then I went to residential school and all that was taken away from me. And then later on, I forgot it, too, and that was even worse.”

FARRELL RUNNS

MONTMARTE CONVENT SCHOOL 1975–85

“It was unbelievably hard, staying in that school all year round. I was strapped, I was abused. I just wanted to go home and be with my family.”

FARRELL RUNNS

MONTMARTE CONVENT SCHOOL 1975–85

“It was unbelievably hard, staying in that school all year round. I was strapped, I was abused. I just wanted to go home and be with my family.”

RICK PELLETIER

QU’APPELLE INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1965–66

“My parents came to visit and I told them I was being beaten. The teachers said that I had an active imagination, so they didn’t believe me at first. But after summer break they tried to take me back and I cried and cried and cried. I ran away the first night, and when my grandparents went to take me back, I told them I’d keep running away, that I’d walk back to Regina if I had to. They believed me then.”

RICK PELLETIER

QU’APPELLE INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1965–66

“My parents came to visit and I told them I was being beaten. The teachers said that I had an active imagination, so they didn’t believe me at first. But after summer break they tried to take me back and I cried and cried and cried. I ran away the first night, and when my grandparents went to take me back, I told them I’d keep running away, that I’d walk back to Regina if I had to. They believed me then.”

GRANT SEVERIGHT

ST. PHILLIPS INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1955–64

“We as a people have normalized every conceivable dysfunction that we experienced in residential school. Negativity is transmitted — and, if we don’t deal with it, we pass it on. Even in school, kids who themselves were terrorized grew up to be abusers. We need to figure out how to heal from that.”

GRANT SEVERIGHT

ST. PHILLIPS INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL 1955–64

“We as a people have normalized every conceivable dysfunction that we experienced in residential school. Negativity is transmitted — and, if we don’t deal with it, we pass it on. Even in school, kids who themselves were terrorized grew up to be abusers. We need to figure out how to heal from that.”

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu