Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

High Noon and Hollywood History

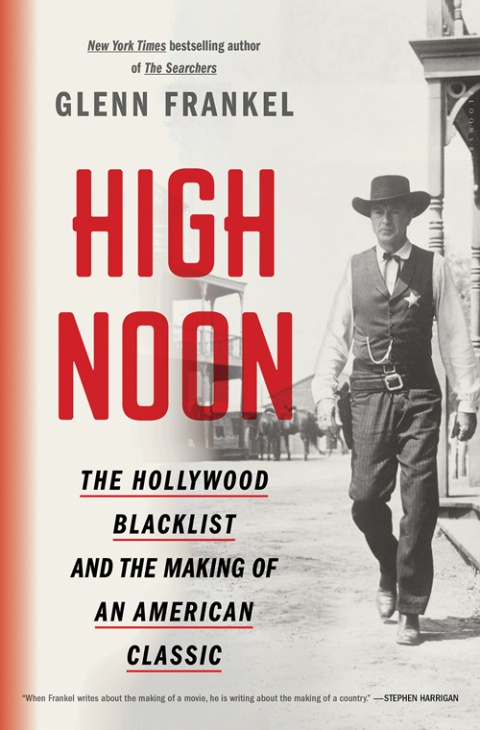

After a successful career as a foreign correspondent, what do you do for a second act? For Glenn Frankel ’71, a lifelong cinephile, the decision was easy. Wearing his new hat as a film historian, Frankel first explored the history — and mythology — of the American West in his 2014 book The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend. For his latest, High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic (Bloomsbury USA, $28), he uses another iconic Western as a lens through which to examine a tumultuous moment in American politics.

Frankel’s reinvention was driven by his desire to avoid cliché. After retiring from The Washington Post in 2006, Frankel knew he “didn’t want to be one of those foreign news experts living in Washington or California,” he says. “You get stale very quickly.” Instead, he accepted a position teaching journalism at Stanford and began research on the 1956 film The Searchers. “I thought it was just going to be a ‘making of the movie book:’ John Wayne and John Ford go to Monument Valley.” Instead, Frankel quickly became fascinated by the true story on which the film was based and plunged into its history — that of 1830s Texas and the Comanche wars. “Half the book is about the wars and half the book is about the movie and the evolution from one to another.”

Frankel’s attraction to the confluence of history, politics and popular culture has its roots in his College years. Despite a passing familiarity with New York City (thanks to relatives in the outer boroughs) and liberal politics (thanks to his working-class Jewish family), the 17-year-old from Rochester “felt like an alien” when he arrived on campus in fall 1967. “My politics were left but not coherent,” he says. When the protests began in spring 1968, Frankel remained primarily a bystander. “I didn’t sleep in any of the buildings, but I stood outside and chanted a little of this and that.” But what Frankel witnessed on campus that spring shaped his choice of career. “As a journalist, I could be an insider and an outsider at the same time … I had embraced neither the institution nor the radicals who sought to destroy it.”

Betsy Ellen Yeager

After this turbulent start, Frankel’s subsequent years at Columbia were marked by discoveries of a more purely intellectual nature. A history major, he delighted in Eric Foner ’63, GSAS’69’s African-American history seminar and David Rothman ’58’s American social history course. Andrew Sarris ’51, GSAS’98 had recently begun teaching his introductory film course in Butler’s basement. “That’s when I saw The Searchers for the first time as an adult. Sarris was so good and showed so many wonderful movies,” Frankel recalls. Frankel continued his film education at the nearby Thalia and New Yorker theaters, by his own calculation spending more time there than he did in class.

Upon graduation, Frankel landed a job as a clerk in the Museum of Modern Art’s film department, where he fed his cinephilia and says he might have pursued a career but for a girlfriend who wanted to hitchhike to San Francisco. So he quit that job, married the girl and by 1979 had arrived at The Washington Post. Frankel spent much of the next two decades overseas, covering South Africa at the height of apartheid and the Middle East during the first Palestinian Intifada. In 1989, his “sensitive and balanced reporting from Israel and the Middle East” was recognized with the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. Held in Low Library, the awards ceremony marked Frankel’s Columbia homecoming, the library’s steps transformed from the scene of student protests to the path of professional achievement.

Frankel’s new book draws upon his years as a journalist in both its exemplary research and ethical orientation. “I’m interested in people and what happens to them when they face moral and political crises,” Frankel says by way of explaining his attraction to High Noon’s tale of conscience versus compromise. “In the places I went to as a foreign correspondent — Israel, South Africa, Northern Ireland — people were confronted by history and had to make tough and personal decisions. I could tell that the Blacklist fit this criteria.” Frankel describes how the corrosive Cold War politics of the 1950s pervaded every aspect of High Noon’s production, which coincided with the peak of Blacklist-induced hysteria in Hollywood. With a conservative leading actor (Gary Cooper), a liberal producer (Stanley Kramer) and an erstwhile Communist screenwriter (Carl Foreman, who was called to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities during the film’s shoot), High Noon had as much drama off set as on screen.

While writing the book, Frankel was alert to the then-and-now parallels between the Red Scare and the Tea Party, both of which he characterizes as backlash movements driven by a dispossessed Right and directed toward left-wing “subversives” (whether communists or coastal elites). However, Frankel could not have predicted the book’s resonance in the Trump era. “The similarities are, unfortunately, the gift that keeps on giving.”

Rebecca Prime ’96 is a film historian and author of Hollywood Exiles in Europe: The Blacklist and Cold War Film Culture.

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu