A Core cornerstone undergoes its first major change in decades.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

A Core cornerstone undergoes its first major change in decades.

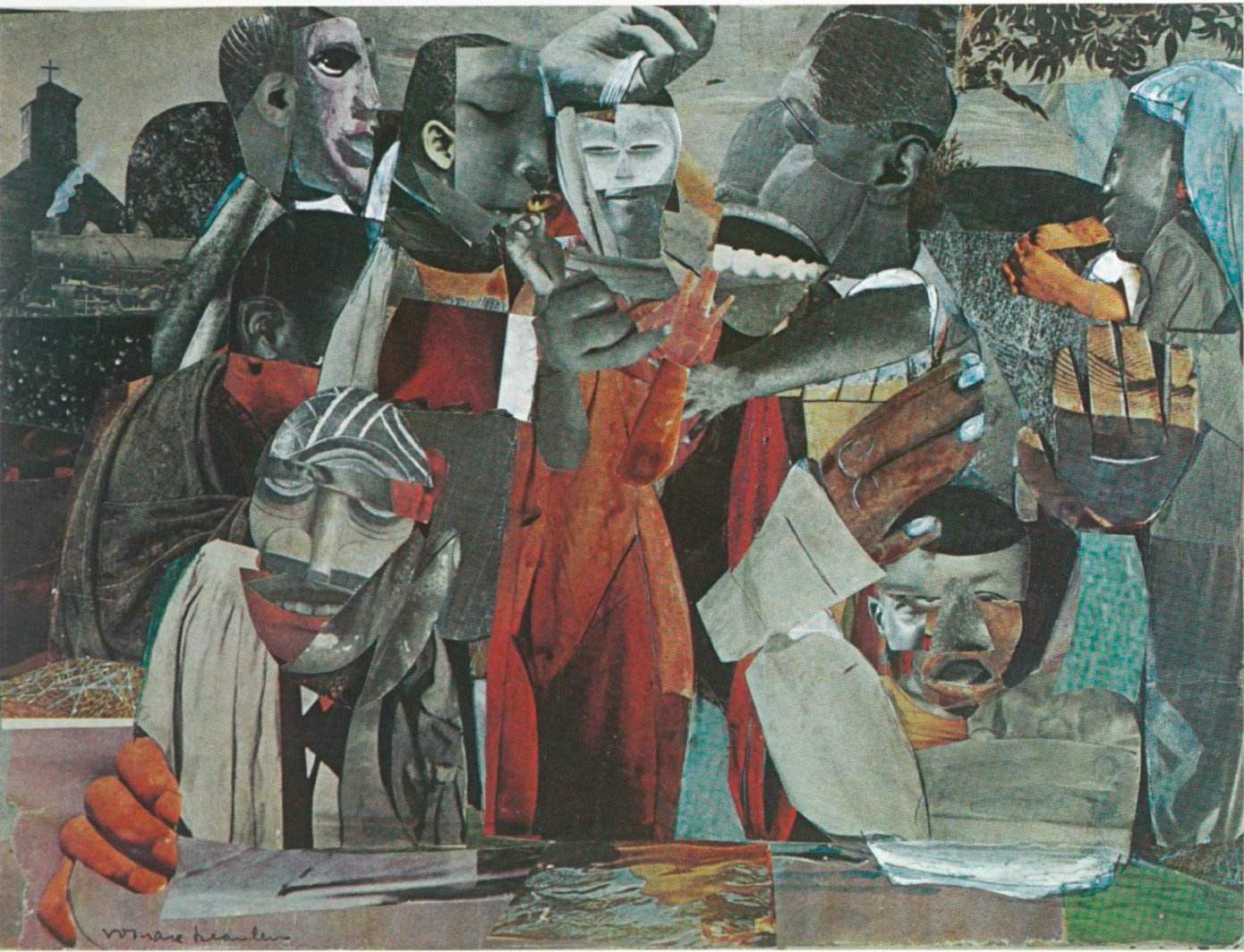

Romare Bearden is among the artists added to the Art Hum syllabus; his work includes the 1964 collage The Prevalence of Ritual (Baptism).

The new approach reflects the imperative of a more contemporary perspective, and is headlined by a notably more inclusive syllabus. Associate Professor Noam Elcott ’00, the former Art Hum chair who championed the review process, says the newly diverse roster has helped to cast the whole course in a different light.

“When I took over as chair [in 2018], there was not a single woman artist or a single artist of color on the syllabus,” Elcott says. “Today, the majority of units feature one or both. Collectively, the units of Art Humanities are now better able to bridge the gaps of time and space to interrogate vital questions of our presents and open essential windows into our pasts.”

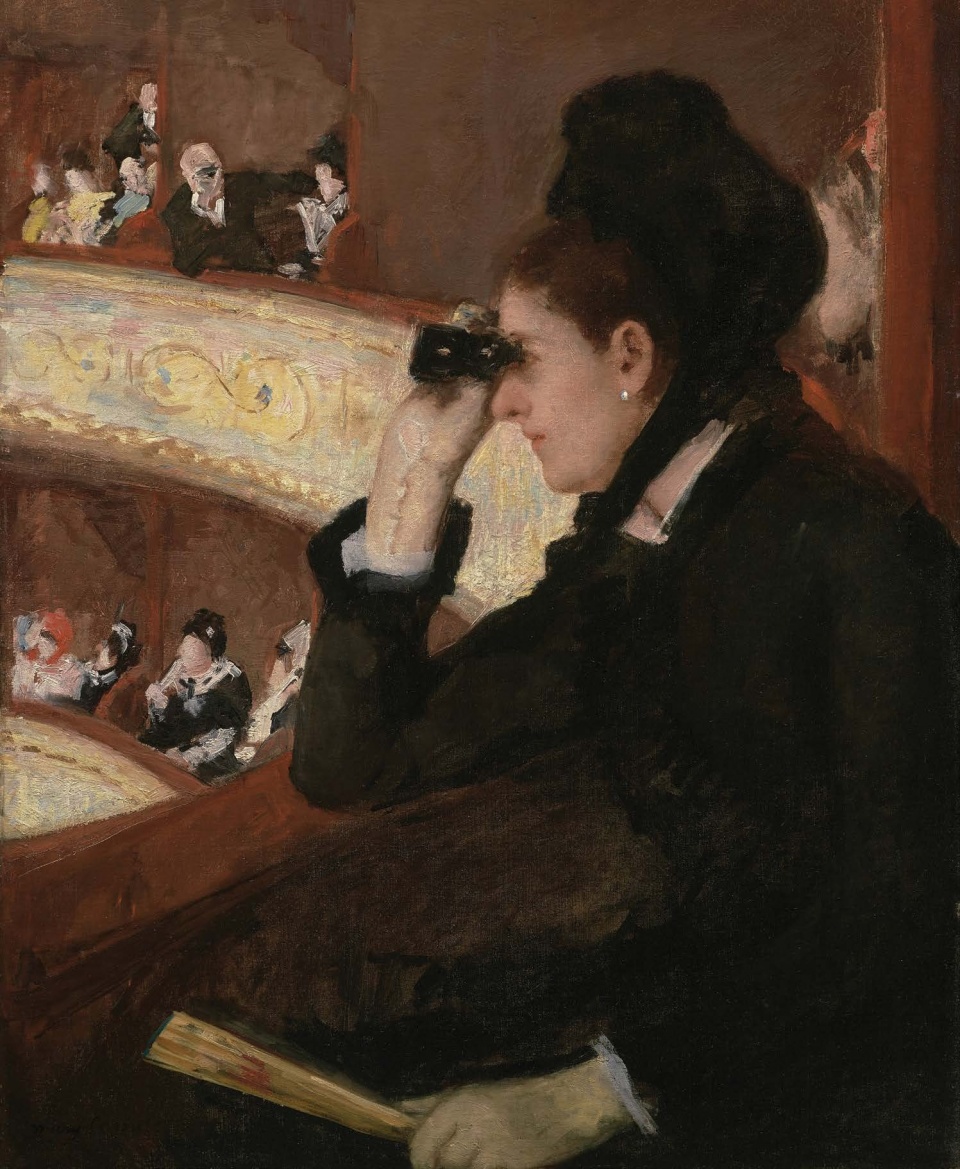

The addition of nine artists — some well-known, some more obscure — has opened entirely new avenues of discourse on subjects such as gender, race, family life, identity and access to education. New to the syllabus are Sofonisba Anguissola, Luisa Roldán, Clara Peeters, Angelica Kauffman, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Romare Bearden, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Cindy Sherman.

Significantly, greater diversity allows instructors to ask questions that take other viewpoints into account: “Previously, the question of the male gaze and the female nude was thematized in the course, but there were no women artists to offer the reverse,” Elcott says. “The story is vastly more complex and interesting the moment we add female painters.”

Along with changes to the “Art” aspect of the course, Zoë Strother, the Riggio Professor of African Art and the Jonathan Sobel & Marcia Dunn Program Chair for Art Humanities, says that boosting the “Humanities” part has been a major ambition of the reform. “We are prioritizing the big questions that concern us today, and doing a better job of engaging critical issues of contemporary relevance,” she says.

To best achieve that, Art Hum instructors meet five times a year for a seminar that operates like a quasi-think tank; participants and prominent guests discuss how to connect with students about the challenging issues that are transforming visual culture. “We used to just have content lectures that had nothing to do with what was happening in the classroom or the world,” Strother says. The seminar complements a weekly course designed for first-time instructors, which has been reformatted to focus on pedagogy. “This new style of briefings is working really well; I’m hearing a lot of compliments.”

A third component of the Art Hum update is regular syllabus review. “It’s now contractual that there is reform every three years,” Strother says. “We’ll no longer be fossilized. The changes might not be as radical, but it will keep the syllabus alive and help us continue to tinker with it.” The next review will begin this year and go into effect in 2023.

Reflecting on the effort that went into the change, Elcott pointed to the graduate students and faculty who thought outside the box and outside their comfort zones to reimagine Art Hum. “The goal was not to create a new canon, but to rethink what we could do with the course,” he says. “What’s great is that many people feared that by sidelining the question of canon we’d lost the thread that connects all of the units. But it’s been quite the contrary — we now see a much richer and complex braiding of art and history from ancient times to the present.”

Here, we’ve put together a guide to some of the new artworks, detailing how they broaden and enrich the student experience of Art Hum.

Though Anguissola may be largely unknown, she was in fact the most important female artist of the Renaissance. While contemporaries like Raphael were focused on portraying idealized types, Anguissola painted actual people, with a greater sense of realism. As demonstrated here, she was also a successful self-portraitist. “The question of self-presentation is brought into the mix in a manner that speaks obviously and immediately to a generation obsessed with selfies,” Elcott says. “Suddenly, we’re able to bridge the 500-year gap between the Renaissance and the present.”

Still Life with Flowers, a Silver-Gilt Goblet, Dried Fruit, Sweetmeats, Bread Sticks, Wine, and a Pewter Pitcher

Clara Peeters, 1615

Peeters, now being taught alongside Rembrandt, helped to introduce the still life as a significant genre of painting. “With the preponderance of food photos on Instagram, this is immediately recognizable to undergraduates,” Elcott says with a laugh. “It introduces a level of intimacy, of wealth, of showing off — she embeds self-portraits in reflections on the glasses and dishes.” The inclusion of exotic fruits and objects in Peeters’s paintings also expresses a nascent history of colonialism and slavery. “What look like benign objects carry the traces of the maritime powers of the 17th century,” Elcott says. “This prompts questions we weren’t able to ask previously.”

Zeuxis Choosing his Models for his Painting of Helen of Troy

Angelica Kauffman, 1778

Kauffman was a successful portraitist and also a history painter, which Elcott says was exceedingly rare at the time. This work tells the story of the Greek painter Zeuxis, who in order to portray the world’s most beautiful woman, synthesized parts of five models into an ideal whole. In Kauffman’s version, one model has snuck behind Zeuxis and grabbed a paintbrush, turning toward Zeuxis’s empty canvas. What does it mean for a woman to hold the brush, rather than be the object of idealization?

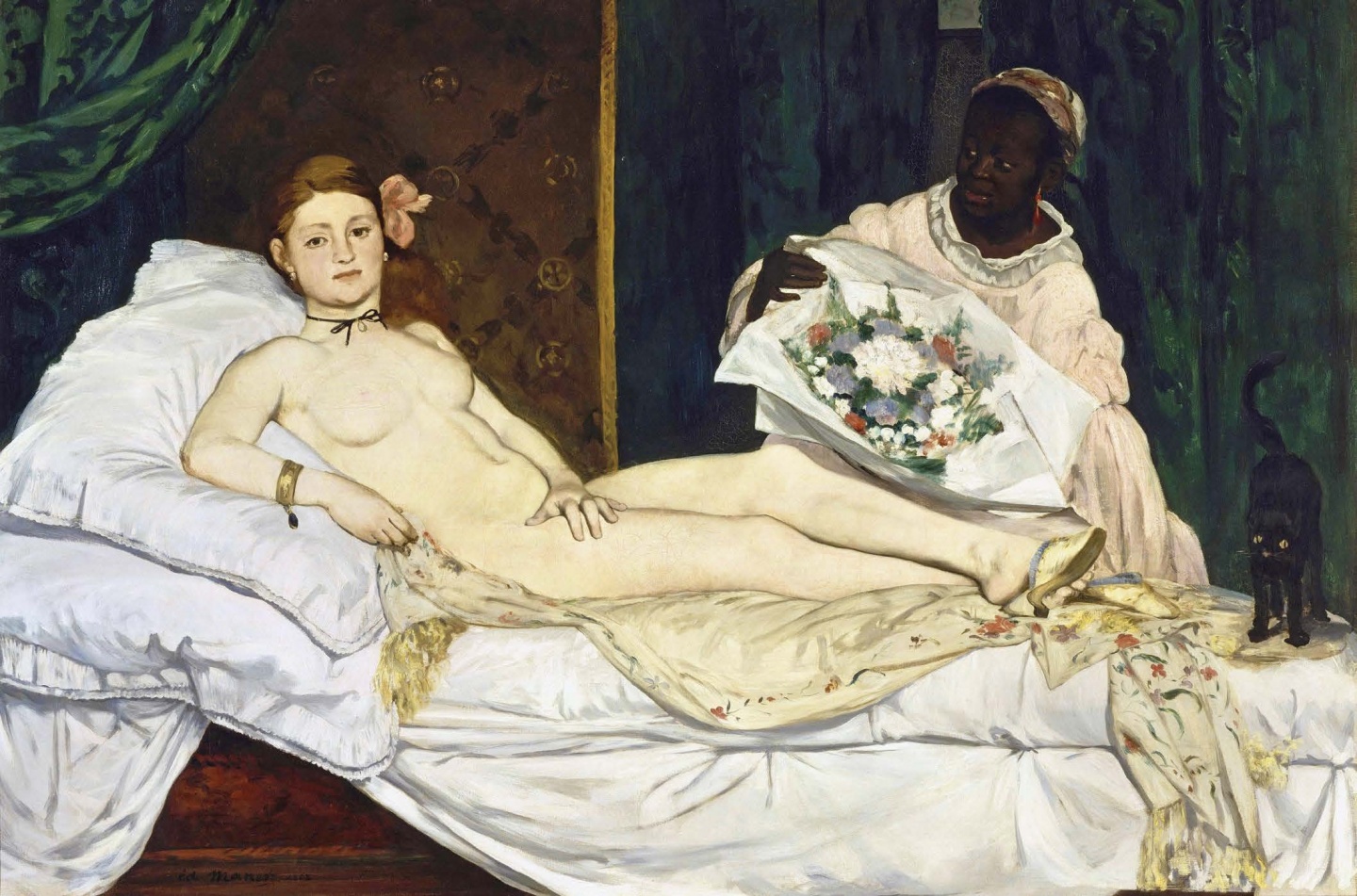

Morisot, a mainstay of the Impressionist movement, portrays home life for the first time in Art Hum. “We see her representing her mother and sister, in an intimate, private, domestic world in which men were not allowed,” Elcott says. “In 19th-century French and English, the phrase ‘public woman’ was a euphemism for a prostitute — the women in Éduoard Manet’s paintings are often assumed to be prostitutes or at least hold that potential. Morisot, by contrast, represents private women, and it’s a realm that we had no access to before the curriculum reform.”

Les Demoiselles D’Avignon

Les Demoiselles D’Avignon

Pablo Picasso, 1907

Kru Mask

1910

The Prevalence of Ritual (Baptism)

Romare Bearden, 1964

Kru Mask

The Prevalence of Ritual (Baptism)

Olympia

Éduoard Manet, 1863

Untitled (Maid from Olympia)

Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1982

Olympia

Untitled (Maid from Olympia)

In the Loge (At the Opera)

Untitled Film Still #54

Cindy Sherman, 1980

In this Cassatt painting, a woman is absorbed in the spectacle on stage, but a man in the background peers at her, and by extension, at us. “If ever there were a painting that complicates the male gaze and the female gaze, surely it is this one,” Elcott says. “This long trajectory of self-portraits [that consider] the male gaze, a woman’s role in society, and the private versus the public, is picked up again with the only living artist in the course, Cindy Sherman.” Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, a set of 70 photos that feature the artist in the guise of generic female movie characters, creates conversation about stereotypical portrayals of women.

Untitled Film Still #54

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu