|

|

|

|

|

FEATURESLike Frances Perkins, Thurgood Marshall and Sandra Day O’Connor, James E. McGreevey ’78 is An American FirstBy Dan Fastenberg ’05

"At long last, I publicly accepted my long-held private truth,” James E. (Jim) McGreevey says during a recent interview, when asked about his August 12, 2004, coming out as a “gay American,” an announcement that made him the first sitting governor in the history of the United States to openly embrace his homosexuality. “McGreevey’s use of the term ‘gay American’ was brilliant,” says David Eisenbach ’94, a lecturer in the Core Curriculum at the College and the author of Gay Power: An American Revolution. “The movement for gay rights only gained strength when it began — in the 1960s — co-opting the language of the country. By saying, ‘We’re Americans too, we deserve the same freedoms,’ you force the opposition into a place where they become un-American. When McGreevey used that phrase, it connected to this tradition.” Yet, unlike those other trailblazers mentioned earlier who by advancing themselves professionally were pioneering for their respective identities, McGreevey spent the first 47 years of his life hiding his. In a story that has been shared on Oprah Winfrey’s couch and has reached The New York Times bestseller list with the memoir The Confession (co-authored by David France), McGreevey’s embrace of his identity came about on much more ignominious terms: Only after trying to hold together a scandal-ridden administration did McGreevey finally come forward. Named after his uncle who died on the beaches of Iwo Jima during World War II, James Edward McGreevey was born in Jersey City, N.J., on August 6, 1957. McGreevey is the first child of Jack McGreevey, a regional director for the Time-DC trucking company and a veteran of World War II and the Korean War, for which he served as a drill sergeant, and Veronica (Ronnie), a registered nurse who still teaches nursing at the Muhlenberg Regional Medical Center School of Nursing in Plainfield, N.J.

McGreevey visits with President George W. Bush on June 24, 2002, six months into his term as governor. PHOTO: Jennifer Caruso, director of photography, Office of the Governor

Five years after the birth of their son, who was followed by two daughters, the McGreeveys relocated their family to Carteret, N.J., a working class suburb in Middlesex County. After finishing kindergarten at Pvt. Nicholas Minue Elementary School, McGreevey enrolled the following year at St. Joseph’s Grammar School, starting an uninterrupted run at parochial schools until his transfer to Columbia for the spring semester of his sophomore year. At St. Joe’s, McGreevey was taught to live a “Christ-centered” life, a view he abides by to this day. At 9, he became an altar boy at St. Joe’s and even began considering the priesthood for a career, an ambition he has returned to after all the political upheaval. In September, McGreevey will begin studies at the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan to become a reverend in the Episcopal Church, which he formally joined after a gradual falling out with the Catholic Church that began when the church refused to grant McGreevey communion upon his first divorce and active support of free-choice policies. Dreams of political glory, however, soon clouded the picture for the young McGreevey; at 13, he became an outspoken member of the silent majority, railing against the growing anti-Vietnam movement. At that time, his only criticism of Richard Nixon was about the decision to reduce raids across Vietnam’s 20th parallel in October 1972, a view McGreevey proudly announced during his high school debate class. “When I speak to my teachers as an adult, they joke and say the only reason I became a Democrat was because I couldn’t go any further to the right,” McGreevey says with a laugh. Waxing more contemplative, however, McGreevey looks back in his memoir and wonders whether he “felt back then that walking the conservative line would him keep [him] on the straight and narrow” as he became more aware of his homosexual feelings. And even though McGreevey speaks with nothing but warmth for his parents and the many other characters who populated his childhood, he also notes that his “entire personal identity was impeded during [his] childhood.” Graduating as a member of the National Honor Society from St. Joseph’s H.S. in Metuchen, N.J., McGreevey considered attending Saint Louis University, a Jesuit seminary in Missouri, in order to pursue a career that could purge the “evil” he felt was within him. Doubting his abilities to completely devote himself to the cloth, however, he chose instead to matriculate at the Catholic University in Washington, D.C.

McGreevey pays his respects at a Memorial Day event, May 25, 2002. PHOTO: Jennifer Caruso, director of photography, Office of the Governor

Studying in the nation’s capital exposed McGreevey to a different bureaucracy, one he wanted to become a part of; he recalls in his memoir sneaking into a Capitol Hill hotel on election night in 1976 to listen to Gerald Ford’s concession speech. Deciding that Catholic fell short in preparing future statesmen, and after picking up additional college credits at Rutgers and Middlesex County College, McGreevey successfully applied for a transfer to Columbia, which he began attending during the spring semester of 1977. “I was very much a part of it, the only way you can be at Columbia. I was there to learn,” McGreevey says about transferring. His time at Columbia, which he sped through in just three semesters and one summer term, was treated as an incubator for public life. “He was smart, to begin with, but you can also sort of see people that are intense and really want to know stuff and pay attention all the time,” recalls Richard Pious, the Adolf S. and Effie E. Ochs Professor of American Studies at Barnard, whose course on the American presidency McGreevey took. McGreevey also warmly recalls his Art Humanities professor, Richard Brilliant, for his patient stewarding of his prose, and his political science adviser, Andrew Nathan, whose lessons on Chinese politics have proved valuable to McGreevey a generation later in his representation of Kean University in negotiations to open a branch in China. Since November 1, 2006, McGreevey has been an “executive in residence” at Kean, where he also teaches law and ethics. “I read books that touched my life, with the professors who gave me the capacity to answer the critical questions relating to governance,” McGreevey says of his College education.

McGreevey, NBA Commissioner David Stern (right) and basketball Hall of Famer Willis Reed (left) read to students as part of the NBA’s “Read to Achieve” initiative. PHOTO: Jennifer Caruso, director of photography, Office of the Governor

And even though Columbia provided McGreevey with a chance to live in an environment not dictated by church dogma, he chose to associate himself with Roman Catholicism as much as possible in Morningside Heights. “Columbia at the time was among the most-gay friendly colleges in the United States, but I could never cross that threshold,” McGreevey says. McGreevey requested housing at Ford Hall, the on-campus residence intended for Catholic graduate students that was administered by the Catholic Chaplaincy. Immersed in the Catholic community, McGreevey came across the National Catholic Reporter and the contributions of then-Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador. McGreevey says Romero’s descriptions of life in the Central American country, then under the grips of a brutal military regime famous for its death squads, helped steer him to become a Kennedy Democrat. When the Reagan administration began increasing support for El Salvador’s military junta in the name of Cold War politics even after Romero was assassinated, McGreevey formally changed his party affiliation.

McGreevey made New Jersey the second state in the country to invest in stem-cell research, opened a 24-hour hotline for reporting child abuse and signed the environmentally-conscious Highlands Act.  But before McGreevey began his career in Democratic New Jersey politics, he picked up two more degrees, a J.D. from the Georgetown Law Center in 1981 and a master’s in education from Harvard in 1982. In order to help finance his education, for which he had saved money by finishing college in just three years, McGreevey enrolled in Georgetown’s night program, which allowed him to work part-time during the day, including a stint reviewing tax appeals at the Department of Justice. On top of all that, McGreevey volunteered with the “street law” program, teaching civics to students at Gonzaga College H.S. in Washington, D.C. He even began to lay the groundwork for a political career in New Jersey by volunteering for Democratic Congressman Bernie Dwyer in his 1980 reelection bid. Despite all those activities, McGreevey maintained his work ethic when it came to his studies. Jonah Shacknai, a law school classmate and the chairman and CEO of the Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp., remembered one course in which McGreevey stood out because he was “the only one who had the time and patience to master the minutiae of medieval property transfer rights.” After finishing his coursework, which also included a summer program at the London School of Economics through the Notre Dame Law School and concluded at Harvard, where he focused on theories relating to early education, McGreevey settled back home in Carteret, primed to enter the political fray. “I was a young man in a hurry, there’s no doubt about it,” McGreevey says. McGreevey’s first stop was a year at the prosecutor’s office of his home county, Middlesex, where he was hired to work in the juvenile division and was mostly assigned to cases relating to drug dealing. Through canvassing the local political circuits, McGreevey got his first political break. Attending a dinner in 1983, he was offered a job as an aide to Alan Karcher, at the time the speaker of the New Jersey General Assembly, the lower house of the New Jersey state legislature. After focusing in the assembly on issues relating to elder care, where he helped pass legislation protecting seniors from being carelessly evicted from their nursing homes, McGreevey landed a job in 1985 as the executive director of the state parole board. Championing the rights of victims, McGreevey gained his first entry onto the national stage. Writing on the November 16, 1986, editorial page of The New York Times, McGreevey noted that in New Jersey “parole cannot be considered without reviewing and considering the input of the victim,” a progressive stance at the time.

McGreevey speaks at a fundraiser for the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, September 23, 2002. PHOTO: Daniel Brennan, Office of the Governor

McGreevey moved to the private sector in 1987, becoming a regional manager for public affairs at Merck. Working as a government lobbyist, McGreevey used the position as a base to begin his first foray into elective politics. With the 1989 New Jersey governor’s race looming, Karcher, McGreevey’s former boss in the assembly, vacated his seat as state assemblyman to make a run for the governor’s mansion, putting the 19th legislative district in play. McGreevey wasted no time, winning the race to succeed Karcher, but only after enlisting the help of the New Jersey political machine. Upon arriving in Trenton, while still holding onto his job at Merck, McGreevey used his considerable energy to spearhead legislation requiring insurance packages to include coverage for mammograms. Meanwhile, he took further steps he felt were necessary for his political career. Vacationing on a cruise to Bermuda, McGreevey met and courted Kari Schutz, a librarian from British Columbia. They married in 1991, and had a daughter, Morag, the following year. “I don’t think my homosexuality was an open discussion. It was there, but I had made a decision in adolescence that the closet was the more sensible place to be. Public office only fortified the correctness of my decision, which I now know was the wrong course,” McGreevey says. McGreevey’s next move came at the expense of a former confidant. Then-Woodbridge mayor JoJo DeMarino had been an enthusiastic backer of McGreevey’s run for the assembly in 1989 but soon thereafter found himself embroiled in a bribery scandal. McGreevey, facing a threatening redistricting, showed he was willing to play hardball by challenging DeMarino for mayor of Woodbridge and adopting the campaign slogan of “the unindicted Democratic ticket” en route to winning the election. Taking office on January 1, 1992, McGreevey remained mayor of the state’s fifth largest municipality until the moment he became state governor, on January 15, 2002. During his tenure, McGreevey won two reelections, in 1995 and 1999, thanks in part to restoring fiscal accountability to the township. DeMarino had left its books in shambles; two federal agents showed up at the mayor’s office on McGreevey’s second day at work asking for $650,000 in missing health insurance funds. Through borrowing, some of which came in exchange for Republican support in the Municipal Council, McGreevey erased the $24.5 million budget gap by the time he decided to challenge then-governor Christine Todd Whitman in her 1997 reelection campaign. Further polishing his resume, McGreevey already had become state senator for the 19th legislative district in the 1993 election, winning the seat in a particularly bad year for New Jersey Democrats. The increased obligations, however, were too much for McGreevey’s wife, and she began divorce proceedings in 1995, complaining of McGreevey’s obsessive work habits. By 1997, Whitman was being touted as a rising star in the Republican Party; the idea of her becoming a future part of a national ticket was even being mentioned. McGreevey, however, fearlessly took her on, trying to paint her as a stooge of the super-rich who had allowed auto insurance rates to balloon. In a race that attracted national attention, McGreevey nearly toppled the Whitman machine, coming up just 26,000 votes shy, a one percent difference in a race in which more than two million votes were cast. It was McGreevey’s first, and only, campaign loss.

McGreevey’s memoir, The Confession, made the best-seller lists upon publication last year.

During the ’97 campaign, McGreevey met Dina Matos, a Portuguese immigrant more comfortable with a political life. They married in October 2000 at the Hay-Adams Hotel in Washington, D.C., on a terrace overlooking the White House. Having come so close to becoming governor, McGreevey was not about to stop there. He made no attempt to hide his ambitions, telling The New York Times the day after the ’97 race he would “most probably” run again in 2001. True to his word, McGreevey spent the next four years building support for the next gubernatorial race, demonstrating a Clintonian devotion to retail politicking with pit stops at nearly every interest group imaginable, from Holocaust survivors to a continued commitment to the New Jersey political machine. By Election Day 2001, Whitman had left Trenton to become administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President George W. Bush. Running against a more conservative opponent, Bret D. Schundler, McGreevey aimed for the political middle, championing support for public education, defense of abortion rights and reform to the “pay to play” nature of New Jersey politics, in which government no-bid contracts are awarded to campaign contributors. He won easily, by 14 percentage points. However noble his intentions, McGreevey’s administration was doomed even before his inauguration. On a political trip to Israel in 2000 sponsored by the United Jewish Federation of MetroWest, a grouping of New Jersey counties, McGreevey met Golan Cipel, then the spokesman for the mayor of Rishon Lezion, an Israeli city near Tel Aviv. Cipel agreed to relocate to New Jersey to help McGreevey’s upcoming gubernatorial campaign, working on outreach to the Jewish community. McGreevey alleges a consensual relationship with Cipel began at the time his campaign wound down, made easier by McGreevey’s wife’s extended hospital stay stemming from complications from the birth of her first and McGreevey’s second daughter, Jacqueline, on December 8, 2001. Cipel, interviewed for this article, denies the consensual nature of the relationship, claiming he was the target of unwanted and overly aggressive sexual advances. “My story was just the tip of the iceberg. Here’s a guy who was involved with so much corruption,” Cipel said in a telephone interview. “Every thing he touched was a disaster.” Even before his January 15, 2002, inauguration, McGreevey’s political universe was collapsing. Several scandals emerged, including an FBI sting of McGreevey’s fundraising tactics, a bizarre incident during which the governor was caught using the word “Machiavellian” (McGreevey claims the use of the word was coincidental, and that it was not a code word). But it was the relationship with Cipel that would prove McGreevey’s undoing. In the aftermath of 9-11, McGreevey’s decision to appoint Cipel as a special counsel for homeland security with a $110,000 salary at a time when the state was having budget difficulties came under immediate fire. Both sides could point to reasons to either support or oppose the appointment; McGreevey cited Cipel’s experience as a member of the Israeli Defense Forces and as an employee at the Israeli consulate in New York, while critics, led by Republican state senator Charles Gormley, questioned the nature of the men’s relationship and just how substantive Cipel’s experience had actually been.

Since leaving office, McGreevey has resurrected that serious-minded political activism, applying his work ethic to issues relating to poverty and the notoriously high rate of suicide among gay teens.  McGreevey tried to control the uproar, famously telling The Bergen Record on February 20, 2002, that Cipel was “uniquely qualified” for the position, even though former FBI Director Louis Freeh had offered his services for free. But after the FBI refused to allow Cipel the security clearance he needed to conduct his job because he was not a U.S. citizen, the appointment became untenable. Cipel was reassigned to other duties within the administration and resigned in August 2002, eight months after he and McGreevey had begun working for New Jersey. “McGreevey might have been forgiven if he had assigned Golan Cipel to an insignificant cabinet job. But to trifle with the security of the state most seriously affected by 9-11 was unforgivable,” Rutgers University Professor of Political Science Ross K. Baker says. “I honestly believe that if all he had done was declare his sexuality, he could certainly have held on to the governorship.” During an interview on September 26, 2006, moderated by New York Times reporter Patrick Healy at the New School University, McGreevey directly answered charges that his sexuality was presented as a smokescreen to avoid confronting other scandals. “No one in my government was ever charged, or indicted, or convicted. No one … I resigned simply and categorically for the reason I resigned,” he said. Before he left office, and with the Cipel situation temporarily under control once Cipel left government, McGreevey was able to devote his energies to several initiatives. He made New Jersey the second state in the country to invest in stem-cell research, opened a 24-hour hotline for reporting child abuse and signed the environmentally-conscious Highlands Act, protecting the 850,000 acres of the Highlands region in northern New Jersey from development. He also worked to improve the E-ZPass electronic toll collecting system, decreasing the number of inaccurate violations levied, and in his last hour before stepping down, pushed through landmark legislation making it illegal for government contractors to donate to campaigns, an attempt to combat the “pay to play” system. And in January 2004, the still-closeted, and still-married, McGreevey signed a domestic partnership law, making New Jersey the fifth state in the country to establish a form of recognition for partnerships regardless of gender. “I was never anti-gay,” he says. “I was envious, almost jealous of people who found the courage. But I wasn’t going to take it out on them.” McGreevey has since stated he regrets his earlier stance against gay marriage, which he now supports. But McGreevey will never be remembered as the governor who pioneered for gay rights, but rather, as the gay governor, and for the ensuing resignation. When he received word on July 23, 2004, that Cipel was going to sue him for sexual harassment, McGreevey decided to go public, which he did 19 days later. “While it was most definitely a political decision, my decision to resign was an attempt to do the right thing,” he says. His legal problems quickly evaporated when Cipel soon thereafter decided not to proceed with the charges. “McGreevey definitely will have a big place in the history of the gay rights movement,” says Gay Power author Eisenbach, who hosted a book signing for McGreevey at Faculty House on October 20, 2006. “One of the great successes of the gay rights movement has been presenting the public with a new image of being gay, as opposed to the silly characters you see on Will & Grace. His coming out was a public moment when people saw that gays can also be seriously minded and politically active. How else can you get Oprah to discuss the issue without having a public figure facing the issue in such a public way?” Since leaving office, the consequences of McGreevey’s long-standing choice to prioritize a public identity over all else linger in the public sphere. The ongoing custody battle over his second daughter with his second wife, Dina Matos, is regular fodder for the national media, still fixated on the scandal some three years on. In May, Matos received considerable attention when her book, Silent Partner: A Memoir of My Marriage, was published. In it, she refutes her estranged husband’s allegation from their divorce papers that she “knew of his sexual orientation” before they got married.

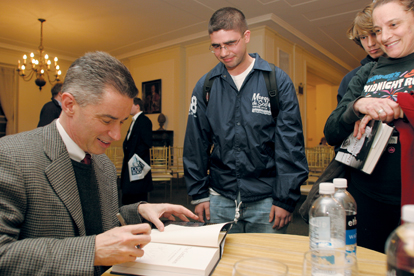

McGreevey spoke at an event in Faculty House on October 20, 2006, and later autographed copies of his memoir. PHOTOS: Malcolm Linten  As far as he is concerned, however, McGreevey may very well be more removed from the events of 2004 than the media is. Since leaving office, he has resurrected that serious-minded political activism, applying his work ethic to issues relating to poverty and the notoriously high rate of suicide among gay teens. “I can now focus on issues for which I have passion,” he says, without even pausing before spreading his message. “People need to know that being gay is not a choice. And people need to know that while religious institutions provide a sound moral grounding, rigid orthodoxy of any faith produces bad results.” McGreevey says he is now leading an “integrated life,” having moved with his partner, Australian financier Mark O’Donnell, into a stately colonial in Plainfield, N.J. His championing of gay rights has been apparent from his frequent contributions to The New York Times’ letters page. Russell Shorto’s April 8, 2007 article in The New York Times Magazine entitled “Keeping the Faith,” about Pope Benedict’s attempt to reinvigorate Europe as a Christian land, was one article that caught McGreevey’s attention. In a letter published on April 22, McGreevey noted, “It would seem problematic for the church to advocate for the inclusion of a religious viewpoint within the European cultural debate but be unwilling to suffer dialogue internally on issues of the day, including abortion, priestly celibacy, gay rights, etc.” Yet, McGreevey did not immediately throw himself back into political activism. After the resignation, the chronic workaholic made sure to take some time to first do some soul searching. “I still go back to the books of the Core Curriculum,” he says. “Those books are timeless. They still speak to us today, across the chasm of history. But for whatever reason, man keeps making the same mistakes.” Dan Fastenberg ’05 is a night editor at the international news desk at the Buenos Aires Herald in Argentina, where he teaches business English through the Interaction Language Institute. He profiled Rep. Jerry Nadler ’69 in the May/June 2006 CCT.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||