|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COLUMBIA'S 250TH ANNIVERSARY250 Years: Columbia College, 1754-2004An Inner Life of Sufficient Richness - From General Honors to Literature Humanities.

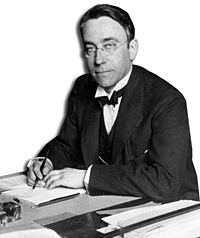

In the November 2003 issue of Columbia College Today, Queen Wilhelmina Professor of Dutch History J.W. Smit discussed the origins of “Contemporary Civilization,” the original Core course that was created in 1919. Many may not realize, however, that the Humanities sequence — Literature Humanities, Music Humanities and Art Humanities — which was formally established in the late 1930s, has nearly as long a history. Beginning with an unprecedented General Honors course in 1920, Columbia gradually developed the three humanities courses that all College students take today. In this excerpt adapted from An Oasis of Order: The Core Curriculum at Columbia College (Columbia College, 1995), Timothy P. Cross ’98 GSAS recounts the curricular and social developments that prompted the College to create its humanities courses. Cross, who earned a master’s degree and doctorate in European history from Columbia, has taught in the Core Curriculum frequently since 1990. He wrote An Oasis of Order as part of the 75th anniversary celebration of the Core Curriculum. Cross is director of electronic programs in the Alumni Office and a contributing editor to Columbia College Today. The full text of An Oasis of Order is available online: www.college.columbia.edu/core/oasis/. By Timothy P. Cross ’98 GSASWhile faculty in the social sciences were collaborating in the creation of the Contemporary Civilization course, the humanities at Columbia were beginning their own revolution. Under the incessant prodding of Professor of English John Erskine (Class of 1900), in 1920 the College instituted an optional two-year General Honors course, built around “great books” read in translation and discussed in small groups. Although no one seems to have realized it at the time, this proved to be the first decisive step toward the creation of the second main pillar of Columbia’s Core program — the Humanities sequence. As with CC, the chain of events that led Erskine to push for the General Honors course went back before World War I. In fact, many of the same issues that encouraged the creation of CC also contributed to this humanities course. Looking back, Erskine traced the genesis of his course to a widespread concern within the faculty about “the literary ignorance of the younger generation.” In particular, many faculty believed that students rarely, if ever, read truly classic texts: “the Bible, or Homer, or Vergil, or Dante or the other giants whom the world at large have long esteemed.” Ideally, it was thought, a college education would be a perfect remedy for this problem, but the Columbia curriculum — especially the tendency toward professional and academic specialization — and the rush toward degrees did not encourage this kind of reading. The older, gentlemanly ideal of being “well read” was hardly mentioned at all.

Erskine had a solution. As he later recalled, “If the faculty believed that the boys in college ought to be familiar with more than the titles of great books, that happy result could be achieved in a new kind of course, extending through two years, preferably the junior and senior years, and devoted to the simple principle of reading one great book a week, and discussing it in a weekly meeting which would last two or three hours.” This was an idea whose time had come. In 1891, George Edward Woodberry, a Harvard graduate who taught at the University of Nebraska and edited The Nation, was appointed to a comparative literature chair at Columbia. For Woodberry, “literature was life itself,” and in both his writings — especially Great Writers (1912) — and his literature courses at Columbia, he championed reading great books. Erskine emerged as one of Woodberry’s most brilliant pupils, and when he returned to Columbia after World War I, Erskine applied his teacher’s ideas in the General Honors course.

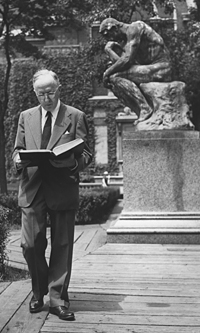

In concentrating exclusively on classic texts, the course marked a new approach, but Erskine’s real innovation was to “treat The Iliad, The Odyssey and other masterpieces as though they were recent publications, calling for immediate investigation and discussion.” Not only did this mean reading works in translation, which was bad enough for many of his colleagues, but also reading them outside of traditional academic disciplines. In Erskine’s plan, students would read and discuss each book rather than being introduced to it in lectures and through secondary sources. In fact, although the plan was to teach “classic” texts, General Honors was actually a reaction against the empty classicism of many contemporary liberal education programs. While Greek and Latin texts were to feature prominently in the General Honors course, the Greek and Latin were relatively unimportant — it was ideas that mattered. While few denied that reading many classic works in translation was inevitable, even for the highly educated, many still felt that reading in translation was incompatible with true scholarship. And there were other, more serious objections. One professor wrote privately to Dean of the College Frederick Keppel, voicing the common concern that “such an ambitious program like this can lead only to a smattering of knowledge, and not to a real understanding of any one author.” The College, this critic continued, “should stand for exact knowledge of a few things rather than for superficial acquaintance with many things.” Erskine’s response was devastating in its simplicity. Every book, he noted, had to be read for a first time, and there was a profound difference between a humane familiarity with great authors and an academic exploration of them. Discussions took place within the faculty during 1917, and they had agreed to offer (though not require) this course when America’s entry into World War I interrupted all plans. Erskine went to Europe to help educate American soldiers, the College geared up for war and the great books course was put on hold. When Erskine returned to Columbia in 1919, he pressed again to begin the course, and in 1920 he received permission. Although in later years Erskine gave the impression that Columbia’s faculty suffered his plan rather than supported it, the number of dedicated and energetic instructors who taught the course in the 1920s suggests that his may not have been such a solitary voice. In the first year of General Honors, Erskine was joined by Mortimer J. Adler ’23, Raymond M. Weaver, Emery E. Neff, Mark Van Doren, H.W. Schneider, Rexford G. Tugwell, Arnold Whitridge, Henry Morton Robinson, Clifton Fadiman ’25, Irwin Edman ’17, C.W. Keyes and J. Bartlett Brebner. By any standard, this was an impressive list. Adler would leave Columbia in the 1920s for the University of Chicago, where he would transform the curriculum along lines suggested by the General Honors course and begin his lifelong support of great books programs. Van Doren, of course, would stay at Columbia, achieving an unparalleled career of original poetry, prose, scholarship and teaching. But for the larger history of general education at Columbia, this list holds a different interest. Not only did many of these professors, still young men when they began teaching General Honors, go on to distinguished careers, but they later became instrumental in establishing the Humanities sequence in the 1930s. Nor was General Honors the only effort at general education for these men. Edman and Keyes were instrumental in establishing CC, and Brebner, a history professor, taught CC for many years. The economist Tugwell taught CC for much of the 1920s and early 1930s until he began to serve in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust” during the Great Depression.

One problem — perhaps the crucial problem — persisted: What constitutes a great book? This thorny issue proved the major impediment in 1917, when the course was first proposed, and the College’s Committee on Instruction came to no firm conclusion, preferring to let Erskine draw up a list of his own to see what happened. Although Erskine later admitted that it became easier to define a great book after the General Honors course had been given for a while, he had a few general ideas from the start about what books should be included. “A great book,” he said, “is one that has had meaning, and continues to have meaning, for a variety of people over a long period of time.” This did not mean that there would be a consensus about the meaning of a particular author since “the really great writers have been accepted by large groups of people for many different reasons.” Put another way, for Erskine, greatness came from richness and ambiguity; books were important not simply because people read them, even less because people agreed with them, but precisely because people often couldn’t agree about them — at least not completely. While the idea of studying great books had its most significant impact at Columbia, it quickly spread to other colleges and universities. This impact still is being felt. Erskine’s original reading list had approximately 75 books, ranging from classical antiquity through 1800. In the 1920s and 1930s, Columbia modified Erskine’s list — as did the University of Chicago, Notre Dame, St. John’s College and other schools that adopted great books seminars — but most later great books courses have kept about 85 percent of Erskine’s original readings. At Columbia, the General Honors course entailed a two-year program, with students reading one book each week. Classes met in sections of 25–30 on Wednesday evenings to discuss the work. Each section had two instructors, who were there to spur discussion and who, it was hoped, would not argue too much. As with CC, the crucial assumption was that discussion, not lectures, would lead to the desired result: an immediate appreciation of the works.

In the General Honors course, there was no attempt to limit the works to strictly literary texts, if by that we mean books read for their literary merits rather than for their religious, philosophic or scientific content. Students read Homer and Aeschylus, Dante and Shakespeare, but they also read the Bible, Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine and Spinoza. The inclusion of philosophers and theologians was perfectly consistent with the overall aim of the course, which was to produce educated men, not men with a strong literary background. General Honors was designed to provide an introduction to works that would repay frequent re-readings; it was the first step in a lifelong education. Here, the General Honors course adopted an outlook similar to that which animated CC, namely, that “the principal obligation of the College is to help develop the student into a more complete human being.” This wasn’t a course for everyone, however. It even embodied a not-too-subtle elitism since not all students participated, but only those who passed special examinations, received recommendations and demonstrated superior academic performance. Justus Buchler (chairman of CC in the 1950s) observed that General Honors threatened to create an “Honors aristocracy” among students at the College. Unlike CC, which caught all students as they entered the College, General Honors could only be a brass ring grabbed by a select few.

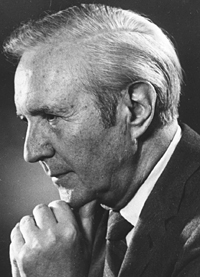

Erskine’s General Honors course was discontinued in 1929. 1 Nevertheless, interest in a great books course continued, and in 1932, General Honors was resurrected as the Colloquium in Important Books. The colloquium maintained several characteristics of the earlier course: small classes of juniors and seniors who were selected after interviews, reading one book a week, and then participating in Wednesday evening discussions moderated by two instructors. While Erskine supported this new colloquium, he only advised the three younger faculty members — Jacques Barzun ’27, James Gutmann ’18 and Weaver — who were in charge of planning it. Brebner was responsible for developing a new reading list, which was now extended to cover works from the 19th century. The plan called for four single-semester colloquia, each treating works from a particular historical period (antiquity, the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the 17th and 18th centuries, Romanticism and Modernism), with select juniors and seniors chosen for the course after interviews. Like General Honors, the Colloquium was designed to offer students “a program of reading worthy of their fullest and continued application” and would express “the delight of a cultivated layman.” But like General Honors, this colloquium wasn’t meant for everyone, for concerns about professional preparation asserted themselves in its planning. In some ways, the Colloquium represents a rather narrow scholarly enterprise: the desire to prepare would-be scholars for further study. As Gutmann observed, “Students of exceptional ability whose intellectual interests are in what is still called the liberal arts tradition have not always been equally well served” at the College as students pursuing careers in other disciplines. The Colloquium was designed to provide specialized academic training for future liberal arts graduate students, rather than for all students.

All in all, despite any similarities in staffing and interdisciplinary content, General Honors and the Colloquium embodied different ideals from CC. Both great books courses were designed for upperclassmen, not freshmen. Nor did either match the lofty goals of Contemporary Civilization: giving all students information valuable for life. Rather, both General Honors and the Colloquium resemble other attempts to give new educational outlets for above-average students, such as the Honors program developed by Frank Aydelotte at Swarthmore College in the 1920s. Nor did the later development of the Humanities sequence for freshmen eliminate the usefulness of an upper class great books course. For many, the absence of required humanities study for freshmen and sophomores left an important gap in the curriculum. For all its popularity, CC did not satisfy the hunger for general education at the College or offset the dangers of a curriculum still full of narrowly practical and specialized courses. In 1930, the educator Abraham Flexner (who had spent a year at Teachers College) noted that “a student at Columbia College may study serious subjects in a serious fashion. But he may also complete the requirements for a bachelor’s degree by including in his course of study ‘principles of advertising,’ ‘the writing of advertised copy’ … ‘business English,’ ‘elementary stenography’” and other less-than-liberal offerings. Flexner was hardly a typical critic, but there is no denying that worries about making a living could motivate students more than a any commitment to liberal education. Indeed, the urge to prepare for a career has remained a constant in American higher education, and Columbia students couldn’t be expected to deviate from this pattern without some encouragement.

Within the faculty, it was widely felt that a required course in the humanities would complement CC’s introduction to the social sciences and would reaffirm the College’s commitment to making men, not businessmen. The College did not rush to introduce the second great pillar of the Core program, however. Discussions about a humanities sequence began with the appointment of a committee headed by Edman in October 1934. Later, two subcommittees — one headed by Van Doren and another by John H. Randall ’18 — played major roles. As much as CC, the Humanities element of the Core Curriculum was the result of careful deliberation and the work of many faculty. 2 The original plan was to offer courses on literature, music and the fine arts in a single two-year course. “In the field of the Humanities, a student has no opportunity in the first two years of his college work to get a generalized picture of the relations of literature and the arts to each other,” stated a memorandum from the Edman committee, “and all of these to the civilization of which they are an expression.” Here, CC provided a crucial model: “A course in the Humanities would be designed to do for the field of arts and letters (including philosophy) something analogous to what Contemporary Civilization does for the social sciences.”

On September 23, 1937, the College began its new Humanities sequence designed specifically for underclassmen. The names of the courses were unimpressive. Humanities A, a yearlong course required of all freshmen, covered a series of classic texts of Western literature and philosophy from classical antiquity to the end of the eighteenth century. Humanities B, an optional course for sophomores, was devoted to the visual arts and music in the West. In 1947, Humanities B would become required, changing its name to Art Humanities and Music Humanities. Much later, Humanities A would become Literature Humanities. But these were changes in name only, for there is a fundamental continuity in the humanities courses that has persisted to the present. In 1937, however, the future was uncertain. Instructors approached their new enterprise with a mixture of enthusiasm and apprehension because while the idea of teaching humanities was appealing, there were real concerns about giving complicated material to “unselected and, so to speak, unprepared freshmen.” Difficulties in planning the course weighed heavily also. Well into 1936, the College still had hoped to fashion a single, two-year course that would cover literature and the arts from the ancient world through the 20th century, but practical problems — especially in the musical component — eventually obliged the College to require only the first year. As the required course in the sequence (and as the course required of freshmen), Humanities A received the greatest scrutiny. At heart, it wasn’t an attempt to replace or resurrect the earlier humanities courses, despite many similarities. After its first year, Barzun stated four crucial beliefs supporting the new course: “First, that a college granting the Bachelor of Arts degree should not merely pave the way to professional training, but should try to produce educated men. Second, that if educated men are those who possess an inner life of sufficient richness to withstand the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, they must have learned to feed their souls upon good books, pictures and music. Third, that the memorizing of labels, catchwords and secondhand judgments about art and books is not educative in any real sense. And lastly, that to know and to be at home with books a man must at some time or other read them for the first time.” Overall, Humanities A focused on important books read as humane texts rather than as adjuncts to courses in literature, philosophy, or history. The course emphasized that these books “address themselves primarily to man as man, and only secondarily to man as philosopher, historian or college undergraduate.” These assumptions combined the liberal civic-mindedness of John Howard Van Amringe (Class of 1860, former dean of the College) and John Coss (the first director of CC) with the humane and cosmopolitan aspirations of Woodberry and Erskine. Like the founders of CC, the planners of Humanities A recognized that the purpose of a college education went beyond preparing for a career. Like Woodberry and Erskine, the planners committed themselves to the study of important books that could provide the basis for discussions of the human experience. No one thought that Humanities A would exhaust these texts or satisfy the desires of students; instead, the emphasis was on, in Parr Professor of English Emeritus James Mirollo’s words, “introducing students to the critical reading and comprehension of a powerful and resonant work.”

Those planning Humanities A wanted students to purchase their books, for they believed firmly that “some books must be read alone, in bodily comfort, and at a sitting the length of which follows desire rather than the clock. Besides, books densely packed with ideas must be marked, underlined and annotated by the reader.” Nevertheless, to keep up with the heavy reading load, students would have to follow both desire and the clock. The reading list owed a great deal to Columbia’s earlier humanities courses, though it had somewhat fewer books because everything had to fit into one year. It emphasized Greek and Latin classics more than the earlier lists, not because any classical texts were added but because fewer were cut to create the one-year list. The fall semester concentrated exclusively on the heritage of Greece and Rome. From Greek culture, students studied epic (The Iliad), drama (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes) and philosophy (Plato and Aristotle). From Roman civilization, students read Lucretius, Vergil and Marcus Aurelius. In contrast to this deliberate march, the spring semester of Humanities A sprinted 1,500 years, from St. Augustine’s Confessions through Goethe’s Faust.

The Humanities A syllabus never was intended to represent a fixed canon of texts. Indeed, the College avoided describing Humanities A as a “great books” course precisely because of the unwelcome dogmatic associations that the phrase conjured up. As the College’s Committee on Plans observed, “What tradition suggests, when one comes down to it, is remarkably changeful.” And tradition did change. In 1938, selections from Herodotus and Thucydides were added to the fall reading list. In 1940, the Bible (the Book of Job) was belatedly added, the only non-classical text in the fall’s reading. By 1946, Tacitus had replaced Marcus Aurelius. There were changes in the spring semester as well. The Tempest replaced Twelfth Night and Macbeth was added to the Shakespeare readings; School for Wives was added to the Molière readings. Nor was this a case of initial revisions followed by ossification. As Professor John Rosenberg ’50 observed, of the 150 titles that have been included in the Humanities since 1937, only a few titles have never left the list: The Iliad, the Oresteia, Oedipus the King, Dante’s Inferno and King Lear. Humanities A called on students not simply to read one work each week, but to read all of it whenever possible. “Nearly everyone on the staff … concurs in the opinion that whole books are better than parts,” stated the College’s Committee on Plans in 1946. “And where parts have to be chosen the consensus is: the longer the better.” The rapid pace and the heavy reading load placed special burdens on students, who, after all, were new to college. The instructors recognized that they also would have to help students learn how to read, so learning “mechanics of success” in dealing with coursework became integral to the experience of Humanities A. There are signs that instructors realized that they might be expecting too much; prior to the spring of 1938, instructors advised students to begin both Don Quixote and Tom Jones during Christmas break. In later years, only the first part of Cervantes, or excerpts from both parts, were read. From General Honors and the Colloquium, Humanities A inherited an unswerving devotion to close reading and discussion of important texts, approached from the perspective of an enthusiastic amateur. In structure and staffing, however, Humanities A followed CC. There was a common syllabus, though it was much simpler than the CC syllabus, as it only listed the one book to be read each week. In 1937–38, sections met four times a week, though this was reduced to three times a week in 1941. (Now all Core classes have two-hour sessions twice a week.) There were weekly quizzes and four papers spread across the two semesters. Despite considerable strains on the College’s resources, sections were kept small, averaging only 24 students. In its first year, there were only 20 sections (compared with 56 today). Each section had only one instructor, who remained for the entire year. Like CC, Humanities A relied on staff, drawn from different departments, who met each week to discuss the assigned text.

At the start, those departments contributing instructors for Humanities A overlapped with those teaching CC. Instructors were chosen from the departments of English, philosophy, history, classics and modern languages. While in later years the Humanities staff and the CC staff could often become estranged, initially the College encouraged faculty to teach both courses. And some of Columbia’s most famous professors did teach both, such as the historians Harry Carman, Barzun and Brebner and the philosopher Edman. This community of purpose is hardly surprising, for there was widespread acceptance among the faculty of the goals that both courses shared. On a practical level, both were introductions to the offerings of the College’s many departments. But since these introductions went beyond academic guidance, they were foundational in a much wider sense, providing incoming students with ideas and information that would be valuable for a lifetime. 1. The reasons for the ending of the General Honors course remain unclear. James Gutmann was vague, referring only to a “variety of reasons” and “the defects which had caused the Faculty” to abandon the course. In 1954, Justus Buchler argued that the General Honors sequence was abandoned “because it became incongruous with a systematically evolving organization” of the College. 2. Erskine’s influence on the Humanities sequence was tangential at best. The General Honors course had been abandoned years before Humanities A began, and Erskine only had consulted with the faculty in charge of creating the Colloquium on Important Books. He retired from Columbia to pursue his literary career before Humanities A was first offered. Some of Erskine’s students shaped Humanities A, but not Erskine.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||