|

|

|

|

|

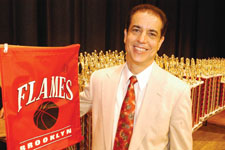

FEATURESFeeding the FlamesGerard Papa ’72 left Wall Street and his law career to run the Flames, a basketball program for inner-city youth in BrooklynBy Robert Lipsyte ’57, ’59J

Gerard Papa ’72 Photo: Chris Taggart  “The only time Christ ever got hostile, expressed any kind of wrath, it was for the religious leaders of his day,” said Gerard Papa ’72, ’74 SIPA, ’75L. “The ’whited sepulchers,’ He called them.” Papa took a breath and laughed a little bark of punctuation he uses to signal irony. “The Catholic Church taught me all this stuff.” “So, you’re Jesus in this story,” I said. We were sitting in his Bensonhurst kitchen, nine years ago, as he prepared to battle the bishops in State Supreme Court. “C’mon, Bob, I’m not comparing myself to Jesus. Any more than the kids on my team compare themselves to Michael Jordan. But you got to strive toward an ideal. I got that at Columbia, too.” “You’re the good man in this story?” “I am not perfect,” said Papa. “No one is. But... yes.” I probably snickered then, but, yes, Papa is the good man in this story. For a quarter-century now, Papa and I have had some version of this conversation. It usually begins – in his house, my house, a gym, a schoolyard, a courtroom, a restaurant, walking the Coney Island boardwalk or riding in his car – with the Flames, a basketball team Papa founded in 1974 that became an inter-racial youth organization that has served more than 15,000 kids. The conversation quickly broadens into discussions of good and evil and then on to Jesus as a role model. Papa, 53, goes to Roman Catholic Mass almost every day. A 68-year-old non-observant atheist, I am the one who tends to lead the conversation from hoops to religion. I am fascinated by his devotion, his constancy, his strength. “So, why do you go to Mass almost every day?” I asked him several months ago. “To pray for friends who don’t pray,” he said pointedly. I was a correspondent for CBS Sunday Morning with Charles Kuralt when I met Papa in 1982. Then, Papa was a subject for my print and television reporting as I followed his epic, violent, nearly fatal, battles against his neighborhood, the city, the Police Department the Catholic Church. More recently, he has become a friend and a hero and a way of thinking about myself and my classmates as we move toward our 50th reunion next spring. Papa is only moving toward his 35th, but somehow it seems as though some of our answers are in his story: What did we really learn at Columbia, and have we done enough since then?

Team photo: courtesy Gerard Papa ’72  Most of my classmates are retired lawyers, doctors, businessmen, travelers, husbands, fathers and grandfathers who talk vaguely about “giving back,” usually in financial terms. Papa never left his mother’s house, walked away from a high-paying job and changed his piece of the world. While there is still time, what can we learn from him? Papa is an unlikely-looking example, I think. In his everyday costume – Flames T-shirt, drawstring white ghetto bloomers and red sneakers – he looks like our wayward son. He doesn’t read books, he tans himself on beaches all summer, he loves to cruise in his 2006 white Cadillac DTS. He sounds like Bensonhurst (a conscious decision, he says), even when he declaims: “There are always good and evil forces in any sea of endeavor. It is up to the leadership as to whether good or evil prevails.” He believes in the great man theory of history, he says, initiated at Brooklyn’s Xaverian H.S., perhaps reinforced by his favorite College professors – historian Robert Kirby and economist C. Lowell Harriss ’40 GSAS – and by his current addiction to The History Channel. “I see the world from the bottom up,” he says, “from the kids in the gym and from the interaction with everyday people. Kids play or fight depending on who is in charge. The same people can do good or bad or be chaotic. It depends on their leaders.” This time, we are sitting on the porch of his house, last August, on a beautiful, hushed Sunday afternoon. His 85-year-old mother, Elena, is inside making me coffee. She is eager to renew our three-decades-old conversation about how much happier she would be if Gerard would get married, have kids and return to a major law firm. When we met, Papa was something of a curio, one of those “local heroes” occasionally discovered by the media and examined anthropologically. “Look at this,” goes the reporters’ message. “Despite no money, no Ivy League connections, no professional training and no political office, these natives have managed to do some good in their villages. How wonderful! A lesson for us all! Can you imagine if they had our advantages? They might be CEOs or senators!” But Papa had our advantages. Raised by his mother, a schoolteacher, he had a rigorous Catholic school education and completed the College in three years, summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa. He commuted, but was freshman class president, advertising manager for Spectator, a lightweight football player and an activist. (In 1968 he was a member of the conservative, anti-anti-Vietnam War group Students for Columbia University.) In his third year at the Law School, Papa ran in the Republican primary for a New York State Assembly seat. He lost big and the campaign soured him on elective politics, but not on public service through the church.

Photo: Chris Taggart  A sports fan who loved basketball, he began to coach an all-white Brooklyn neighborhood team of 14- and 15-year-olds in 1974 at a local priest’s request. He named the team the Flames, after one of his favorite quotes: “Stir into flame the gift of God bestowed on you” (2 Timothy 1:6). The Flames nearly guttered out, failing to win a game in their first season. Papa took it personally. He had to become a better coach. He studied, talked with other coaches, planned his practices and spent time drawing up plays. The following season, the Flames won half their games. By then, Papa was a tax associate at Seward & Kissel – a cocky junior lawyer working for the late senior partner Dick Valentine ’48L, the first of a number of Columbia connections who helped Papa fan the Flames. He also was a young man in what he now calls his “innocent” phase, believing that most people want to do good and that people who do things the right way always will triumph. Papa needed a parish to sponsor him in the Catholic Youth Organization’s prestigious basketball program. Near his home, at the church of Most Precious Blood, he found the Rev. Vincent J. Termine. A crusty, twinkly Brooklynite in his early 50s, a kind of movie priest – “Celibacy was never a problem,” he told me, “and I didn’t take a vow of poverty. But obedience, ah . ” – Father Termine seemed to have been waiting for Papa. He helped Papa paint white lines on the linoleum floor of his bingo hall and erected portable backboards. They held open tryouts. Black kids from the nearby Marlboro projects ventured across the black-white border. When the team was assembled, it was more than half black. Racial integration was never the primary mission, Papa has maintained all these years. Blacks, he told me, “weren’t relevant to where I lived. I had essentially no contact with black people and I didn’t really think about ’em too much.” Papa just wanted a good team. He wanted to win. He says he was surprised when the neighborhood freaked. At the first integrated practice, a van screeched up and a gang of young white men piled out swinging bats. One of them was the son of the local “man of respect.” The Flames piled into Papa’s Thunderbird and raced off to Coney Island, figuring correctly that their attackers would not follow them into a black neighborhood. That season there were telephoned death threats, and Papa’s tires were slashed. His black players were beaten and most white players were pressured to quit. But he refused to disband the team. He believed in his righteousness. He believed that his kind of coach was some kind of priest, not so much a courtside tactician as a saver of souls. Apparently, so did Father Termine: Remembering a piece of advice from his mother – “Better a dead priest than a bad one” – he stormed into the back room of the local social club. Cards and chips flew as Father Termine roared (“I can be dramatic when necessary” ) about Jesus and justice. When he was finished, the team and Papa were promised safe conduct.

Team photo: courtesy Gerard Papa ’72  Emboldened, Papa began swaggering into Brooklyn gyms in a bomber jacket, unshaven, wearing what he called his “ghetto stare, where you look at people and show no emotion.” He was scared for years, but he fooled them. “Most tough guys are actors anyway. You get them alone and they cry just like you,” he says. The Flames became a perennial winner in the CYO, and by the time I profiled Papa for CBS Sunday Morning in 1983, the Flames were a league of their own – some 300 youngsters from 8-19 on 32 “house” teams that played all winter in the bingo hall and on a handful of CYO traveling teams coached by volunteers. Through the years, 13 teams from various age groups wearing the Flames’ emblem – a black hand and a white hand grasping a torch – won Diocesan championships, and Papa coached three of those teams. The style Papa refined on his early teams is the style he imposes today, a projection of his personality. No jump shots allowed, no three-pointers, because you might start to depend on them, take shortcuts and get lazy. Pass only if you don’t have a shot. His kids never stop running, with or without the ball, never stop driving to the basket. When they are cooking, the Flames are quick and brash, like Papa – slapping balls out of hands the way he snaps out demands and retorts, rebounding with their entire bodies the way he has elbowed his way through bureaucratic zone defenses. He found supporters, white and black, in law firms, the district attorney’s office and the media, and enlisted them as coaches, advisers, contributors. He also began to create The Rules. He refined them through the years, but he rarely bent them for expediency. They still exist: No hats, headbands or wristbands in the gym, nothing but uniforms. No girlfriends. In fact, no one is allowed to watch except family members older than 23. And they can clap, but they can’t cheer. Every player needs to do service to the Flames, contribute at least one hour a week to cleaning up, keeping score, refereeing. Older kids coach younger teams. There is mandatory playing time, even if it means talented kids sit on the bench and watch clumsy kids get their minutes. And as a mark of respect to the institution and other kids, you must show up on Trophy Night to get your trophy. Papa’s tryouts became longer and longer as he studied kids to mix and match them on teams, trying to keep a parity of talent, but also to spread race, ethnicity and neighborhood around so kids would make new friends. As the Flames grew, so did Papa. “That first real troublesome year, my problem was coming predominantly from white kids so I started thinking every black kid was good and every white guy was a problem. Over the next couple of years my feelings matured, and I’ve reached the stage where I don’t notice somebody’s color. That’s a fact. Racism’s a two-way street. More importantly, racial fear is a two-way street.” The struggle of the early years also was physical. Papa was exhausted, spending his days on Wall Street preparing complex corporate tax papers, his nights and weekends preparing complex adolescents to play basketball games and deal with a world that often despised them. He was constantly explaining himself to his community and keeping the tough guy pose throughout the rest of Brooklyn, asserting his authority in the gym with rambunctious kids who sometimes needed something more than a bark. He was sustained by his growing role as a mediator between blacks and whites, and by The Lesson: “If you’re doing something that’s good, if you show people that you’re going to stick with it and you’re not going to half-step, you’re not going to hold back, and you’re willing to do it for a long enough period, you’re not going to be somebody who’d throw in the towel and say, 'Well, I tried,’ – then you’re going to succeed.” Doing something that’s good entailed more than running a league and coaching teams. Papa always has been involved in the lives of his players and their families. He hangs out with them. He takes them to dinner (and teaches them how to order, treat servers, eat) and to movies. He gives them endless advice and the kind of attention – the love – so many have never gotten. He writes recommendations; often, he is the only person they know with mainstream respectability. Far too often – he stopped counting at two dozen – he has given the eulogy at their funerals. Papa left Wall Street in 1979. “I said to him,” his mother told me, “you went to Columbia to be in private practice?” And it wasn’t much of a practice, because he was too busy holding basketball practices. Much of the law he did locally was helping kids and their families out of jams. But the money that comes with a Wall Street position wasn’t important to him. “I have everything I need,” he said in 1983, “a great education, the ability to earn however much money I need to earn. When I die, I’ll have money in the bank, so why do I have to worry about having a little more? A poor kid, his duty isn’t to go out and start something like the Flames. It’s his duty to get an education if he can; if not, then some kind of trade, a job, a wife and kids and build himself up. We take things at their own level.” It was in 1983 that Jesus first came up. I asked him about his heroes.

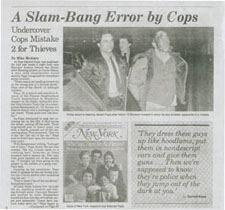

“I see the world from the bottom up.”  “I don’t have any heroes,” he snapped. “I’m a Christian, so that’s a hero right there. But I don’t want to get on that subject. This is not a religious program.” My TV piece was one of a number of stories about him in that time. With his usual directness, he is quick to remind me that his favorite appeared in the Fall 1983 issue of CCT, written by Francis X. Basile Jr. It was a good story, smart and well-written, but it also marked the beginning of the end of Papa’s innocent phase. The loss of his Wall Street salary, the Flames’ main source of revenue, sent Papa into the world of private grants and city funding. There, he antagonized several local power brokers by blowing the whistle on their misuse of funds earmarked for youth programs. There was a Daily News exposť and an indictment. The Flames still didn’t get any money. And, Papa believes, he became a marked man. A few minutes before midnight on March 12, 1986, Papa was driving his powder blue Lincoln Town Car in Coney Island with a friend, James Rampersant Jr., the 23-year-old son of a Baptist deacon. Suddenly, a car came toward them the wrong way. As Papa tried to drive around it, the car cut him off and its doors flew open. Long-haired, roughly dressed men with guns leaped out, yelling. Papa threw his car into reverse and crashed into a second car that had come up to block him from behind. More men with guns jumped out. Papa again tried to drive past the first car, but the Lincoln stalled. The men opened fire. “I thought we were going to die caught in the middle of a drug war,” Papa said afterward. Papa and Rampersant began praying. They heard a police siren, but their troubles were only beginning. The men in civilian clothes – plainclothes cops – dragged them out of the car and beat them. Hours later, Papa was treated for bleeding head wounds and broken ribs, Rampersant for deep bruises. They were arrested and charged with attempted murder, assault, reckless endangerment and criminal mischief. It was three months before all the charges were dropped. A year later, a grand jury report reached “the inescapable conclusion that this was a case of mistaken identity by all involved that led to a chaotic situation, frightening and endangering all the participants, police and civilians, for which no one can be held criminally responsible.” The report also suggested that police be better trained in the dangerous “suspicious vehicle stop.”

A frame from a CBS News 60 Minutes report about Papa that aired in 1989 shows him interacting with his players. Photo: Courtesy CBS News 60 Minutes  Papa saw it differently, as he expressed in the program for the Flames’ 1996 Awards Night: “Ten years ago in 1986, the personal bonds uniting Flames showed their extraordinary strength when Gerard survived an attempt on his life by a gang of crooked Coney Island police. Gerard had challenged powerful politicians for stealing millions in youth funds. The police gunfire and savage beating left him badly injured. To cover up, they jailed Gerard, charged him falsely with attempted murder and tried ruthless schemes to crush him and Flames. In the end, they failed.” They failed because Papa went back to the gym. He seemed a little shaky, diminished, when I followed him around in 1988 with NBC cameras. He had lost some of his zip, his smart-aleck repartee and his quick legal logic. He had headaches and bad dreams. He forgot names. He tired easily. He was still undergoing physical therapy, neurological rehabilitation and treatment for post-traumatic stress. Yet he still seemed more focused and determined than most people. He still had hopes and a plan. “The kind of progress that still has to be made is the kind of progress you have to write onto people’s hearts, not the kind you have to write onto law books. And that’s why things like the Flames are so important. It gives a chance for people to know each other and write things on each others hearts,” he says. And he had a message: “I’ve been a Wall Street lawyer. I’ve known some real rich people. The kind of people you read about. And I’ve worked with the Flames, with some people who are criminals. Also the kind of people you read about. And they’re not much different. If there’s any message I try to preach, it’s that. “It’s easy to hate all black people. It’s harder to hate John Smith, who has a mother and brother and plays basketball with you, unless there’s a reason to hate him. And that’s the core of the program. Whenever there’s a social problem, people think there’s some mystical solution. It’s common sense.” By the mid-’90s, Papa seemed to be recovering from his injuries. Flames enrollment was at an all-time high, as was his credibility among street hoodlums and members of the media, two groups he courted relentlessly. To top it off, he was rich. After a two-week Supreme Court trial in 1990, Papa and Rampersant won $76 million from the city, the largest award in a civil case in Brooklyn. On appeal, it was reduced to $6 million, which they received in 1994. That year, Papa hosted “A Banquet for Angels” at the St. Regis Hotel, an elegant thank-you to 150 people, including the original Flames coaches and the doctors, lawyers, journalists and philanthropists who “got me through.” And then, once again, things got tough. His mother became seriously ill and Father Termine retired. In that vulnerable period, the church he’d always leaned on began to fail him. The new pastor of Most Precious Blood declared “a different vision” for his sports program and the CYO leadership found a way to formally exclude the Flames. The next few years were a scramble to find gyms, leagues, opponents. My notes, mostly from telephone interviews, are filled with play dates in Queens, in leagues filled with synagogue teams. Friends of the Flames slipped them into parish and public school courts to practice. They hustled their way onto schoolyards. They dribbled on. Papa began to reevaluate his religious convictions, especially after the church ignored petitions and protests from white and black parents and from a group of predominantly black ministers from other denominations in the area. “'It’s one thing,” he told me then, “to find out there are bad cops. My kids were always telling me that. But your church?” He barks his ironic signal. “Reading about some guy getting burned at the stake and getting burned yourself are two very different sensations.” Once Papa filed suit in 1997 to force the Brooklyn Diocese to allow the Flames into the CYO playoffs, no one in the clergy would talk publicly about him. But Bishop Joseph M. Sullivan of Catholic Charities, which oversaw CYO, had already set the official line when he told me for a story in The New York Times, “He’s done a lot of good for a lot of poor kids. No one’s denying that. But he’s been a thorn in everyone’s side. He’s not accountable.”

Papa’s beating in 1986 at the hands of plainclothes policemen drew significant media attention. He and a friend, James Rampersant Jr., were awarded $76 million, which was reduced to $6 million on appeal.  The judge eventually refused to make CYO admit the Flames because “a court cannot tell a church what to do in matters that affect the practice of the faith.” He offered himself as mediator, but the diocese turned him down. Then the secular community came through. For the past 10 years, the Flames have been playing at nearby John Dewey H.S., holding their annual holiday tournament there, and growing. Papa has credited his Columbia connections – in particular Saul Cohen ’57, Derek Wittner ’65 (dean of alumni affairs and development), Jim McMenamin (director of principal gifts), Jamie Katz ’72 (former CCT editor), Roger Lehecka ’67 (former dean of students) and Jeffrey Kessler ’75 – for keeping that going, including making calls at key moments to the NYC schools chancellor, Joel Klein ’67. A new season has begun in the Father Termine Neighborhood Basketball Association. About 1,000 kids will turn out for tryouts, perhaps 600 will stay to join teams (“No one gets cut unless you do something stupid,” says Papa) and close to 500 will make it to Trophy Night in May. The Flames still are mostly black, although more middle-class kids are joining, often the sons of former players. Last year, Papa eliminated travel teams. The kids of lesser talent who played on the house teams were getting the most out of the program anyway. And these days, when street agents and amateur coaches with sneaker money are running national teams, tournaments and summer camps for elite players, it is rare for the Flames to attract star talent. It is not, after all, about those kind of hoop dreams. On a summer Sunday with tryouts a month away, we are again sitting on Papa’s porch, reminiscing. I think he has mellowed. He is not so restless. He shrugs. “Over the years, I think less and less about winning and more and more about instilling discipline and ideals, giving kids some structure, a place to go to feel good.” Regrets? “Not getting married and having kids,” he says. “You never could have run the Flames as a one-man band if you had,” I point out. He nods. “And the other is turning down the book and movie offers when they came around in the early ’90s. Talking to the Hollywood guys, I was afraid they were going to change the story, trivialize it. I ended up not giving permission.” “You didn’t sell out,” I say. “See, I always said you were really a priest. Priests take vows of poverty and chastity.”

Top: Papa (left) is joined by Flames board member Saul Cohen ’57 (center) and Father Vincent J. Termine at the Flames’ 2005 Trophy Night. Bottom: Papa (right) and one of his earliest Flames coaches, George Hoskins. Photos: Chris Taggart  He glares at me. “Wanna take a drive?” Still restless. We cruise through Brooklyn in the white Caddy and end up at the storied Bedford-Stuyvesant park, “Soul in the Hole,” a basketball shrine. The games have ended for the day and Papa greets and gossips with a half-dozen meaty, middle-aged black men, including an old supporter, Ray Haskins, a former coach at Long Island University. Papa is more comfortable around these men than with most people, because he has come to think of himself as a black coach, too. They respect that, I guess, because Papa, unlike them, could always have walked away. He had millions in the bank and a white skin and a law degree. Yet, here he is. After a while, we wander to a bench to talk some more. I still don’t have the magic words for my 50th. “So, what’s next?” I ask. “Just keep driving your Caddy until you hit Medicare?” His response indicates he’s given this some thought. “I’m 53, I’ve done some good. It’s natural at this age to question if I’ve done enough, say, compared to someone who runs a corporation or holds political office,” he notes. “And who maybe sold out early to get the job,” I interject. He shrugs. “Hey, it’s the nature of a Columbia guy to question, and I think I could do better. You’ve got to always strive. The purpose of a liberal arts education is to teach you to come to your own conclusions, to stimulate the thought process. I mean, you went there, right?” I snap my notebook shut. “You got enough for your story?” he asks. “I had that years ago,” I reply. “Now I’ve got enough for my reunion.” Robert Lipsyte ’57, ’59J is the author most recently of the young adult novel, Raiders Night.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||