EMMA ASHER

What is the best part about teaching the Core Curriculum?

I can name a couple. The first is, I think that CC is the most important course that students take at the College, and that’s in part because of the actual content of the course. CC historically asks the important questions that we in a modern liberal democracy have to confront: What is justice? What do we owe each other and how ought I to live? What are my ethical obligations to myself and to others? How did we get the world that we live in? When you take it all together — the readings and the assignments and all the work — it provides a powerful explanation of the important moral and political ideas that shape our current world order.

The second is the students. These are students who are making important decisions about their majors. Whether they like it or not, what they’re going to study will shape their future. CC students are at a critical juncture in their lives. And so it’s a crucial time to be asking these huge questions about, for instance, how did we get here? As a professor, I see my students encountering this all the time. And as a scholar of Plato, it’s interesting that oftentimes, a character in the Platonic dialog is somebody who is roughly the age of our sophomores, trying to figure out what they’re going to do.

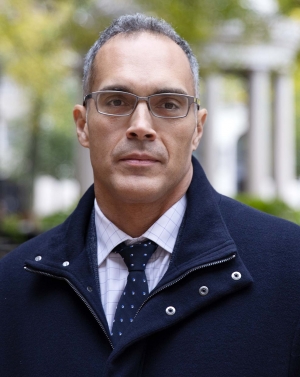

And finally, the last is my own self. I am Latino; I might be the first Latino chair of CC. And one of the conditions that I find — as the child of immigrants, one of whom was a refugee — is that CC is an education for me, too. I’m constantly revisiting and relearning the world order that I find myself in by virtue of teaching this material to the students and to the faculty who teach in the Core.

How do you innovate and/or bring your own spin to CC?

On the one hand, I’m coming at this as a classicist; part of what I bring is a historical perspective on this material that comes from that expertise. But I think the other thing I bring is a sense that the ancient world is a very foreign country: the past is a very foreign country. Ancient Greece and Rome were highly sophisticated, developed societies with their own histories and cultures, which, if you step into that world, looks radically alien to our own. So I think one of the things I bring is this idea that when you enter a course like CC, part of the goal is to see the world from a fundamentally different perspective than your own. I see my job as a CC teacher as one that makes alien arguments seem reasonable, and to make comfortable and familiar arguments seem strange and foreign.

And then another thing that I do is have my students write by hand — no laptops or screens. It’s very old school, but it feels increasingly innovative; it often leads students to think and read in ways they haven’t thought. There’s a lot to be gained from closing a screen and actually thinking about an argument or a text.

What are you teaching that feels especially relevant for this year?

The last four or five sessions of the syllabus are designed to address contemporary problems; so we’re dealing with climate change as a philosophical problem, we’re dealing with contemporary issues of race and gender as philosophical problems, we’re dealing with postcolonialism as a contemporary philosophical problem. So a lot of really hot-button issues are on the future agenda.

But right now, we’re having sessions on Machiavelli’s The Prince — along with Machiavelli’s The Discourses. The Prince is an argument or an explanation of how, essentially, tyrants ought to behave in order to acquire power. We call some princes, but they’re essentially tyrannical. And then The Discourses is a series of arguments in favor of Republican representation as an ideal form of government. Teaching these two texts, which were written right after Florentine Republicanism was destroyed by a monarch — or by simply a tyrant — seems incredibly current.

What has been your favorite Core Curriculum teaching moment?

I’ve had many wonderful experiences, but I’ll say two. CC is a very labor-intensive course for the students and it’s more so for the faculty. When you go into teaching CC, you think that it’s going to, you know, drain you. But one of my favorite aspects of teaching is that I come out of that course more energized than I went in; I almost always get more energy from the students and from their engagement with the material. I leave with more adrenaline and am sometimes even unable to sleep, rethinking the arguments the students made.

And then another was when we came back from the pandemic, and the stakes of being in a classroom were so high; the idea that you could be present and talking about these texts at that time was really extraordinary. I had students come to my office hours! I actually had to buy new furniture for them to sit down on. There was kind of like a post-pandemic reconstitution of what Columbia can be that was exhilarating.