|

|

|

|

|

COVER STORY

His "History of the City of New York" is one of the most popular courses on campus, typically attracting 300-plus juniors and seniors to 309 Havemeyer. His all-night bike rides through Manhattan are legendary. The Encyclopedia of New York City is a must-have for anyone remotely interested in the city. In his three decades at Columbia, Kenneth T. Jackson, the Jacques Barzun Professor of History and the Social Sciences, has become both a world-renowned urban history scholar and one of the most popular professors among students. "You can't throw a rock on the Upper West Side without hitting someone who took that class," says Ric Burns '78, who never had Jackson as a teacher but grew close to him during the filming of his landmark PBS project, New York: A Documentary Film, on which Jackson served as a senior academic adviser. Students, faculty and alumni alike talk about how kind and open Jackson is. Invariably they use the words "energy" and "enthusiasm" when describing him and his teaching style. Many attribute his charm and good nature to his southern roots - Jackson grew up in Memphis, Tenn., and retains the kind of drawl not often heard in New York, as well as a penchant for Pepsi. He's the type of teacher who, in addition to the many outings that are part of his courses, holds barbecues for his students and invites them into his home. "He's warm and he's accessible," says Rosalind Rosenberg, professor of history at Barnard and a friend of Jackson's who credits him with making her feel especially welcome and comfortable in her first few years at the University. "At a big university, the people who can connect quickly are valuable resources. He's always thinking up these folksy things to do. The southern tradition of hospitality means a lot to him." It also means a lot to the students who benefit from this kind of personal, yet educational, engagement.

"There's a glass wall that sometimes gets put up between professors and students," says Suzy Shuster '94, who had Jackson as an academic adviser and became close to him when she took his seminar on New York City. She fondly refers to him by his nickname, K.J. "He lets you in. You can ask him questions without feeling foolish. K.J. lectures you like you're friends sitting in the living room in front of a fire. He might even throw in a couple of expletives or jokes for effect. He always knows how to find stories to get his point across." Like his story of Typhoid Mary and her role in the early 20th-century outbreak of typhoid fever in the city, which keeps his lecture class enthralled. Or his mesmerizing tale about the prison ships anchored in New York's harbor during the American Revolution, on which British forces kept captured rebels - a story filled with vivid descriptions of nasty, disease-ridden conditions below deck. This tale includes a titillating theory about how an illicit love affair between General Sir William Howe, commander of the British forces in the area, and the wife of the man in charge of providing rations to the prisoners may have prompted the cuckolded husband to serve the appalling mess that masqueraded as food to the famished prisoners. Shuster, a reporter for Fox Sports Net in Los Angeles, says Jackson's lessons have resonated throughout her life. "I think about him all the time when I'm doing my sports stories. I always find myself looking back and trying to make historical connections and find characters to tell my story. That's something I learned from K.J." Clearly, Jackson has had a major impact on Columbia, its students and the city. Kathryn Wittner, junior class dean at the College, says it has been interesting to watch the intersection of Jackson's work, the revival of the city and the rising popularity of Columbia. "It's kind of like the stars are aligning," she says. "When I first came to Columbia in 1989, the school was really downplaying its presence in the city. Columbia kind of apologized for its location: 'We've got this great school here, but, well, we kind of happen to be in New York.' People like Ken Jackson and his work have really helped change opinions about the city and the school." Jackson neither acts nor speaks like a typical professor. He doesn't have perfect elocution and diction, but he sure knows how to get a point across. Listening to him is like going on a Sunday drive in the country. Naturally curious, he'll take you down one fork in the road and then backtrack to explore another equally entertaining and evocative path. He easily moves from talking about last fall's Subway Series in the fervent tone of a true baseball fan (a Yankees fan, by the way) to the historical significance of subways and public transportation and the wonderful urban moments afforded by a tradition-steeped stadium in the bustling Bronx. No new baseball palace on the West Side of Manhattan for him, thank you very much. Jackson shrugs off a question about the reasons for his enormous popularity among students. He knows his affection for the city is contagious, but he also wonders if his easy-going style might be another reason students find him so approachable. "I've never thought of myself as an intellectual," he adds, offering up another possible explanation. "That's bull," says Shuster. "He hides behind that whole, 'I'm from Memphis' thing. He'll say 'I'm not an intellectual,' with his southern drawl, but he'll look at you with that sly, wry look out of the corner of his eyes, and we know he is one. Otherwise, why would so many people listen to what he has to say?" She's right. Don't let Jackson's aw-shucks attitude and casual style fool you. There's no doubt that he is a serious historian whose contributions to urban history, and specifically to the study of New York City's history, have been unrivaled. From Memphis to Manhattan

The question most often asked about Jackson is why him and why New York? How did this nice guy from Memphis come to love New York so much and turn into its biggest advocate? "It is truly hilarious that the premier historian of New York City is a southern boy," says Rosenberg. "In New York there's a premium placed on sophistication and a certain iciness and remove. Ken's not like that. He's a real direct, no-pretense person. He doesn't stand on ceremony." So why him and why New York? In his large, book-lined office situated in the corner of the sixth floor of Fayerweather, Jackson tries to answer that question. Leaning back into his chair and stretching out his legs, he seems at this moment to embody the phrase so many people use to describe him: laid-back. Jackson attributes much of his success to being in the right place at the right time or to being lucky, and often downplays his accomplishments. It's part of his modesty; he wouldn't be the type to boast, for instance, about publishing his dissertation at age 26, about earning tenure at 31, or about writing one of the definitive books on the growth of American suburbs. When Jackson spins the tale of his life, you often hear words like "luck," "random," and "just because." Rest assured, there's usually more to the story. Born in 1939 in Memphis, to a father who was an accountant and Army officer and a homemaker mother, Jackson is the second oldest of four children, the only boy. He grew up primarily in a Levittown-style tract house that, while within the city limits of Memphis, had a suburban feel to it. It was the kind of place he'd later research and write about in books like Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (1985), which would win both the Francis Parkman and the Bancroft Prizes as the outstanding work in American history. One of Jackson's earliest lessons in the importance of urban centers came from his mother, Elizabeth Willins Jackson. A supporter of downtown commerce and a believer in Main Street, she often would go out of her way to avoid shopping in the suburbs. Jackson's youngest sister, Margaret Vaughn, remembers her brother as a good student who earned high marks even though he wasn't particularly studious. She also recalls how as a young boy he served as a leader - perhaps ringleader is the more fitting term - of a group of neighborhood kids and family who called themselves the "Jolly Six" and roamed the streets and lawns of Memphis. "He was always in charge," recalls Vaughn. "And we were a bossy family, so that was no small feat." After high school graduation, Jackson took a job in a downtown department store as assistant manager of the shoe department. Impressed by Jackson's sales skills, the store manager tried mightily to convince him to pursue a career in retail. Fortunately for urban history and Columbia, Jackson decided to enroll at Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis) and major in history. That's where he met his wife Barbara. The story goes that Jackson's mother spotted Barbara walking across the campus and said to her son, "There's a pretty girl. Why don't you go talk to her?" The obedient son listened to his mother, and it turned out the young woman was much more than just a pretty face. "She's very smart - one of two people who graduated with a higher average than me," says Jackson, "which she won't let me forget anytime soon." Barbara Jackson chairs the English department at Blind Brook High School in Port Chester, N.Y.

A Woodrow Wilson fellowship gave Jackson the opportunity to leave Memphis. He set off for graduate studies at the University of Chicago, where Professor Richard C. Wade would become an early mentor. In fact, it was Wade who coined the term "crabgrass frontier" that Jackson later used in his work on the suburbs. "So often what happens to you in life is you get under the influence of a person or a group of people and it takes you in a new direction," says Jackson. "I took [Wade's] course at random, for lack of anything better to do, and it's the kind of thing that changed my life because he was excited about cities. As Wade pointed out to us, historians had really ignored the cities. There was still this frontier myth in the United States - open land and cowboys and Indians and all that - so at that time in the mid-1960s, urban history was a very new field. It had promise and excitement." That promise and excitement would have to wait a bit. The Vietnam War was heating up and Jackson had an ROTC obligation from his Memphis State days that had been delayed while at Chicago. In 1965, he was sent to the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, where he served as an assistant professor of logistics management, teaching management techniques to maintenance and supply officers. By the time he had finished his three-year stint, Jackson had completed and published his dissertation, The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930, and begun to look for a full-time faculty position. When Columbia offered him an assistant professorship in 1968, he felt that while he probably would not get tenure at the school, the experience would be invaluable. "I figured it would be a nice stepping stone to wherever I wound up, the University of Nebraska or whatever," he says. "I thought it'd be a nice place to be from. I always imagined I'd end up teaching at a small liberal arts college like Wabash College in Indiana or something like that." So he packed up Barbara and their two young sons, Kevan and Gordon, for the move to the big city. But Jackson would stay at Columbia. And he would get tenure approved in 1970 at age 31. Jackson helped organize the school's first urban studies program - an inter-disciplinary course of study - and later contributed to the program's restructuring. Over the years he has taught the history of the south, social history and military history. But it has been his courses on New York City, particularly the lecture course, for which he's most widely known. City as Classroom

Jackson's affection for New York is contagious. He loves the city, not because it's perfect, but because it's imperfect and always evolving. Early on, he latched onto the idea of using New York City as a prism through which to look at American urban history. Since the city was just outside the Columbia gates, it was only natural that its streets would become a second classroom for Jackson and his students. The class evolved into a smorgasbord of activities, some required, some optional: walking tours, community service projects, guest lecturers, and most famously, an all-night bike tour of Manhattan. In 1972 Jackson rented a bus and hit the road with students to get a close-up look at Brooklyn, the Bronx and suburban Westchester and New Jersey. Manhattan seemed inaccessible because of the traffic and congestion, but one day it struck him that those factors were less of a hindrance at night, and that bicycles would afford a chance for a more intimate look at the borough. Thus was born the all-night bike ride. People who have gone on the ride usually say it's one of their favorite Columbia memories. And why not? Picture a group of 300 students, teaching assistants, guests, administrators and assorted hangers-on, riding at a leisurely pace through the streets of Manhattan behind Jackson and his megaphone. Jackson's sister, who tagged along last year, likened the experience of seeing her brother at the front of the mass of people to her childhood memory of seeing Elvis Presley at a movie theater in Memphis with the crowd sitting behind him in awe. The group makes its way from Morningside Heights through Central Park and Times Square, down past the bustling and pungent Fulton Fish Market at 4 a.m., ultimately crossing the Brooklyn Bridge to get a sunrise view of the city that never sleeps. Jonathan Lemire '01, a history major from Lowell, Mass., said a big reason he came to Columbia was his interest in the city. He jumped at the chance to take Jackson's class as a junior and to go on the bike ride. "I remember we were at the Bethesda Fountain [in Central Park] and were headed south out of the park and down Seventh Avenue. You could see all the lights of Times Square," Lemire says. "This adrenaline rush just went through the crowd, we were all yelling and so excited. Then we literally rode through Times Square - to the amazement of pedestrians and cab drivers, we rode right through Times Square!" The bike ride has grown to such proportions that planning it resembles an exercise in military strategy and precision, giving Jackson an opportunity to utilize his Air Force logistics training. A CAVA medical van and a repair truck accompany the group. Jackson enlists helpers to block traffic as the riders pass through busy intersections. He also plots out restroom and food breaks along the way. He's usually hoarse for several days after the ride.

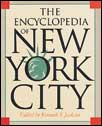

Jackson claims at least one marriage and countless relationships have come out of the all-night bike ride. It's certainly not hard to believe; people who have participated report a feeling of magic and camaraderie that develops over the course of the evening. It's just one way Jackson has for making his students feel special, something he manages to do in the classroom as well. "He makes you feel like your thoughts and opinions and your take on history are important," says Shuster. "When you're 20 years old, that's invaluable." Students have bestowed all kinds of accolades on Jackson. He received the Mark Van Doren Award for excellence in teaching in 1989. In 1993 Playboy named him one of the most popular professors in the nation. He's frequently asked to speak at class reunion dinners and alumni programs. Jackson is known as being incredibly supportive, say students who have worked closely with him - especially if you manage to get him without any interruptions, that is. His phone rings every few minutes with requests from students, reporters, filmmakers and colleagues. He's always willing to lend a hand, give some advice, or just shoot the breeze. Many students keep in touch with Jackson for years after leaving Columbia. Janet Frankston '95, who took both Jackson's lecture and seminar on the city and also contributed articles to the Encyclopedia, remembers how after enrolling at the Journalism School and learning that she would be covering Washington Heights, she asked Jackson what he knew of the neighborhood. "He told me he didn't know much, but that I certainly would [after reporting on it] and I could lead his walking tour." Sure enough, eventually Frankston did lead Jackson's students on a walking tour of Washington Heights. Jackson lavishes as much praise on his students as they do on him. "They have a kind of inquisitiveness," he says. "They're intellectually curious and they're not afraid to express their opinions. Part of that comes from being New Yorkers. I think Columbia students are comfortable with exercising their own prerogatives." The Encyclopedia of New York City

Besides his courses, field trips and excursions, Jackson has spent much of his time at Columbia working on the mammoth Encyclopedia of New York City. In 1982, Edward Tripp, an editor at Yale University Press, approached Jackson about taking on the project. "Fortunately, I was already a full professor with tenure by then. I was intrigued by the idea of doing it, but it's not exactly the kind of project that would get you tenure," Jackson says. Perhaps not, but a medal of some sort seems deserved for the 13-year battle it took Jackson and a half dozen full-time staffers to complete the work. As the book neared publication, Jackson says he'd often wake up with nightmares of omission. "I was worried we'd forget something major, like Harlem. Can you imagine?" he says. Jackson's fears were largely unfounded, though he does wish he'd remembered to include an entry on the Municipal Arts Society, a venerable New York institution that "just sort of fell through a whole bunch of cracks," he says. "That's really the only one we just missed." Jackson points to a foot-high stack of folders and papers in a corner of his office, notes, suggestions and reminders for a possible second edition that may be published in the next few years. "It would be 30 or 40 percent new material," he says of the update, to which he would like to affix a new index. Jackson swears he read all 1.4 million words in the 1,373-page book - "some more than once," he adds. "I felt it was my responsibility to edit every single entry." Fred Kameny, executive editor on the project, vouches for that. He calls Jackson a great editor who deftly handled questions about how particular entries should be slanted, and who knew when and when not to go to the mat in disagreements with contributors. "He has the most important attribute an editor needs: judgment," Kameny says. "And his judgment is unerring." Bringing History to the Masses

Turn on A&E, PBS, or the History Channel at any given time and you might well see Jackson expounding on something - New York, suburbs, military history, the automobile, a Western movie, you name it. "I believe that the role of the scholar is to be part of the larger world," he says, "to make history exciting and relevant, in whatever form it takes." He is a commentator on the History Channel's Movies in Time series and a jury member for its Herodotus Awards, or "Harry's," the network's version of the Oscars, awarded to films that accurately portray history. " A lot of historians might look down on this kind of stuff, but [Jackson] knows there's more to history than academic writing and college teaching," says Seth Kamil, a graduate student who founded Big Onion Walking Tours of the city after taking Jackson's course. "He understands as a fundamental truth that history is stories, and sometimes stories of history are disparaged by scholars as not being sufficiently abstract," says Rosalind Rosenberg. "But he's able to tap into those stories and make great historical points." While Jackson may be known for his populist approach, he's also a serious scholar. Just as he was able to sell shoes back in Memphis, he knows how to sell a story. "Ken is always trying to point academics to a wider audience, not by sacrificing standards, but by writing clearly and with a breadth of imagination," says Evan Cornog, associate dean of the Journalism School and a former graduate student of Jackson's. The lasting impact that Crabgrass Frontier has had in the field of urban history since it was published in 1985 is testament to his success at that. Shortly before Jackson completed Crabgrass, his 16-year-old son Gordon died in a car crash a few miles from the family's Chappaqua, N.Y., home. (The Jacksons also have an apartment on the Upper West Side.) He writes movingly about the loss in the acknowledgement pages at the beginning of the book. Students are often surprised to come across the note when reading the book for class. "Consistently throughout the semester, [Jackson] talked about public transportation and his support for it," says Stephanie Hsu '01, who took Jackson's course a year ago. "At one point he mentioned that he had lost someone dear to him in an automobile accident. Then I read the introduction to Crabgrass and saw that it was his son who had died, which was pretty shocking. I really respect the way he's taken that terrible tragedy and built this very well-supported, scholarly argument and advocacy for public transportation." After his son's death, Jackson moved to Los Angeles to teach as a visiting professor at UCLA. "Partly it was an escape," he says. "We didn't know what we'd do. We'd had a couple of offers from other universities and some people told us that's what you should do after a tragedy like that, just kind of start your life over again." Although he liked Los Angeles, Jackson and his wife decided to return to New York and Columbia. Rumors abound that Jackson is such a workaholic that he keeps a sleeping bag stashed in his office. Kamil remembers how he once called Jackson's office in the middle of the night intending to leave a message on his voice mail - so as to avoid being asked the dreaded "How's the dissertation going?" question - only to be surprised by the sound of an alert Jackson on the other end of the line. Jackson admits to occasionally working through the night and sacking out for a few hours on the black leather couch in his office ("I'm getting too old for that; it's not so good for your neck," he says), but he brushes aside the theory that he's a workaholic. "I'm only a workaholic if you suggest that I spend vast amounts of time reading - which I do, but I'm interested in it, so it's play. My wife thinks of it as playing, but really I need to do it for my work as well," he says.

Jackson, who is teaching only a graduate colloquium this spring, is co-chair of the planning committee for the University's 250th anniversary celebration in 2004. He's also president of the Organization of American Historians, and will deliver his presidential address in Los Angeles in late April. Yet Barbara Jackson senses that her husband is eager to get back into the classroom. "Teaching is his passion. He's a born teacher," she says, noting how they often share ideas about how to be more effective in the classroom. It's not all work. When he's not preparing for class, leading walking tours, advising students or working on one of his projects or committees, he manages to unwind, often by playing games of pickup basketball. "On the basketball floor, people don't even know your name," he says. "You're judged only by what you can do with the ball. It can be a very humiliating and humbling experience because if you can't run fast, or jump high, if you can't bounce the ball behind your back, you're not going to get chosen. And if you look old..." he says, his voice trailing off. Apparently, the 61-year-old Jackson is still getting picked for games. He attributes a recent 20-pound weight loss to his increased sessions on the court. Jackson frequently commutes to campus with Derek Wittner '65, executive director of alumni affairs and development for the College, and his wife Kathryn. "In the best sense, Ken is a child in adult clothing (when he remembers to pick up his pants at the cleaners)," says Wittner. "He has endless energy, enthusiasm and an insatiable inquisitiveness. His jump shot may not be what it was, but his breadth of interests and information make him a wonderful commuting companion for Kath and me." Kathryn Yatrakis, associate dean of the College and dean of academic affairs, remembers playing basketball against Jackson years ago. "He's pretty good," she says, "but while he might be waiting by the phone, I really don't think the NBA is going to be calling anytime soon. Unless, of course, they're looking for someone to write the history of the league!" About the Author: Traci Mosser '95 has one regret about her Columbia years: missing the all-night bike ride. She hopes she might be able to wrangle an invitation for next year's trip.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

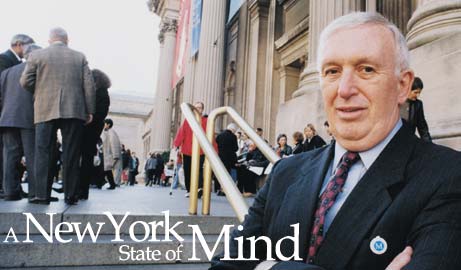

Popular professor Ken Jackson has shared his passion for history

and the city with Columbia students for more than 30

years.

Popular professor Ken Jackson has shared his passion for history

and the city with Columbia students for more than 30

years.