If you know of a Columbia College student, faculty member, alumnus/alumna or program we should spotlight, or if you would like to submit a story, please contact:

Columbia College

Office of Communications

cc-comms@columbia.edu

“We believe that through discussion, mentorship and knowledge, we can empower young Native people, ourselves included, to be agents of change in Native communities.” — Fantasia Painter CC’13

In the summer of 2013, Fantasia Painter CC’13 spent two weeks volunteering in New Mexico with AlterNATIVE Education, a program she co-founded as a student. This year, AlterNATIVE, a week-long peer-education and mentorship program run by Columbia students and alumni that encourages Native high school students to consider higher education, returned to New Mexico to work with five Native communities. Here, Fantasia shares her reflections on AlterNATIVE’ s second summer.

Albuquerque, NM --- It is a Sunday morning in July. The red rental van is packed full of volunteers who arrived the night before. I follow behind in my grandmother’s ’91 Toyota Tacoma, suitcases crowding the bed of the truck. We arrive at Tiguex Park in Old Town Albuquerque.

At the park we unload the volunteers and our picnic-style lunch. This is the volunteer orientation for AlterNATIVE Education, a week-long peer-education and mentorship program run by Columbia students and alumni that encourages Native high school students to consider higher education — though this year, our second year, we will also have a few younger students as well. And so my opening question is: "Why AlterNATIVE Education?" The volunteers consider this question before they begin writing. "Why did you choose to volunteer?" I follow up.

We go around and share, and although our individual answers are different, a common theme quickly emerges: We wish there had been a program like this when we were in high school. We are here because, as indigenous college students and graduates, we believe that Native students, communities and leaders benefit from engaging in discussions about Native histories and present issues — conversations that are not happening in American high school classrooms. We believe that we can encourage Native students to go to college. Ultimately, we believe that through discussion, mentorship and knowledge, we can empower young Native people, ourselves included, to be agents of change in Native communities. And so we are here, to spend one week in each of five communities over a three-week period, engaging, encouraging and empowering Native students through AlterNATIVE’s program.

Megan Baker CC’14 leads class discussion at To'hajiilee. Photo: Fantasia Painter CC’13

Megan Baker CC’14 leads class discussion at To'hajiilee. Photo: Fantasia Painter CC’13

AlterNATIVE began as a postscript project to Daniel Press CC’64’s spring 2013 class, Approaches to Contemporary Native American Education, part of the growing Indigenous Studies track of Columbia’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race. It was here, after learning about Native education in our own communities and communities across the nation, that I, along with several of my classmates, decided that a 50 percent high school graduation rate among Native Americans (compared to the national average of 86 percent) should be everyone's concern, but especially ours. We were members of the small percentage of Natives that attend college out of the 50 percent that graduate high school, out of the 2 percent of Native Americans in the United States. If anyone knew something about how to get Natives into college and the obstacles they would face before, during and beyond, it was us. We decided that we had to do something.

And so we did. In the summer of 2013, Marial Quezada CC’14 and Christian White CC’15, along with the help of David Schwartz, a senior program associate at Facing History and Ourselves, a nonprofit specializing in the pedagogy of genocide, compiled our in-class recommendations, discussions and ideas, and developed a week-long curriculum. AlterNATIVE Education was born.

From there, we took to the streets. The program was piloted during the summer of 2013 over the span of two weeks in Zuni Pueblo, Pine Hill Navajo Community, Isleta Pueblo, and To’hajiilee Navajo Community in New Mexico, with the support of Columbia’s Alternative Break Program and the Indiegogo-raised support of our family, friends and communities.

It was everything we had hoped for. Students were eager and engaged in conversations about the more than 500 years of Native American genocide — a genocide that was largely instigated by a desire for the possession of land and resources, but that also includes the cultural genocide of Native languages, religions and histories within all of American society and education. Discussions about these various stages and definitions of Native American genocide were coupled with an examination of the simultaneous 500 years of Native resistance and, most importantly, about the possibilities for and our agency in shaping Native futures.

Fantasia Painter CC’13 (center, bottom row), Christian White CC'15 (center, back row) and Tristin Moone CC'15 (center, holding flag) in To'hajiilee with students during the summer of 2013. Photo: John Gamber, AlterNATIVE academic adviser

Fantasia Painter CC’13 (center, bottom row), Christian White CC'15 (center, back row) and Tristin Moone CC'15 (center, holding flag) in To'hajiilee with students during the summer of 2013. Photo: John Gamber, AlterNATIVE academic adviser

Now, a year later, I am back in New Mexico. AlterNATIVE is now officially a nonprofit and I, along with 11 other Columbia students and graduates, am here to facilitate AlterNATIVE’s second summer of programming. During the second of this summer’s three week-long sessions, I am the team leader in Tohajiilee, a small Navajo community about an hour outside of Albuquerque; our group includes Megan Baker CC’14, Christian White CC’15, Sarah Stern CC’16 and Braudie Blais-Billie CC’16. A second contingent — Marial Quezada CC’14, Danielle Lucero CC’15, Sara Chase CC’14, Noah Ramage CC’17, Kyle Sebastian CC’16 and Michelle Crowfeather CC’17 — spend the same week in Isleta Pueblo.

Even the second time around, the first day in the classroom is rough. Convincing early high school students to talk about themselves is surprisingly difficult, and convincing them that we're “cool” and here to talk with them, not at them, is even more challenging. Then, on the second day of the session, we get to stereotypes.

Braudie asks the students to brainstorm stereotypes about Native people and peoples, individuals and communities. The room explodes. "Johnny Depp!" "Pocahontas." “Casinos.” “Brown.” “Tipis.” "Long black hair.” “Closer to the earth.” The list is extensive. When AlterNATIVE is covered by NBC, in late August, it chooses a photo from this day — one of my favorites: Braudie in the foreground and the board inundated with misconceptions about Native people and peoples behind her.

For many of the students we are with, this is the first time they have openly talked about stereotypes, let alone stereotypes that directly affect them. Though Native American communities define this continent and nation, there is an overwhelming silence in classrooms across the country when it comes to contemporary Native representation and realities.

While the average American is ostensibly unaffected by, and in some ways actually benefits from, this silence, the lack of dialogue about Native communities is visibly detrimental to Native American individuals and communities alike. Native people and Native communities have been systematically stripped of their lives, languages, economies, religions and cultures during the last 500 years.

Today, Native communities still feel the effect of that legacy of genocide. On a macro level, Native communities face social, economic and physical challenges. On an individual level, Native people are asked to identify with caricaturized representations and then expected not to take offense at a vast array of microaggressions that abound in our lives — for example, we are told to stay calm when, because a true representation of Native communities is lacking, non-Native people ask us what our Indian name is or if we live in tipis.

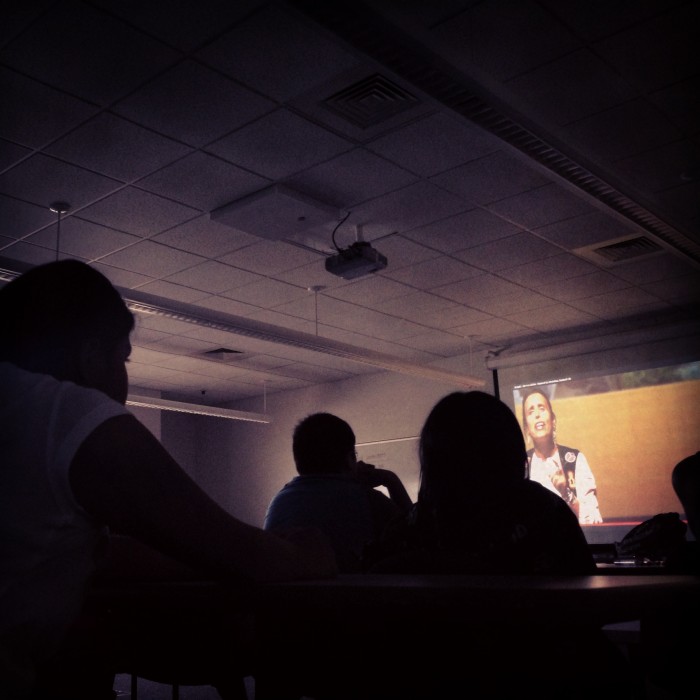

Students engage with a Winona LaDuke video on food sovereignty at Zuni Pueblo. Photo: Fantasia Painter CC’13

Students engage with a Winona LaDuke video on food sovereignty at Zuni Pueblo. Photo: Fantasia Painter CC’13

This isolation and lack of understanding about where we come from and where we are now only serves to make individuals in our community feel more helpless and alone. We are taught that Native Americans are either cartoons riddled with stereotypes or are inauthentic in their deviance from the “real” Indians who lived 300 years ago. There is no positive and realistic representation in American society with which we as individuals and as communities can identify.

This is where AlterNATIVE fits in. Our goal is to create a space where students can talk about the legacy of genocide and colonization, how those legacies affect Native pasts and presents and, more importantly, what Native futures do and could look like.

Throughout the week, we discuss Native American identity, histories, stereotypes, tribal governments, narratives, arts and current events. We go through these topics to ask ourselves how we, as individuals, effect and affect our Native communities, and vice versa to discover how our Native communities’ pasts and presents have shaped us.

Press, our organization’s mentor and a lecturer in Ethnic Studies at Columbia, often recalls when, during our first summer in Pine Hill, Navajo, one young woman, with arms outstretched, said that justice will be when the whole world knows about what happened to Native Americans. This is one of my favorite stories, because for me it epitomizes AlterNATIVE’s success. All of this culminates in investigating how college can be used as a tool of resistance, self-determination, and sovereignty. It is also in this final part of the program that we develop one-on-one mentorship relationships that we hope will encourage students to consider higher education as a tool of resistance.

We hope to realize this student’s vision, one our organization shares. This summer we returned to the four communities we worked with last year, and added a fifth, Farmington. We have reached more than 100 Native students thus far, but we imagine a day when every university is partnered with a reservation high school, a day when the country is educated about Native American genocide and when Native people and peoples flourish.

This is my last year in the classroom through AlterNATIVE — I graduated from the College in 2013 and next summer will be too old to connect with high school students in the same way. But the lessons I have learned through AlterNATIVE will stick with me, as will Tedra and Alexis, my mentees. I will always have them, and they will always have me.

Fantasia Painter CC’13is a co-founder and acting director of development at AlterNATIVE Education. She is a Questbridge scholar from Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. This story appeared in the 2013–2014 Columbia College Annual Report.

There are myriad people to thank here for, like all things, it was a community effort: The Native communities that we continue to collaborate with; our mentor and program advisor, Daniel Press CC’64; our faculty adviser, John Gamber; Alternative Break Program Director Peter Cerneka; Frances Negron-Muntaneer in The Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race; David Schwartz and the whole of Facing History and Ourselves in New York; the friends, family and communities who donated via Indiegogo; and the facilitators and all those who care to ask questions about contemporary Natives.