Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Women’s Wisdom

Natasha Cunningham

Ellis, a journalist and filmmaker who is the digital anchor for PBS NewsHour, found her focus for We Go High: How 30 Women of Color Achieved Greatness Against All Odds (DK, $19.99) when she considered the ways she had navigated challenges in her life and career. “I thought of the roadblocks I’ve hit and how I’ve self-soothed and persevered through them, and a lot of it came back to reading about other women of color,” she says. “So I thought about this book through the lens of, ‘How can I add value in the ways that so many of these women and authors have added value to my life?’”

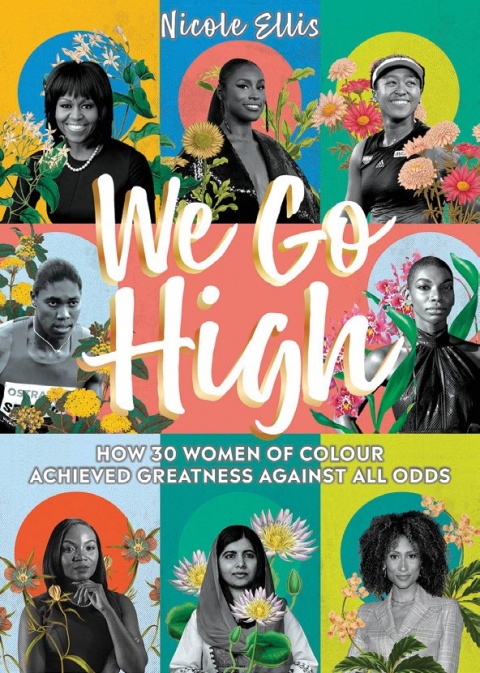

Ellis considers We Go High as “self-help by proxy”; the collection includes encouraging life stories, motivational quotations and personal philosophies from role models such as Vice President Kamala Harris, actress Issa Rae, Olympic gymnast Simone Biles and, of course, former First Lady Michelle Obama, whose wisdom inspired the book’s title. The profiles are accompanied by striking photo illustrations by Natasha Cunningham, who communicates a sense of growth by embellishing each portrait with flowers and natural elements.

By detailing how these women overcame obstacles, Ellis hopes to remind readers that they are not alone in the hills and valleys of their own lives. The book took more than a year to research and write, done in her free time from NewsHour. She wanted to represent a range of industries, skills, aspirations and lived experiences; while the emphasis for some pieces was clear because of the person’s celebrity, Ellis needed to dig deeper with others to glean “that nugget of identification” for readers to connect with. “That reporting was the most fun part because I got to read so much,” she says.

Ellis got hooked on storytelling at the College, and credits one seminal class — Pegi Vail’s “Film and Culture” — with setting her on her path. “I thought it would be easy: just watching documentaries one night a week,” Ellis says. “I ended up falling in love with the visuals and the exposure to different cultures.” She became an anthropology major, and after graduation took two years to backpack solo around the world. While publishing a travel blog about her adventures, it occurred to her that a storyteller can shed light on lived experiences for others. That awareness eventually led her to enroll in the Journalism School.

Ellis joined The Washington Post in 2017, hosting, producing and directing original and breaking news videos that aired on the Post’s website. She was nominated for an Emmy for her coverage of Hurricane Harvey in 2018. Three years later, Ellis joined NewsHour as its first-ever lead anchor for digital video, which includes hosting pre- and post-shows and livestreams.

“My passion is being a chaperone for people so that they feel safe enough to learn something new,” Ellis says. “It’s why I became a journalist in the first place. Whether it’s the nightly news, or learning about their bodies, about science, about gender, about identity, you name it — learning how people navigate a hurricane! I want to facilitate the kind of spaces that make my subjects feel comfortable.”

Sharing the ways in which people weather hurricanes of all kinds is the work of We Go High. The profile of politician, lawyer and activist Stacey Abrams, excerpted here, is one Ellis felt especially connected to. Abrams believes that while it’s important to grieve after you get knocked down, you should either harness the experience and those emotions to strategize how you intend to achieve your goal, or move on to something else.

“That one sticks out the most for me, because it’s something I always have to remind myself when dealing with seemingly insurmountable mountains,” Ellis says. “That how I advocate for myself as I move through the experience is integral.”

She references the voting rights initiatives that rose from Abrams’ lost gubernatorial race in 2018. “The takeaway of her story doesn’t leave you at the conclusion of a personal or professional grieving process with just your feelings in your hands,” she continues. “Taking action afterward can be the difference between living with something and living with a future outcome that feels even better than what you thought hurt so much at the time.”

— Jill C. Shomer

Stacey Abrams

Creating strategy out of setbacks

NATASHA CUNNINGHAM

Abrams’ 2018 run for Governor of Georgia made her the first Black American woman to become a major-party gubernatorial nominee in the United States. Her loss was one of the most widely reported instances of voter suppression in American history. For others, this might have been the end of a career in politics. For Abrams, it marked the beginning of an even bigger mission to make sure every eligible adult in America is able to exercise their right to vote. Within two years she created the most influential initiative to fight voter suppression in the country and founded a coalition of non-profits to register over a million Georgians to vote in elections for years to come.

Barriers & Bias

Like most women of color, Abrams is familiar with barriers to access. This was not even the first time Abrams had been held back when trying to reach the Governor’s Mansion. When she was made the first Black valedictorian of her high school, Abrams and her family were invited to a dinner for the state’s top students at the Governor’s Mansion. The family traveled by bus, as they could not afford a car. Seeing this, a guard insisted they didn’t belong at this private party. Her parents pushed back and the family were admitted. Abrams doesn’t remember the party, meeting her fellow valedictorians, the governor, or anything else from that day except being turned away at the door.

From Struggle to Strategy

Abrams’ recollection and response to being singled out in high school is one of many examples of how she processes adversity. She has felt the pain and trauma of being undervalued, overlooked, and excluded based on skin color, gender, and income. Once that initial sting subsides, she pivots to analyzing the problem, the contributing factors, and above all, herself to decide how to change it. In this case, it was to one day show the state, and the country, that she deserved to be at the Governor’s Mansion by running for governor.

This hallmark trait of leveraging setbacks is laid bare in every aspect of her life, including money. One of six children growing up in a low-income household, Abrams frequently bore the responsibility of financially supporting her family. With little access to financial literacy or capital, Abrams still had $200,000 in debt during her gubernatorial run in 2018 — $50,000 in deferred taxes and $170,000 in credit card and student loan debt.

Abrams recognized she was not alone in this struggle, noting in an article for Fortune: “Debt is a millstone that weighs down more than three quarters of Americans ... It should not — and cannot — be a disqualification for ambition.” Abrams first began taking on considerable debt to go to college and graduate school. The risk seemingly paid off when she landed her first job after graduating from Yale Law School. Her salary was $95,000, three times her parents’ income combined. However, as Abrams began to pay off those debts, even bigger financial obligations emerged. Hurricane Katrina battered her parents’ community, leaving Abrams to be the breadwinner and provider for her family again. Abrams’ financial strain was exacerbated further when her parents became responsible for her brother’s newborn daughter.

Rather than cast light away from her financial challenges, Abrams put them front and center in her campaign for governor, pointing out that race and gender play a major role in determining just how big of a financial disadvantage we’re likely to face. Understanding the systemic nuances of how and why she found herself thousands of dollars in debt, Abrams used her platform to encourage financial literacy and advise others about what they can learn from her experiences.

Abrams’ unrelenting dedication to deconstructing the barriers she experienced growing up led her to pursue a career in politics in 2006 as the State Representative for Georgia’s 89th district. Growing up with Methodist pastors as parents, Abrams knew how to connect with congregations of all sorts, including policy makers and voters. She brought everything learned in church to the halls of the Georgia State Capitol — whittling big ideas and political jargon down to the basics of how policies affect the everyday lives of the people she represented. She was so skilled, her fellow representatives on both sides of the aisle would ask her to review their bills before presenting them.

In 2014, Abrams created the New Georgia Project, a voter registration program to make voting more accessible to people of color ahead of the senate election that same year. Abrams led the organization part-time while still holding office. The small but ambitious organization registered roughly 69,000 new voters in its first year.

In 2017, Abrams stepped down as minority leader to run for Governor. Her opponent, then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp, was in charge of voter registration. In July 2017, Kemp purged more than 500,000 voter registrations, the largest mass disenfranchisement in US history. Between 2012 and 2018, Kemp canceled 1.4 million voter registrations, using tactics that date back to American Jim Crow laws. In most elections, a winner is decided within 24 hours of election day. For Abrams, this process took ten days. She describes the days between the election and formally stepping out of the race as compounding stages of grief hitting her all at once. Voter suppression hotlines managed by her campaign and nonprofits banked over 80,000 calls from Georgians whose ballots were not counted, or whose names were purged from the voting rolls. “Until this election, I had never considered myself an angry person,” Abrams would later write.

Propelling Pain

By the sixth day, still in the heat of a legal battle, Abrams again pivoted to analyze the root of the problem to decide what to do next. Still grieving, she decided to add another stage to the mourning process. It’s called plotting. Some of us heal through a drawn-out grieving process that ends in acceptance. In Abrams’ case, accepting defeat also meant accepting inequality. Plotting offered a new path where healing and making the difference you want to see in the world can make perceived failures integral to future successes. She grabbed the nearest legal pad and began to write out what would later become a coalition of organizations dedicated to ending voter suppression, disenfranchisement, and inequality. Abrams’ newly reclaimed purpose made her path forward clearer than ever despite being in the midst of an unbearable loss.

On November 16, 2018, Abrams ascended the stage one last time as America’s first female Black American gubernatorial candidate not to concede, but to announce the beginning of a mission to uphold a right her enslaved ancestors died fighting for: the right to vote.

Despite narrowly losing to Governor Kemp, Abrams received more votes than any Democrat in Georgia election history, including President Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton during their presidential campaigns. Abrams’ run became an inflection point for voter turnout among Latinx, Asian, and Black American voters. That progress would serve a multitude of purposes through the creation of Fair Fight Action and Fair Fight PAC to tackle voter suppression, Fair Count to address the census and beyond, and the Southern Economic Advancement Project, and bolstering New Georgia Project’s voter registration drives. For Abrams, winning a single election is not a victory; ensuring that every election is a true reflection of the will of the people is.

Excerpted from We Go High by Nicole Ellis reprinted by permission of DK, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Text Copyright © Nicole Ellis, 2022.

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu