|

|

|

COVER STORY

A Wintertime Soldier

Clarence Jones ’53: Lawyer, speechwriter, adviser and confidant to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

By Evan J. Charkes ’82

Jones was a political science major who played football and was politically active during his time at Columbia.

Photo: DANIELLA ZALCMAN ’09

In April 1960, Clarence Jones ’53 was cozily ensconced in the American middle class. A young attorney in a small Los Angeles firm, he was married and had one daughter. His wife, Anne, was pregnant with their second child, and the family lived in a suitable house in Altadena, Calif.

All that changed with a phone call.

Earlier that year, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been indicted in Alabama for felony tax evasion, for committing perjury by signing tax returns that did not report all of his income. A conviction of King in an Alabama state court would have meant a long prison term and might have permanently derailed the Civil Rights movement.

King sought legal help from NAACP Board members, including a New York City judge, Hubert T. Delaney, who wanted an African-American lawyer to help the trial. “They had lots of white lawyers who wanted to volunteer, from the ACLU. But Judge Delaney wanted a Negro lawyer who would be responsive to the needs of the [civil rights] movement. Little did he know,” Jones says, chuckling.

Delaney, who had gotten Jones’ name from a mutual friend and attorney in New York, Arthur Kinoy, called Jones in his Altadena home one evening. With a wry smile, Jones, who wears tinted glasses and a single hoop earring, recounts the conversation.

“‘Clarence, I know that you are just starting out, but Dr. King has been indicted for tax evasion and we need someone to essentially be a law clerk and go down to Montgomery and work for maybe six weeks, do the research, write the motions and so forth.’” Though flattered, Jones declined, and continued to decline when Delaney restated his request.

Later that day, Delaney called Jones again and told him that King was coming to Los Angeles to speak at the World Affairs Council. He thought it would be a good idea if King stopped by Jones’ house to talk. Jones agreed.

“The house that we lived in at the time had a retractable ceiling. You pressed a button and the ceiling opened and you could see the Sierra Madre mountains and the stars. So it was into this setting that Martin Luther King came to my house. He said to me, ‘Pretty nice house you have here, Mr. Jones.’ We sit down. My wife, Anne, was very accommodating, putting little things out to eat, getting drinks. Dr. King started telling me about things going on in the civil rights movement. So I sat there and listened.

“He said: ‘I know you come from the North and not from the South. We have a lot of white lawyers but we don’t have any Negro lawyers. We need Negro professionals who can help us.’ I said, ‘Dr. King, I really would like to help you, but I really can’t go to Montgomery.’

“Martin looked straight at me and said: ‘Tell me something about yourself.’ So I told him that my mother was a cook and a maid, my father was a chauffer and gardener, that before the age of 6 I was put in two different foster homes because there was no place for my parents to keep me, and then put into a Catholic boarding school.

“And then, he leaves. My wife is really angry at me. She says, ‘What are you doing that’s so important that you can’t go down there? What are you doing?’ My response was, ‘Anne, just because some Negro preacher got his hand caught in the cookie jar, that’s not my problem.’”

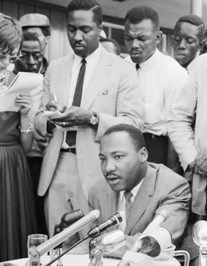

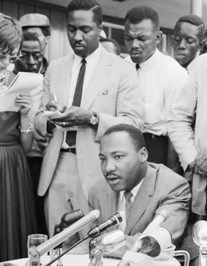

Jones takes notes at a press conference given by civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. regarding an agreement reached on a "limited desegregation plan" outside the Gaston Motel in Birmingham, Ala., February 1963.

PHOTO: ERNST HAAS/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

Jones pauses for a moment to let the words sink in. Then, he picks up the story. “I got a call the next day from Judge Delaney. He said that Dr. King wanted to invite me to hear him preach at the Baldwin Hills Church in Los Angeles. Dr. King was going to be a guest preacher. My wife said to me, ‘You’re going to church. You are going.’

“When I got to the church, I was ushered to my seat toward the front. Martin gets up at the pulpit. Now, I had never heard him preach before.” Jones then begins a spot-on impression of King.

“‘The text of my sermon today is the role and responsibility of our professional Negroes to help the masses of our people.’

“I thought that was an interesting subject. King goes on and gives the most eloquent description of what he was trying to do in the South.” Jones then returns to his King-voice. “‘And for example,’ he says, and then pauses. Now, Martin Luther King was the most erudite, most brilliant orator that I had ever seen. But at the Baldwin Hills Church, he went into this feigned theatrical stutter.

“‘Now … now … now … my friends in New York, they tell me that there is a young man, a young man sitting in this church this morning. My friends tell me that the Good Lord has touched this young man’s brain. That when this young man goes into the law library and does research that he can go all the way back to 1066, to the Magna Carta, and find anything there is to find. And when he finds them, he writes them down, and the words are so … compelling. And this is a brilliant young lawyer I am told.’

“And King pauses before adding, ‘But this young man has forgotten from whence he came.’

“Now, I am sitting there wondering who he might be talking about. But then he starts telling the congregation about my life — things that I had told him in my house a couple of days before.”

Jones’ voice softens. “Then Martin begins to quote a poem by Langston Hughes [’25], Mother to Son. The poem is about a Negro woman washing the staircase in a white folks’ house, and as she pauses at each level, she says, ‘I am doing this for you, son, life ain’t been no crystal stair.’

“As King begins to tell the woman’s story through the poem, I began to cry. Like a video, I could see my mother in her uniform. It was very moving.

“Then the service is over. Martin is standing by the steps near the pulpit. He looks over at me, and he has this look on his face, like a Cheshire cat. And I don’t say anything. I walk over to him.”

Jones continues in his King-voice. “‘You know, Mr. Jones, I never mentioned your name. But preachers, we need examples to prove our point.’

“I extended my hand, and simply said, ‘Dr. King, when do you want me to leave?’”

Jones looks up again, a broad smile across his face. “That was the making of a disciple.”

During the next eight years, Jones would become a lawyer, speechwriter, adviser and confidant to King and an integral part of epochal moments, including King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” the “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington and King’s famous speech on the Vietnam War delivered at Riverside Church. Their close relationship lasted up to King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

After King’s assassination, Jones’ business career flourished. He was a partner with the Wall Street firm Carter, Berlind & Weill (a Citigroup predecessor) and the first African-American Allied Member of the New York Stock Exchange. As an investment banker, he served in the late 1960s and early 1970s as an adviser to the governments of Jamaica, Zambia and the Bahamas. Jones was an executive with Inner City Broadcasting, which was owned by Percy Sutton. He also was publisher of The Amsterdam News, and, at the request of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, helped negotiate an end to the Attica prison inmate rebellion.

Jones now is an executive adviser to Marks, Paneth & Shron, a New York-based financial services firm. Since September 2006, he has been a scholar-in-residence at Stanford’s Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. Jones is a frequent lecturer on King, speaking at public events as well as at corporations such as Citigroup, General Electric and Pfizer, and has completed a book about King that will be published later this year.

Born in a North Philadelphia hospital in January 1932 at the height of the Great Depression, Jones grew up an only child. His father, Goldsboro Benjamin Jones, had a fourth-grade education and was a chauffeur and gardener for a wealthy family, the Lippincotts. His mother, Mary Tolliver Jones, who had an eighth-grade education, was a maid and cook for the same family. Jones’ parents lived in the Lippincotts’ home in Riverton, N.J., during the week and stayed with friends and relatives on their days off. Without a home of their own, they placed their son in a foster home soon after he was born.

When Jones was 6, his parents sent him to Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People, a Catholic boarding school in Cornwell Heights, Pa. “I was raised by these Catholic nuns,” remembers Jones. “If I had been in a public school in New Jersey at that time, it would have been segregated. This was different. The nuns grounded me in Latin and English grammar. I can still remember going to the chalkboard in the front of the classroom and diagramming a sentence. And, of course, I became a Catholic. I was an altar boy and went to midnight Mass.”

When he was 15, Jones’ parents secured a home of their own, so he returned to Riverton. At Palmyra H.S., he graduated near the top of his class, was selected as class speaker at graduation and was president of the Honor Society. “I was also voted the ‘Person Most Likely to Succeed’ and the ‘Most Outstanding Student.’ There’s a picture of me in the class yearbook next to a globe that says ‘Tomorrow, the World.’ ”

There was one problem about conquering the world: Jones was too poor to go to college.

“Columbia will always be special in my heart because of what Dean Coleman, the professors and my friends did for me when my mother was sick. ”

Instead, he enlisted in the Navy at the beginning of his senior year of high school, thinking that the Navy would pay for his education. But his misrepresentation of his age was discovered by the recruiting officer. “My principal went bananas. He then got some of my teachers together — I remember specifically my science and speech teachers — and they raised some money for my college applications. They sent away for the applications: University of Pennsylvania, Columbia, Syracuse, Yale and Princeton. I was able to get into all of these schools. Syracuse offered me a music scholarship, but Columbia gave me the most financial assistance. That’s how I ended up selecting Columbia.”

When he got to Morningside Heights in fall 1949, the 17-year-old Jones was one of a handful of African-American students. “The College had about 3,300 students, and there were very few African-Americans. And I had nothing in common with them — they were all middle class, the sons of lawyers, doctors, a university president.”

Jones lived in Hartley Hall his first year and played football, as a halfback, under legendary coach Lou Little. “I loved Lou Little. I remember his gravelly voice; he would say to me: “’Jonesie boy, you’ve got to play football, at least you’ll get one good meal [from the training table].’” Jones also ran track and Little told him that “the only way you’re not going to get hurt playing football is to run as fast as possible.”

Jones was a political science major; his favorite professor was Charles Frankel, and his favorite course was on British constitutional history. He also remembers taking a chemistry class with Nobel Prize-winner Linus Pauling, who “terrified me. I was the only black in his class, and I would try and sit in the middle to the back of the class. Pauling would say: ‘Mr. Jones, we would like to see you, please come nearer.’ And I would end up moving to the front of the class.”

During the middle of his junior year, Jones’ mother was diagnosed with rectal and colon cancer. “I remember it was January 8, my birthday. I was taking an exam and the proctor told me I had a call. It was my mother’s doctor, and he told me that my mother had an operation and they found cancer. The doctor said I should come to see my mother, who did not have more than a few months left. I was devastated. I went to see Dean [Henry] Coleman [’46], and my first reaction was to drop out of school. I wanted to spend time with my mother. Dean Coleman told me that he didn’t think I should drop out, and he worked with my professors to arrange for me to get my assignments while I was home with my mother. I needed to maintain a B- average to keep my financial assistance. I spent the whole semester doing that. My friends took copious notes and sent them to me from my classes.

“Columbia will always be special in my heart because of what Dean Coleman, the professors and my friends did for me when my mother was sick. She died in May. I don’t know if what they did was legal, but they made it work.”

Jones also was politically active at Columbia, a member of the local chapter of the NAACP and the Young Progressives of America. “The YPA got mad at me because they would go out on Saturdays and hand out leaflets on 116th and Broadway, and I couldn’t be there because I was playing football. I remember meeting Paul Robeson at a party. Robeson said to me: ‘Young man, you go back and tell those students that you spoke to me. You tell them that if a Negro scores one touchdown on a Saturday afternoon at Baker Field, that has more impact than anything they could possibly do with their leaflets. Even segregationists and white racists applaud good sports performances.’

“I never forgot that. Of course, I never scored a touchdown, but he had a good point,” Jones says, laughing.

Three months after graduation, Jones was inducted into the Army — the Korean War was in full swing. He refused to sign any papers during his induction, however, and was given “Holdover” status when he reported to Fort Dix, N.J., with other inductees. He ultimately served 21 months but the Army discharged Jones, for, among other reasons, failing to sign the Loyalty Oath. “I was prepared to serve the country once the country was prepared to treat me with all of the rights and privileges of any other citizen,” Jones says. With the ACLU’s help, he gained a reversal from the Army Discharge Review Board and turned it into an honorable discharge.

Jones then went to law school at Boston University and received financial assistance through the Korean GI Bill. A love of copyright law was further fostered by a BU professor who encouraged him to go into entertainment law and helped land him a job in Los Angeles. He had only been at the law firm for four months when he got Delaney’s call.

One week after Jones heard King at the Baldwin Hills Church service, he said goodbye to his family and flew to Montgomery, Ala., to help King’s legal team prepare for the trial, which took place in May 1960. In a shocking decision, the all-white Alabama state jury acquitted King of perjury charges.

Jones became committed to the civil rights movement full-time. He left his Los Angeles law firm, moved his family to New York — they settled in Riverdale — and became a partner in Lubell, Lubell & Jones, as well as the general counsel for the Ghandi Society for Human Rights, the nonprofit organization set up to aid King in his ongoing litigation. One of the first legal matters he worked on was The New York Times v. Sullivan, a seminal First Amendment case that arose out of an advertisement in the Times designed to raise monies for King’s defense in the Alabama perjury trial. Jones also began to do more day-to-day work for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Harlem office, working closely with Stanley Levison, a King confidant.

While traveling with King, the two young men began to form a close bond — King was just three years older than Jones, and also had young children. Jones remembered one trip in 1962 to Albany, Ga., in particular.

“We were sharing a room in the home of the leaders of the Albany Movement, Martin was sitting on one of the beds in the room, untying his shoes. He looked up at me and said: “You know, Clarence, you and Stanley (Levison) are like wintertime soldiers.’

“I looked at him quizzically, and before I could speak, Martin continued. ‘Anyone can stand with you in the warm summer sunlight of August. Only a wintertime soldier stands with you at midnight in the alpine chill of winter.’

King, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, addresses thousands of civil rights supporters during the March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Jones helped write King's famous "I Have A Dream" speech and copyrighted it, to the lasting benefit of King's estate.

PHOTO: AP PHOTO

“When I finally understood what he had said, I began to choke up and I said something to the effect that I didn’t know whether or not I measured up to that description. Years later, I concluded that Martin, as well-read as he was, must have been thinking about Tom Paine’s famous words in 1776: ‘These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.’ ”

As the civil rights movement pushed ahead, Jones played an important role for King, first as a lawyer, then as a fundraiser, mixing easily with the moneyed classes in New York and Los Angeles, and then as one of King’s inner circle of advisers. When King was arrested in Birmingham in April 1963, during the infamous demonstrations involving Sheriff Bull Connor, it was Jones who went to see King and smuggled newspapers into King’s jail cell. The Birmingham News, in particular, carried stories of white clergymen rebuking King and the protestors.

“The first time I saw him in jail, I could see he was very agitated. There was writing on the edges of his newspaper. I asked, ‘What’s that?’ He said: ‘Clarence, we have to answer this.’ ”

As Jones told historian Taylor Branch for Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 (1988), King slyly pulled the papers out of his shirt and told Jones to “get it out, if you can.” Jones, however, thought the “letter” was just an “indistinct jumble of biblical phrases wrapped around pest control and garden club news,” a “distraction” from the legal issues and money woes that he wanted to discuss with King, who spent most of the visit explaining to Jones how to decipher the various arrows and loops in the margins. Jones gave King some yellow sheets of paper and then smuggled the “letter” under his own shirt and out of the jail.

“Anyone can stand with you in the warm summer sunlight of August. Only a wintertime soldier stands with you at midnight in the alpine chill of winter. ”

King continued to write on the yellow sheets that Jones had provided. These words were then typed up and returned by Jones to King, who ultimately wrote a 20-page document known as the “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in which he eloquently and forcefully answered the white clergy. More than 30 years later, Jones was honored by President Bill Clinton with a citation for his role in bringing forth the historic document.

By July 1963, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had taken notice of Jones. Hoover sent a memorandum to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy asking that wiretaps be placed in Jones’ law office, at the Gandhi Society and at his home. These wiretaps were not subject to judicial request or approval. Hoover’s stated rationale was that Jones had “recently been in frequent contact with Communist Party, USA, leaders in New York City concerning racial matters.” Kennedy signed the wiretap request on July 23, 1963. Jones keeps a copy of the order, which he obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request.

For more than four years, the FBI kept continual 24-hour wiretaps on Jones, something he now counts as a blessing since he is using those wiretaps to confirm his recollection of events for the book he is writing on King. “I want to give a note of public gratitude to the FBI,” he says. “How do I know something happened? I just read the transcripts.”

Jones played another critical role in perhaps King’s most famous speech, “I Have a Dream,” delivered on August 28, 1963, at the March on Washington — an event for which Jones helped King prepare.

“On August 27, we were sitting in the lobby of the Willard Hotel, and Martin asked us for some ideas of what he should say,” Jones recalls. “Everyone gave him some ideas. (People in the lobby included, among others, Ralph Abernathy, The Reverend Bernard Lee, Walter Fauntleroy and Cleveland Robinson.) I was asked to take notes. Martin asked me to go upstairs and prepare a draft for his reference. I left the lobby and went upstairs to my room to organize my notes and then prepared a comprehensive summary draft. I crafted an analogy of people coming to the March to redeem a promissory note or check for justice and freedom, which had been returned, marked ‘insufficient funds.’

“Four months before, I had met Nelson Rockefeller at the vault room of the Chase Manhattan Bank to collect $100,000 to post bail for 100 or more children who had been arrested for participating in demonstrations. When they opened the large vault, I was given the money, and then a promissory note to sign. Later, the note was cancelled by Rockefeller. It was his way of quietly helping the movement. This action made a large impression on me.

“I then went downstairs and began to read a summary of the various points made earlier. People started throwing around more ideas. Martin got up, somewhat exasperated, and he said: ‘Gentlemen, thank you for your help, I am going upstairs and counsel with the Lord. I will see you in the morning.’

“I got up at 5 a.m. on August 28. Dora MacDonald, who was Martin’s secretary, told me that Martin’s speech was being mimeographed for insertion in envelopes as part of the press kits. When I got to the press tent, I looked at the speech — about 40 percent was what I had written, and the rest was Martin’s. Then I noticed that there was no copyright notation on the speech. I always said to Martin: ‘You just give things away, people come and take advantage of you.’

“Now, I can’t take any claim for any brilliance, but the light bulb went on: This could be an important speech. I made some people take the speech out of all of the envelopes, and on every page of the speech, with some assistance, I put a little ‘©’ on every page, with a ballpoint pen. The concept was that you have your common law copyright unless you lose it by some form of mass distribution.”

With the copyright © on each page, Jones then went to the site of the speech. “There had been a dispute about the order of who was going to speak. Many people didn’t want Martin to go last. I had been the heavy, his negotiator. I said if Martin Luther King does not speak last, then he does not speak. At which point, I got a call from Martin, and he told me that I shouldn’t say that. ‘You’re going to make them think we have some kind of ego.’ I said to him, ‘But I know why they are coming to Washington. They’re here to see you.’

“Now, at the time that Martin was delivering the speech, I was about 15–20 yards away to his rear upper left. And as I listened, I heard him cover the parts that I had written, including the promissory note not being redeemed. Then Martin paused. He grabbed the podium, leaned back, turned the text over and looked out at those hundreds of thousands of people. And I said to the person next to me: ‘These people don’t know it, but they are about to go to church.’ And that’s when Martin did his peroration about ‘I Have a Dream.’ After he had finished, I walked up to him and said: ‘Martin, you were smokin’, just smokin.’ ”

Soon after the speech, Jones filed an application for a copyright of the “I Have a Dream” speech. Jones has a copy of the actual copyright certificate, granted October 2, 1963, and the letter he wrote to MacDonald, enclosing the certificate. Jones looks at the letter’s last paragraph and reads: “If ‘I Have a Dream’ is as significant as the press and general public acclaim has indicated, the total value of these rights reserved, measured against the potential market for their economic exploitation, is conservatively, in the thousands of dollars.”

Today, Jones smiles at that estimate. “The touchstone of the King Estate, by far their biggest moneymaker, has been, and is, the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. I sometimes think if I made no other contribution, then at least I did that for Martin. I feel very proud of that one.”

One month after the March on Washington, four young girls were killed in Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Recalls Jones: “I thought that the bombing was the Klan’s answer to the March on Washington. After the March, everyone was on such a high. Martin was on such a high. Martin said to me: ‘Everybody is talking about the great speech I made.’ I said to him: ‘We haven’t seen the backlash yet.’ After the bombing, I told him this was their answer to the March, that they wanted to send a message. When Martin spoke at the funeral for those girls, it was the first time I saw him cry in public.”

Jones continued to write speeches for King. “I got so I could hear his voice in my head. I knew the cadence in which he spoke, and I would write to that cadence.” Jones knew he was in an unusual place. “Martin told me once that he had gone to an academic retreat and someone came up to him and said, ‘I understand that you have a young lawyer from New York writing your speeches, who you rely on. You need a professional speechwriter.’ Martin replied, ‘Clarence would be the first person who would agree with you. Clarence may not be a professional speechwriter, but he has one characteristic that the people you recommend for me don’t have.’

“‘What’s that?’ asked this person.

“‘I trust Clarence,’ Martin answered.

“I never forgot him telling me that,” Jones says softly.

Jones also got to know Malcolm X, and often acted as an emissary between him and King. “During one of my several meetings with Malcolm X, he would rhetorically ask me, ‘Brother Jones, don’t you know the way in which the white power structure deals with an authentic revolutionary black leader? First, they try to show you the errors of your ways. And as part of their process they may give you goodies, like appointments to government agencies. If that doesn’t work, then they try and discredit you, showing your alleged transgressions, personal deficiencies and lack of integrity. If either of these two measures don’t work, they then kill you.’”

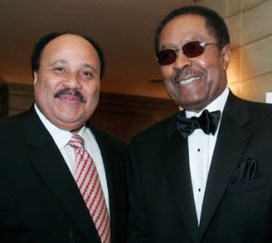

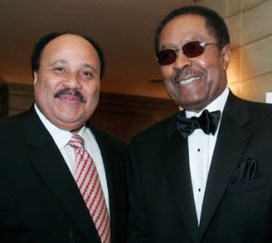

Jones (right) is joined by Martin Luther King III on March 1, 2006, in New York, when Jones was presented with the American Jewish Congress' "Isaiah Award" for his contribution to the civil rights movements and helping bridge the gap between Jews and African-Americans in the United States.

Photo: AP PHOTO/DIANE BONDAREFF

Jones was on his way to the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem to hear Malcolm X speak on February 21, 1965, the night Malcolm was assassinated. “I had pulled off the highway and was headed over there when I heard the reports on the radio. I couldn’t believe it,” Jones says.

As for how King felt about his personal safety, Jones says: “There wasn’t a day that Martin Luther King didn’t wake up and think it was his last day. You and I walk down the street and a car backfires and we wouldn’t pay it attention. He would walk down the street and a car would backfire and he would go like this [ducks his head]. Martin never believed he would live to be an old man. He just didn’t know when it would happen. Martin was afraid, but he was fearless. There’s a difference.”

On April 4, 1968, King was assassinated by James Earl Ray in Memphis. King had called Jones the night before to make sure he was coming to Memphis. Hours before his death, King called Jones at his office but Jones was on another call and didn’t speak with King. “I often said to Sandy [Weill], ‘What was I doing that was so important that I could not take a call from Martin?’ That really bothered me.”

After more than 40 years, Jones now is telling his story, deliberately having waited until the death of Coretta Scott King, who died on January 30, 2006.

“In my book, I make judgments about certain African-American leaders and I did not want them to call her up and talk about it,” he explains. But he also cites the trust he had with King, who he believes did more to achieve social justice than almost any other person in American history.

“When he and I were together, he had reason to believe that this was going to stay between us,” says Jones. “There are still topics I won’t talk about, such as Martin’s personal life. However, if you want insight into the man, read my book.”

Jones’ book, currently titled What Would Martin Say? Reflections on the Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr., is due to be published by HarperCollins in April.

Evan J. Charkes ’82 is a deputy general counsel for the Global Wealth Management business of Citigroup in New York City. He lives in Westchester County with his wife and three children.

|

|

|