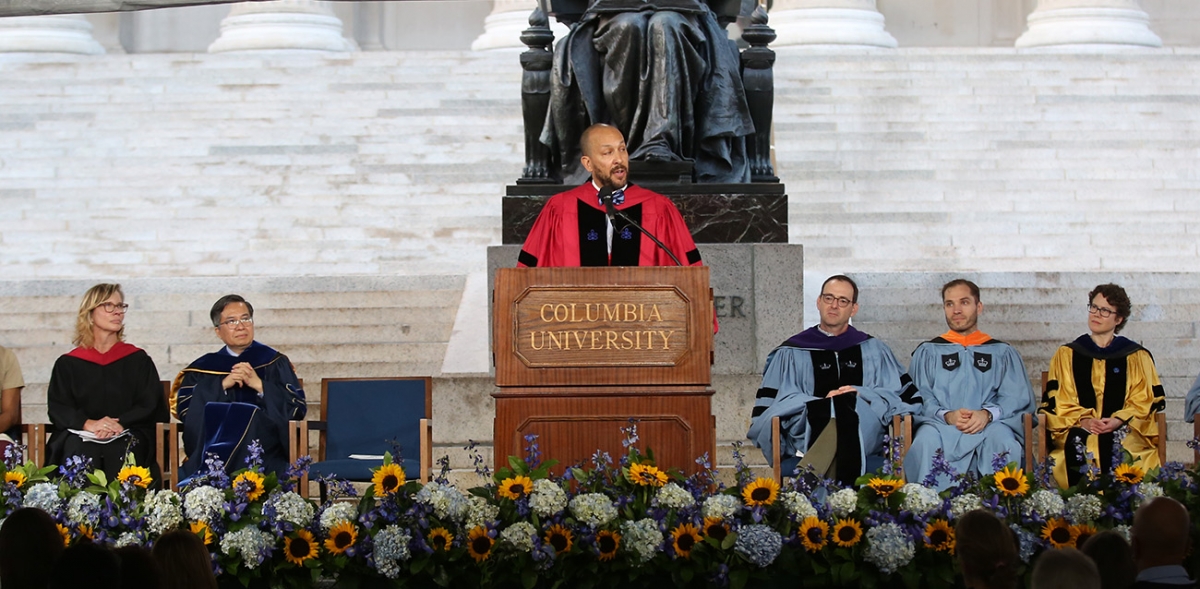

Diane Bondareff

At Convocation on Sunday, August 28, 2022, Dean Josef Sorett delivered his first remarks as dean to the incoming Class of 2026 and their families. This version has been edited for clarity.

Let me echo Dean Marinaccio and my colleagues on the stage in expressing my appreciation to President Bollinger, and to all of the faculty, staff and alumni who have joined us this evening — a veritable crowd of Columbia witnesses assembled to welcome the newest members of our community. What could be more inspiring or more exciting than to be the “we” that we are together tonight.

To the Class of 2026, parents, families and friends, I am so pleased to offer my own welcome on behalf of Columbia College and congratulations to you on arriving at this moment of new beginnings. I am honored and privileged to start my own journey as dean of Columbia College and vice president for undergraduate education alongside yours. This occasion provides an opportunity to reflect on our shared purpose and the curiosity and questions that drew us to New York City, to Columbia and to Low Plaza specifically, this evening.

When I started college I did not know what it meant to be an academic — I thought I knew what I wanted to study, which is not what I teach today, but I was there because I wanted to play basketball. I certainly never expected to become a professor at a place like Columbia, teaching courses on race and religion in American culture. Not exactly the lightest of topics these days, or ever. As I think is often the case, my professional journey — that is, my path to the professoriate and now to the dean’s office — began with a more personal, yet rather mundane and unexceptional set of everyday experiences.

As a Black boy growing up in Massachusetts, shuttling back and forth between the city of Boston and small-town Lincoln throughout much of my childhood, I learned to navigate through a set of places and of social spaces that reflected the complicated histories of race, as well as religion, that shape our contemporary world. The various kinds of difference — be it of culture or economic class — that defined these contexts proved formative not only as I came of age as a young man but also, eventually, in shaping so many of the questions that preoccupy me to this day as a scholar.

When I landed in Tulsa, Okla., for college in August of 1991, my freshman-year roommate had grown up on an apple farm in rural Ohio in a space that, we’ll just say, was homogeneous in cultural and racial terms. That year our dorm room became a space of vibrant exchange between us and our varied circles of friends — which were largely Black and white, respectively. We talked late into the hours, not just about race but about the significance of the cultural and social worlds that shaped us — that we brought to campus with us and that did or did not connect in ways that made sense to us. We didn’t solve any big problems, and the climate on campus was contentious at times, particularly in the absence of any institutional space to talk about these issues. A profound set of questions and tensions emerged in those conversations, and during my years as an undergraduate, I steadily found myself wanting to explore these dynamics in a deeper and more sustained way.

What I found in academia, several years later, and through a circuitous journey, were the space and language to pursue my questions with purpose and rigor, as well as a passion for teaching and learning with and from my students. What I continue to carry with me is a conviction that academia and the academic setting can and must be a source and site of social change in service to the communities from which all of us come. New knowledge must stretch beyond the boundaries of disciplines and the classroom to engage with the social world on and beyond our campus. At its best, Columbia College and the larger university community is such a place, and the holistic nature of the College’s mission embodies many of things that I’ve been thinking about and committed to for a long time.

As dean, my most important responsibility is to steward the education and experience of our students — to ensure that they, that you, have that space and language to ask questions, and to take risks and make mistakes as they are making sense of the world around them. But also to imagine who they might become and what this world could otherwise be. Doing so requires cultivating a respect for the legacy of generations past; a commitment to safeguarding traditions, but also to opening up space for innovation for generations to come. A delicate dance indeed between continuity and change — ensuring that what we provide to our students today is just as transformative as it was for those who preceded them at the College.

All of us today, here, are a vital force in shaping that legacy and tradition. Through the Core Curriculum our students become part of something much bigger than the individual — an intellectual community and an educational experiment in progress for more than a century.

This past year I had the distinct experience of teaching “Introduction to African-American Studies” — a relatively new addition to our Global Core — in the morning; in the afternoon, I found myself in the classroom with 22 sophomores in Contemporary Civilization — the oldest element of the Core. Across these two classrooms a range of questions were surfaced by your peers: about equality, authority and difference, but also about changing technologies, community, creativity and so much more. I watched them refine their questions and work through what the answers might mean — for who they are, for how and where they fit on this campus and in the broader world. Helping students answer these types of questions is at the heart of what the College does, and who we are as a community.

You are about to embark on an undergraduate experience long defined by a commitment to dialogue, to diversity of thought and exploration. You must learn for yourself what kind of student you will be, just as I am beginning to learn what kind of dean I will be. We will teach and learn so much from each other. You will encounter, discuss and debate enduring ideas that will challenge you and your professors. You’ll gain knowledge, understanding, insight and empathy. And your views of yourself and the world will rightfully evolve.

Along the way, I encourage you to engage fully with faculty, advisers, mentors, administrators and alumni. Tell us what is important to you. Show us what you are passionate about. We are here to help you make the most of your academic and cocurricular life. Above all, I hope that you will commit yourselves to engaging with each other. Give each other the space, attention, patience, empathy and respect required for the intellectual and interpersonal journey you are embarking on.

The questions you will ask of yourselves, your professors and each other — those questions and the answers you find will ripple out into the communities you will build and sustain beyond the Gates and long after graduation. The communities you form and the questions you pursue will, no doubt, change our community and the world.

But that comes later. We’re here now, together, at the beginning.

I would like to close with a brief word to all the parents and family members. As a father, I understand what it means to trust the care, safety and education of your children to others. The joy of seeing them thrive and the apprehension of letting go, and about giving them the space to do so on their own terms. Our responsibility to them, and to you, is not taken lightly by anyone on this stage. We thank you for your trust, for kindling the fire of curiosity in your children, for creating a stage for them to launch from and for the abiding love and support that will sustain them in years to come.

And so, Class of 2026, I look forward to seeing you on campus in the days and weeks ahead as we are beginning our adventure together. But for now, I will leave you with my respect and sincere excitement for the journey ahead. Good luck and let’s go!