If you know of a Columbia College student, faculty member, alumnus/alumna or program we should spotlight, or if you would like to submit a story, please contact:

Columbia College

Office of Communications

cc-comms@columbia.edu

“Lamont is more than a research haven. It is my meditative retreat to unwind and reset, to think and to push my limits.” — Tianjia Liu CC’17

Starting in Fall 2014, Tianjia Liu CC’17 began a weekly commute to conduct research at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, the research campus located in Palisades, N.Y., that is used by the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and its affiliate, The Earth Institute. Tianjia’s research was made possible by the Center for Career Education’s Work Exemption Program, a part of Columbia’s enhanced financial aid program that is designed to enable financial aid recipients to take advantage of unpaid experiential learning opportunities. Selection for WEP is competitive and accepted program participants receive a grant to support the pursuit of unpaid internships, research projects and community outreach conducted locally, nationally and internationally. Here, Tianjia reflects on her research and her time spent in Lamont’s tranquil environment.

Though just a 40-minute shuttle ride from Columbia’s Morningside Heights campus, few Columbia undergraduates visit the renowned Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, the research campus used by the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and its affiliate, The Earth Institute. Located in Palisades, N.Y., the observatory is otherworldly compared to Morningside Height’s interlocking network of towering, stately buildings, its deceptively modest one- to three-story buildings nestled in forests, hiding the high tech inner workings of the laboratories housed within. Lamont is home to serenity itself. In autumn, crispy red, yellow and brown leaves pepper its sprawling grounds, turkeys lazily stroll behind the library and water snakes lounge on the lily pads in the rose garden. In winter, large icicles dangle precariously from roof edges, while in spring and summer red roses bloom and seeds disperse from cottonwood trees as Lamont scientists resume weekly midday-work games of volleyball, soccer and basketball on the campus’ green lawns. Year-round, because of its liberating rural feel, Lamont exudes a sense of timelessness and remove.

Tianjia Liu CC’17 gives a poster presentation to Lamont faculty, parents and students while a part of the Lamont Summer Intern Program. Photo: Melissa Seto CC’16

Tianjia Liu CC’17 gives a poster presentation to Lamont faculty, parents and students while a part of the Lamont Summer Intern Program. Photo: Melissa Seto CC’16

I first visited Lamont in the summer of 2014 when, as part of the Lamont Summer Intern Program, I researched the North Pacific paleoclimate using Alaskan sediment cores, working to create a record of the past 6,000 years. Seeds, pollen, dust flux and organic compounds in leaf waxes can be used as proxies, which are preserved physical characteristics that can be used to measure changes over time. These proxies act as time capsules, allowing botanists and bigeochemists to reconstruct a record of past vegetation and climate. I, along with my mentors, Jonathan Nichols, assistant research professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and Dorothy Peteet, adjunct professor of earth and environmental sciences and a NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) senior research scientist, hope that our terrestrial record can act as a weather gauge for North Pacific wind conditions during the Late Holocene Epoch, which encompasses the last few thousand years. Because North Pacific marine productivity — or the rate at which new biological material is produced, mainly through photosynthesis in the ocean's surface layer — is limited by iron deficiency, we want to understand which climate conditions are optimal for wind to carry iron from the land to the ocean, namely, from the Copper River Basin in Alaska’s southeast corner to the North Pacific Ocean.

In Fall 2014, thanks to funding from the Center for Career Education’s Work Exemption Program (WEP), I continued to work on and subsequently presented my project at the 2014 American Geophysical Union (AGU) conference, held for a week every December in San Francisco.

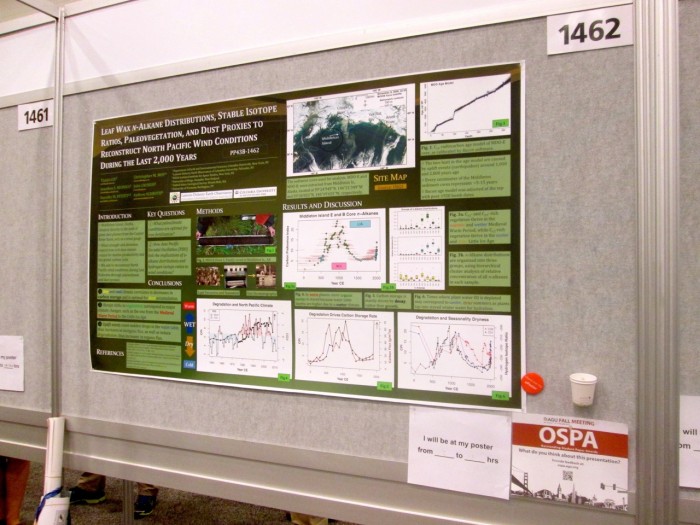

Tianjia Liu CC’17’s poster at the 2014 American Geophysical Union conference. Photo: Tianjia Liu CC’17

When my flight landed in the mist of the rain-drenched San Francisco hills on December 14, 2014, I was anxious but ecstatic. At the Moscone Center the next morning, overwhelmed and more than a little lost, I roamed the poster halls, sat in at a conference and on several talks, and proceeded to marvel at the fact that I would be presenting my research along with thousands of scientists, experts in their respective fields, who were all there, in one place, at one time. On Wednesday, the night before my poster session, I retreated to the hotel gym and recited my spiel past midnight.

Tianjia Liu CC’17’s poster at the 2014 American Geophysical Union conference. Photo: Tianjia Liu CC’17

When my flight landed in the mist of the rain-drenched San Francisco hills on December 14, 2014, I was anxious but ecstatic. At the Moscone Center the next morning, overwhelmed and more than a little lost, I roamed the poster halls, sat in at a conference and on several talks, and proceeded to marvel at the fact that I would be presenting my research along with thousands of scientists, experts in their respective fields, who were all there, in one place, at one time. On Wednesday, the night before my poster session, I retreated to the hotel gym and recited my spiel past midnight.

The next morning, I hurried to the Moscone Center to hang up my poster in the “Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology” row. Thursday afternoon saw me nervously fidgeting in front of my poster as people walked by, then gesturing animatedly to explain my project to the researchers huddled in front of me. Conversations flowed from question to suggestion to proposition, and after my presentations, many of those I spoke with were surprised to hear that I was only an undergraduate, let alone just a sophomore. I smiled. Despite my relative inexperience, they continued to talk to me like a scientist, like I was one of them. At first, I was simply glad to discuss my work at a professional meeting, but I left AGU telling myself, “I have to come back.” The conference affirmed my desire to continue my research, to share it with others and to explore work in other scientific fields.

Thanks once again to WEP, I spent Spring 2015 back in the lab at Lamont, my project far from over. But AGU had made me look forward to the work awaiting me more than ever. Perhaps I spent the semester a bit too eager to fast-forward our team’s progress. Patience, I reminded myself each week as I rode the shuttle to Lamont from Morningside Heights. As I mused over research papers, my eyes often weary, my patience stretched like a tightrope bridging two crumbling ledges, I reminded myself that this was par for the course. Moments like these plague researchers. Throughout my time conducting research at Lamont, I would watch as the faces of the researchers I worked with slackened, their eyebrows furrowed and their tongues clicking in disapproval. In working with Prof. Nichols throughout the year, long silences often took center stage as he contemplated some error in the code, an error I could not quite pinpoint with my novice eyes. Patience, I would think again, as the seconds ticked by excruciatingly slowly.

What I’ve learned is that if there’s one attribute science research demands, it’s patience. No matter if you are a novice or an expert, a student or a professor, machines will break, datasets will be confusing and coffee will run out. It’s dealing with these normal mishaps that makes a researcher resilient to adversity and all the more excited when all the pieces of a story fit together. But in my time working with Prof. Nichols, I learned that patience also demands admitting when there is a need for help. Why not seek advice, instead of mulling over a difficult problem alone?

Tianjia Liu CC’17 collects plant samples at Constitution Marsh. Photo: Jonathan Nichols

Tianjia Liu CC’17 collects plant samples at Constitution Marsh. Photo: Jonathan Nichols

In mid-April, after hitting a research roadblock, Prof. Nichols and I met with Allegra LeGrande, adjunct associate research scientist in the Center for Climate Systems Research and a NASA GISS physical research scientist, to discuss a particular GISS climate model that we had been applying to our project. In the corner of the Hungarian Pastry Shop, with coffee, hot apple cider and tiramisu in front of us, I marveled as ideas bounced back and forth. In the end, we left with many new things to think about and another more refined and reliable model that might possibly be the key to unraveling our problems.

As the Spring 2015 semester came to a close, my research project, a multi-proxy approach to reconstructing North Pacific wind conditions, had been in process for more than a year. In early April, not long before we met with Prof. LeGrande, Prof. Nichols had suggested that I submit a proposal to receive Lamont Climate Center funding for a project of my own design. In late-April, in my quest for a research topic, I stumbled across fatty alcohols, whose uses as a viable proxy to measure climate change are fertile ground for scientific study, unlike n-alkanes, another proxy I worked with last summer, whose uses are well established. Because organic compounds, such as fatty alcohols and n-alkanes, can be extracted from leaf waxes preserved up to thousands of years in sediment accumulating in wetlands, they can reflect past vegetation and climate changes. Knowing this, I decided to investigate how fatty alcohols can be used to measure temperature changes and, by extension, to more accurately model and evaluate global warming induced by human activities. About a month after I submitted my proposal, I was awarded funding and, as of Summer 2015, I am working on my project from scratch, including fieldwork in the Catskills.

Additionally, I started studying microfossils in deep-sea sediments with paleoceanographer Jerry McManus, professor of earth and environmental sciences, who I met as a result of my participation in the Fall 2014 Earth Institute Research Assistantship program. My ongoing project focuses on the biological pump, in which atmospheric carbon dioxide is used by surface-dwelling photosynthetic marine organisms for energy, thus introducing carbon into the surface ocean and subsequently storing it in the deep ocean. We want to understand how the strength of the biological pump changes with interglacials and glacials, or the Earth’s natural, approximately 120,000-year cycles between warmer and cooler “ice age” periods. As I look back on one year of research at Lamont, I realize that researchers are storytellers, their projects like stories yearning to be told. In the next year, I simply hope to weave my projects into stories and then polish them into scientific articles or blog posts.

Throughout the past year, many people have commented on the length of the commute I undertook on Fridays during the school year and that I will be taking every weekday this summer to conduct my research, but I answer that I don’t mind the trip to Lamont. I crave it. Every time I cross the George Washington Bridge via shuttle to the Palisades, I leave behind the city’s rowdy tension and enter the serene backdrop of whispering trees outside my lab. Lamont is more than a research haven. It is my meditative retreat to unwind and reset, to think and to push my limits.

Tianjia Liu CC’17 is an environmental science major. Aside from working on her research projects at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, she performs with Columbia University Lion Dance, co-manages the Columbia Science Review blog, writes poetry and enjoys learning Russian.