Isamu Noguchi CC 1926 was “the preeminent American sculptor.”

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Isamu Noguchi CC 1926 was “the preeminent American sculptor.”

Noguchi, circa 1970, fused Asian aesthetics with Western modernism in a career spanning six decades.

WALTER REISER / © THE ISAMU NOGUCHI FOUNDATION AND GARDEN MUSEUM, NEW YORK / ARS

Born in Los Angeles to a Japanese father and an American mother, Noguchi apprenticed as a teenager with Gutzon Borglum, the creator of Mount Rushmore. Borglum told him that he would never be an artist, but Noguchi’s mother disagreed, advising: “Be your own god and your own star.” At the College he enrolled as a premed but only lasted a year and a half. His mind was elsewhere; his chemistry and biology notebook, said his mother, was filled with “nothing but sketches of vagaries — fishes, rabbits, nude ladies, etc. Not one word of any science.” In spring 1924 a visit to Onorio Ruotolo, director of the Leonardo da Vinci Art School on East 10th Street, paid off ; Noguchi became his studio assistant, and his first exhibition, of 22 plasters and terra-cottas, came just three months after they met. Ruotolo proclaimed him a “new Michelangelo.”

Foot Tree (1928)

© THE ISAMU NOGUCHI FOUNDATION AND GARDEN MUSEUM, NEW YORK / ARS

Noguchi’s East-West duality informed his life and his work. Though American by birth, he spent a decade of his childhood in Japan, returning home in 1918; during WWII, he voluntarily spent several months in a Japanese-American internment camp in Arizona to better understand his own nature. “With my double nationality and double upbringing, where was my home?” he wondered. “Where my affections? Where my identity? Japan or America, both — or the world?” Noguchi ultimately determined that “For one with a background like myself the question of identity is very uncertain. It’s only in art that it was ever possible for me to find any identity at all.”

His output, he said, resulted from the “process of listening.” Always, his goal was to form and convey a relationship with his raw materials, tapping and releasing the natural forces that he felt within them. Indeed, Noguchi often thought of his creations as living things, asking to be fully awakened. “When I face natural stones, they start talking to me,” he said. “Once I hear their voices, I give them just a bit of a hand.”

Noguchi, wrote his biographer Hayden Herrera, preferred “certain shapes — columns, twisting pylons, pyramids and triangles, interlocking elements, cubes, circles, spheres, and emerging earth forms.” He expressed these forms with everything from soft marble to hard granite, from organic balsa to inorganic aluminum. In 1978, reviewing the traveling exhibition Noguchi’s Imaginary Landscapes, future Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Allan Temko ’47 wrote that Noguchi’s output sprang from his “several distinct selves, all exquisitely refined.”

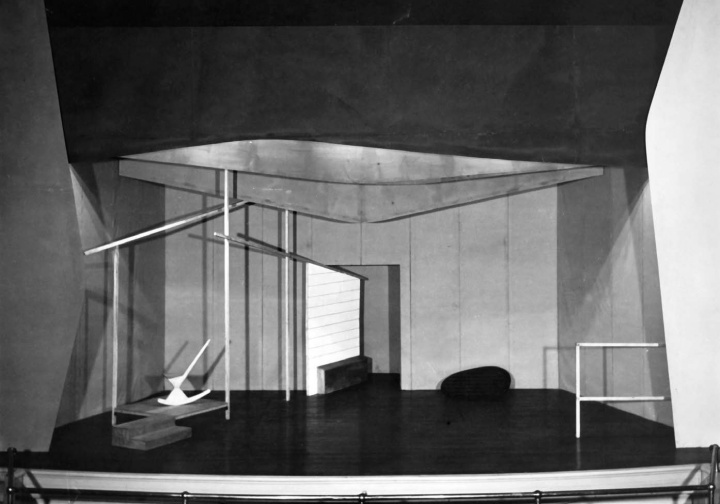

Ballet set for Appalachian Spring (1944)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, MUSIC DIVISION

Red Cube (1968)

Some time before he died on December 30, 1988, Noguchi had announced, “I have come to no conclusions, no beginnings, no endings.” Then again, such uncertainty defined his oeuvre. Sculpture, Noguchi said, “is the art which can only be appreciated in the raw, relative to man’s motion, to time’s passage, and to its constantly changing situation.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu