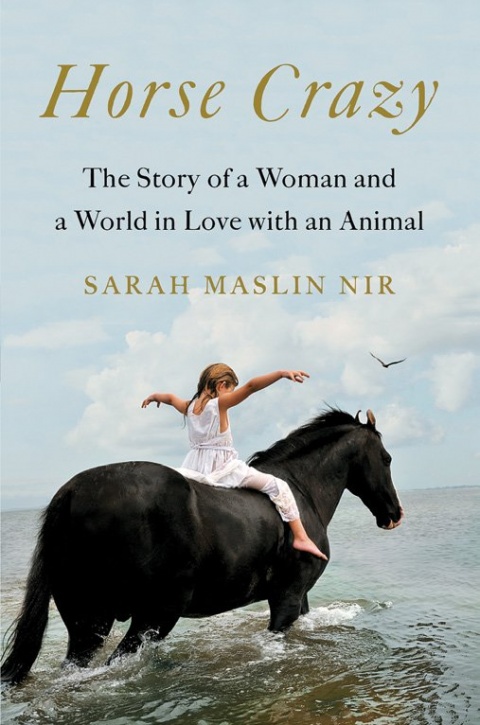

Sarah Maslin Nir ’08, JRN’10 has published an ambitious and highly personal debut, Horse Crazy: The Story of a Woman and a World in Love with an Animal

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Sarah Maslin Nir ’08, JRN’10 has published an ambitious and highly personal debut, Horse Crazy: The Story of a Woman and a World in Love with an Animal

ERIN O’LEARY

Now Nir has published an ambitious and highly personal debut, Horse Crazy: The Story of a Woman and a World in Love with an Animal (Simon & Schuster, $28). Nir is a committed equestrian, and her memoir makes clear how much the sport has shaped her. The book won advance praise from celebs and writers like Alec Baldwin and Susan Orlean, and was singled out as one of USA Today’s “20 Summer Books You Won’t Want to Miss.”

Horse Crazy is both self-exploration and survey, at once an odyssey through Nir’s own horse-obsessed life and a reporter’s look at the sometimes-zany world of horse fanatics. The child of a Holocaust survivor turned prominent psychiatrist, Yehuda Nir, and his psychologist wife, Bonnie Maslin, Nir had the toniest of Upper East Side childhoods. She attended a blue-chip school (Brearley) and summered in the Hamptons. But her cushy lifestyle wasn’t always a comfortable fit — Nir was all fidgety energy; to her older parents, immersed in high-profile careers, this was definitely a problem. They decided to solve Nir’s restlessness with horses. She writes: “Putting me on a moving horse would be the secret to getting me to sit still. ... On a horse, I could be as hyper as I itched to be but unable to skitter out of sight. ... They had no idea what their clever plan would set in motion.”

As Nir and her parents found out, horses are challenging beasts to love and ride: Pain is part of the deal. Nir’s story of her first bold cantering atop a towering horse is also the story of her first fall, an accident that narrowly missed being fatal. She learns to control the animals — and excel at equestrianship; Nir trains at the prestigious Claremont Riding Academy, works in tack shops and competes in shows as a teenager. At 17, just six weeks after breaking three vertebrae in her back (and being told she could no longer ride), she is back in the saddle at the Hampton Classic, clearing jumps and finishing second in her 60-person event. “To fall off is to ride,” she writes, and adds: “Perpetual pain is part of my life.” A reader can’t help but feel that her childhood rides were an early education in daring — preparation for the courageous journalism that has become her trademark.

As well as providing what her psychiatrist father might have approvingly called a sense of mastery, riding also gave Nir the emotional sustenance she needed as a child. In the moving chapter “Benediction,” she admits that she became closer to horses because she couldn’t be close to her three much-older brothers. “In the barn, I was grateful to be in the company of creatures who, unlike my family, had nowhere else to be but by my side,” she writes.

Nir understands that many riders feel as deeply about horses as she does, and part of her book revolves around her fellow fans and the horses that have captivated them. She visits a crowded competition in Leesport, Pa.; details the wild-pony colony on Assateague Island, Md.; and, most movingly, sidetracks into a little-known part of American history, via the Museum of the Black Cowboy. Nir makes the point that horses are a key part of our country’s ongoing story — “furls of an American flag in equid form, imbued with our narratives of national identity. They carry on their backs the tales we tell ourselves about who we are.”

What’s next for the adventurous Nir? After a rotation for the Times in West Africa, writing about terrorism in Benin, she is hoping to work as a foreign correspondent, something she tells CCT she was “born to do.” And does she dream of owning a stable filled with horses? Her answer is mischievous: “I have a fantasy of breeding a polka-dot horse and competing among all the glossy fancy horses in the Hamptons one day,” Nir writes. “Its name will be ‘Outrageous!’”

“W

My ears pricked. Even at that age I understood and loathed that my entrée into the sport was as an outsider. Everything about me was, a way of being in the world inculcated into me by family lore, by the narratives that tethered and constricted like sinews running taut through my life.

Externally, I appeared every bit part of the life my parents had devised for me, but that never occurred to me for the long years of my youth. I felt like an interloper, a spy, in my elite private school, Brearley, where it seemed I was the only one out of the 656 girls who brought kosher lunch meat on field trips and asked in the cafeteria if the soup contained pork. I felt like an outsider even as my address was 1050 Park Avenue because my mother was born out of wedlock, illegitimate issue of an illicit rendezvous of an Irish nurse and a Jewish doctor. She was abandoned by them, given up for adoption to my grandpa and grandma. Grandpa David and Grandma Frieda, the offspring of immigrant Russian Jews found themselves the instant parents of a green-eyed, flaxen-haired babe. Her narrative of abandonment, of being a stranger in a strange land, interlaced with my own.

But mostly it was because even in my plush life, it felt like we were still in hiding, so crisply is trauma transmitted through generations. My father’s early experience of being concealed in plain sight from the Nazis somehow felt to me that it continued on Park Avenue. I hoped our lavish address was the ultimate armor. Who could rip us from our lives again when we presided over the turret of the castle of the world?

Sometimes I woke up nights in my room in the back of the kitchen, worried the Gestapo — a word I had so often overheard while playing with plastic horses under the dining room table that to me it just meant boogeyman — had come. Other times I was afraid to explain to the blonde and barretted competitors in the short-stirrup, or kiddie, arena that I had been absent from a competition because it fell on Yom Kippur. I had muddled in my baby mind that their Aryan phenotype meant they were actual Nazis. There is a joke in my family that you can’t have a meal finish without someone mentioning the Holocaust: sometimes when no one has brought it up yet and dessert is scraped clean, someone will yell “Holocaust!” and we will laugh and push out our chairs and leave the table.

Looking back, it’s not very funny.

I felt like an outsider because my dad was old and didn’t know the rules of baseball. He was emphatically a foreigner. When he moved to America, he arrived at his first Fourth of July party dressed in a tuxedo because he had assumed that the celebration of the birth of the nation was an occasion that called for formal wear. And where American dads watched baseball, my father’s spectator sport was opera.

Second only to his love of Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, and Georges Bizet was his love of bragging about how little he paid for a seat to hear opera. He’d go solo to Lincoln Center most weeknights in New York’s winter. There, he’d hang out by the dancing fountain at the center of the plaza and try to spot the lovelorn — those who’d been stood up by opera dates and had a ticket to sell. He would approach them only minutes before the curtain rose. The seller would suggest $100; my father would hold up a crumpled $20. A few moments later, Dad would usually be snug (and smug) in the front-row velvet by the time the orchestra raised their quivering bows.

My father’s favorite aria is from Verdi’s Aida: “Ritorna Vincitor.” Return of the victor. Dad viewed his successful life as a magnificent victory lap, but I viewed it as tenuous. The success my parents had both amassed, despite their brutal beginnings, was not truly ours, I felt. It all seemed contingent, ephemeral, and liable to vanish. Just like my father’s bourgeoisie life had when the Nazis invaded and murdered my grandpa. Just like my mother’s biological parents had themselves vanished. How could I possibly belong to my family’s new life?

I think about why I chose horses to devote my life to, and I think of the soft muzzles and limpid eyes and thrumming heartbeats that so draw me to these animals. But trained by my Freudian father, I can’t help but think harder and unpack all of what equestrian sport represents in my society. It is the sport of kings and Kennedys, a pursuit dripping with elitism and Americana. As the progeny of immigrants, of people who did not belong to this land, I was claiming rights to the leisure of the Other. “Ralph Lauren was born a Jewish boychick from the Bronx named Ralphie Lifshitz!” my dad would tell anyone who would listen, and indeed it is true. Ralph understood my need to take cover, to escape the shtetl, or Jewish ghetto, for the safety of the ubermensch, to camouflage in their cashmere and jodhpurs.

So when Dad casually tossed out the fact that our family were horse people that summer day, my heart leaped. Dad had a string of catchwords and phrases he used ad infinitum, both in conversation and in his practice where he treated both Upper East Side elites and Jews from my city’s own shtetls: Crown Heights, Borough Park, and Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Because he was a polyglot, he was sought after by the city’s ultraorthodox, the Hasidic Jews who live in those insular enclaves where Yiddish is the vernacular, to treat them in the languages they spoke. He saw them largely for free, palming the poorest of them subway fare to flee their ghettos of Brooklyn for his office down the street from our apartment at 903 Park Avenue. Under their head-coverings, fur shtreimels for the men and sheitels, wigs worn for modesty to hide women’s own hair, was strife — just like any other New Yorker. Often it was underscored and exacerbated by the repression demanded by extreme religious observance.

For them, Dad offered his favorite diagnoses-by-catchphrase. One was “A sense of mastery.” What we were all looking for, Dad said, was the feeling that we achieve only by mastering something, and he exhorted his patients and me to take full command of our lives. Those endemically human feelings of being lost, rudderless, unmoored, Dad believed, are the result of not giving oneself permission to seek out mastery. Fully living was not just making one’s place in the world, he said, but mastering it.

“Belonging and not belonging” was another favorite — a paradox that he believed was the root of so many of his patients’ suffering. For the largely impoverished Hasids, belonging and not belonging was the struggle of remaining pious anachronisms in a modernizing society. In his own daughter, belonging and not belonging was inescapable as well. It was why my mother had torn up the wiring on the grandiose toe buzzer beneath the dining room table in the Park Avenue apartment. She was in the apartment but not of it, her actions insisted.

I experienced it as an essential tremor of unworthiness, an electric current that pulsed one word like neon behind my eyes: outsider.

From the book HORSE CRAZY: The Story of a Woman and a World in Love with an Animal by Sarah Maslin Nir. Copyright © 2020 by Sarah Maslin Nir. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu