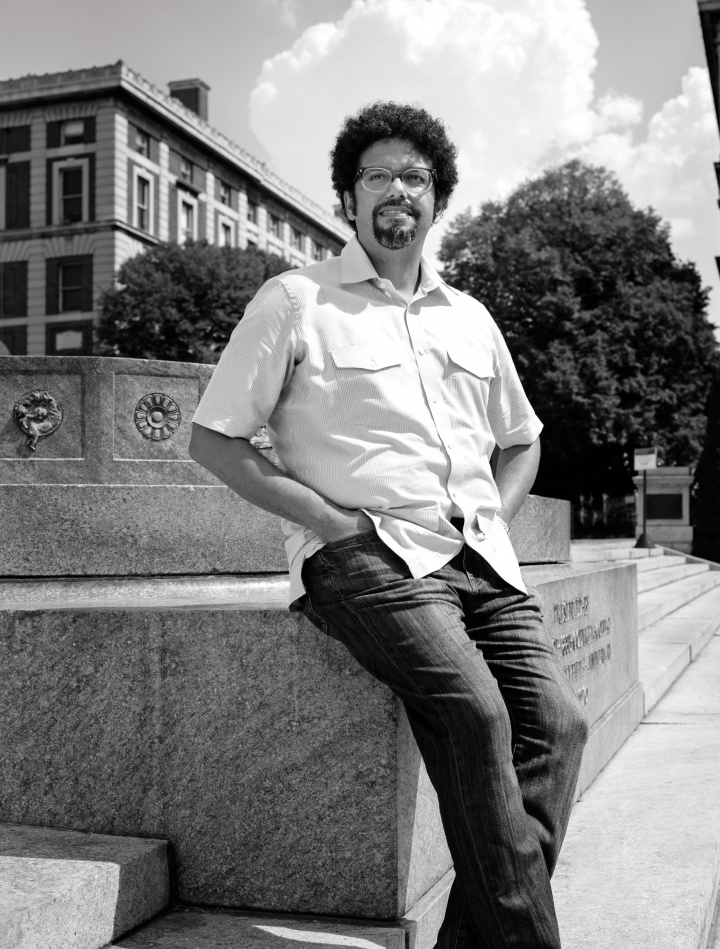

Associate Professor Frank A. Guridy feels

“a real responsibility” to bettering the

College community.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Associate Professor Frank A. Guridy feels

“a real responsibility” to bettering the

College community.

Frank A. Guridy never saw himself becoming a professor. Born working-class in Inwood — “a stone’s throw from Baker Field” — and raised in the Bronx, he was in fact the first person in his family to go to college. After graduating from Syracuse in 1993, Guridy, an associate professor of history and African-American studies, completed his Ph.D. at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in 2002. He taught at the University of Texas, Austin, for 12 years before starting at the College in 2016.

Jörg Meyer

Now he has the opportunity to mentor students who want to follow in his footsteps. This fall, Guridy began a three-year term as the faculty coordinator for The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship program, a Mellon Foundation initiative to put more underrepresented minority students on the path to earn Ph.D.s and prepare them for academic careers. Guridy will lead weekly seminars, advise MMUF fellows, and help candidates identify and explore topics that pique their intellectual interests.

As a historian, Guridy has an intellectual interest in the institution itself. In fall 2017, he began teaching “Columbia 1968,” a class that asks students to deeply examine one of the most important events in the University’s history. And though his current research has shifted to U.S. sport and urban history, focusing on the relationship of sports to urban political economies, there is still a College connection: “My dad used to watch the Columbia football games, so my first relationship with and awareness of Columbia is connected to sports,” he says.

In 2010, Guridy published his award-winning first book, Forging Diaspora: Afro-Cubans and African-Americans in a World of Empire and Jim Crow, about the connections between the black freedom movements in Cuba and the civil rights movement in the United States during the first half of the 20th century. He took an eight-month sabbatical this year to complete his next book, an examination of Texas’ impact on American sporting culture. Guridy returned to his office one late afternoon in July to speak with Columbia College Today.

Q: How did you become interested in studying history?

A: I was a political science major at Syracuse at an interesting time, the period of the first Gulf War in 1990. One of my professors was an international political economist and I got sucked into the history of British imperialism in India and the Middle East.

When I was a junior I got a letter saying there were opportunities for underrepresented students to get their Ph.D.s, and even though I had never considered grad school, I became convinced I had the makeup to go. I got into Northwestern’s political science master’s program, moved to Chicago and then in the summer before I was to begin my first semester, I realized the program wasn’t the right fit for me. I took a year off and worked odd jobs while I figured out my next move. I spent a lot of time in the city’s amazing bookstores, and that helped me realize that studying history was the better fit. I got my master’s from the University of Illinois before transferring to Michigan to do my Ph.D. work.

I was very interested in studying the history of the Caribbean, since my family is from there. I had the good fortune of going to Cuba to do research and I ended up regularly traveling and researching on the island from 1998 to 2009.

Q: What was that like?

A: It was challenging — this was before the agreements between the Obama administration and Raúl Castro, before the normalization of U.S. and Cuba relations. You had to get a license from the U.S. Treasury Department and then travel through a third country. Once I got there I needed to get permission to do research, and they were suspicious of foreign researchers. So I had to learn how to make the right connections, convince them I wasn’t there to overthrow the Cuban government. [Laughs.] They didn’t know what to make of me, but I felt very comfortable there.

Q: And Forging Diaspora is based on your work there.

A: Yes. When I was there it became clear to me that Cuba was totally intertwined with the U.S. in the pre-Castro era — essentially, Cuba was sort of a neo-colony of the U.S. One of the results of that relationship was a flourishing of all these interesting cultural and social relationships between African-Americans and Afro-Cubans — between artists, between intellectuals, there was a lot of synergy that people had not really known about. And so my book became about how these two black populations of different backgrounds would have these perceived commonalities and how they used each other as a way to inspire their own freedom movements in their own homelands.

I think it behooves us to look at an earlier period of political polarization

and to see if there are any lessons that can be learned.

Q: What made you start the “Columbia 1968” class?

A: I was inspired by the “Columbia and Slavery” course that President [Lee C.] Bollinger helped initiate, which encourages students to look at Columbia’s relationship to slavery, but it really is this bigger project of looking at this institution’s history. They had this amazing event at Low Library; I saw the students talk about their research and a light went on in my head. The anniversary of the protests was coming up, and I wanted to do a class that was just about the events of ’68 and have students research any aspect of it. I thought that undergraduates could handle the challenge of doing work on a politically polarizing topic, in a period that’s fairly recent, and contend with people who are still alive. Students wrote papers about the causes, the aftermath, the protest itself, the experiences of women at Barnard, the Asian-American student experience, the Jewish student experience, the Harlem aspect — there are so many different ways to look at it.

Q: In a New York Times article published earlier this year about the Spring ’68 anniversary, you said: “They should put a plaque on the Sundial. It should say, ‘This event happened. It was difficult and violent. But it made our community a better place.’” In what ways do you think the College community is better?

A: It became a more inclusive place. From the black student perspective, Columbia became a better place. A year after the protests, Charles V. Hamilton — the renowned political scientist who co-wrote Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, which was a bible for black student movements at the time — was hired. Hollis Lynch was hired as the first black tenured professor in the history department. There are the beginnings of a curriculum of black studies. There are bumps in the road all the way through, but in terms of black students having a space socially and intellectually, that’s all super important.

Then there’s greater representation of groups on campus: With the development of the University Senate, and students having a say in how things are run, it became — at least in theory — a more democratic place. Spaces were created that did not exist before and the administration understood it had to be more responsive to key parts of its constituency. It forced Columbia to join the late 20th century, and to me that’s a good thing. That’s the story of many institutions — you don’t have change without struggle.

Guridy in Cuba, in 1998.

Courtesy Frank A. Guridy

Q: What do you think about teaching the course again this year? Do you feel like you’re bringing something different to it in 2018 than in 2017?

A: I think in some ways it’s a continuation. Of course, the 2016 election was in my head when I first thought about this class, but that wasn’t the only thing. I am a scholar who is committed to political and social change. So that means my work as a teacher is about getting students to think in a broader and more critical way about the world they live in.

Q: And that’s a tenet of the Core.

A: Yes, and I take that seriously. We’re living in a very polarizing moment, and I think it behooves us to look at an earlier period of political polarization and to see if there are any lessons that can be learned — not that they can be replicated, but it absolutely requires a reckoning with the legacies of that period and how they continue with us today. And I think our students are hungry for that. I think a lot of them are probably scared, and they need to know about people who have been here before — not just the protestors, but also a whole cast of characters who were, in their own way, trying to make Columbia a better place, and make the world a better place.

It sounds really idealistic but I think it’s important to encounter historical actors like that. Not to do the same things they did, but to see that in the past there were people who were facing difficult circumstances who felt a sense of agency in tackling those challenges. I think our students intuitively understand that after 2016. It’s time for us to think about how we can make our country better and our world better than what we have right now. And that’s why this class works.

Q: Speaking of the Core, have you taught any Core classes?

A: I haven’t, but I would be interested down the road. I feel like I’m missing out on a key part of the Columbia experience by not teaching CC. The most impressive people I’ve met at Columbia are the undergrads. Columbia is like a liberal arts institution insofar that students expect you to give them time, but not in an entitled way. The vast majority of my interactions with undergrads are not about grades; they just want to talk about ideas.

Q: What do you think is important about liberal arts education right now?

A: I think it encourages students to engage in the act of imagination. It forces them to think creatively about their career goals, to not get locked into a pre-professional path. Along the way they’re encountering classes from the Core to seminars in whatever department they’re in, thinking creatively about knowledge production and how they can translate that knowledge to the broader world. And because it’s liberal arts in New York, they can walk down the street and be able to imagine all sorts of application possibilities.

Q: Are you teaching any classes about sports culture?

A: Yes, I teach a big lecture class called “Sports & Society in the Americas.” It gets students to think about sports as a site of critical inquiry. If you want to understand how we think about manhood, womanhood, race, patriotism — sport is a fascinating way to think about these questions. I’m going to teach it again in fall 2019. I love it, and I get a lot of non-history majors and a lot of student-athletes. It gives these really smart young people permission to think about a passion they have and consider it as an intellectual exercise.

Q: And your upcoming book is about sports in Texas?

A: Yes. Texas has an interesting relationship to the popularization of sports in the U.S. in the 20th century, and also its social and cultural impact. Football emerged in the Northeast, but its popularity in southern states like Texas made it a national phenomenon. The building of the Houston Astrodome in 1965 set the template for all stadium construction afterward — they developed from structures with uncomfortable bleachers where people went solely to watch sports to these hyper-privatized, living room/man caves with giant scoreboards and luxury boxes. Stadiums become places that generate revenue. Houston also plays an interesting role in the feminist and civil rights movements, as a place where talented female and black athletes began emerging on the national stage. The famous “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs, for example, happened in the Astrodome.

Q: Sounds like you had a productive sabbatical. What do you like most about teaching here?

A: This place allows me to do all the things I want to do. It allows me to teach undergraduates, to train scholars, it allows for an intensity of intellectual interaction. Plus there’s a lot of institutional work for me to do here — as diverse and international and inclusive as Columbia is, it still needs more diversity in positions of power, and as a scholar of color who’s tenured at the University I feel a real responsibility to that. It’s part of the reason I’m going to work on the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program, to encourage underrepresented students to get Ph.D.s in the humanities.

Q: You’ve come full circle!

A: Yes! I was raised in a working-class family in the Bronx! This is a wonderful opportunity to continue the work I want to do in my hometown. There’s an amazing energy that runs through this community, and I see myself being fed by it for quite some time.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu